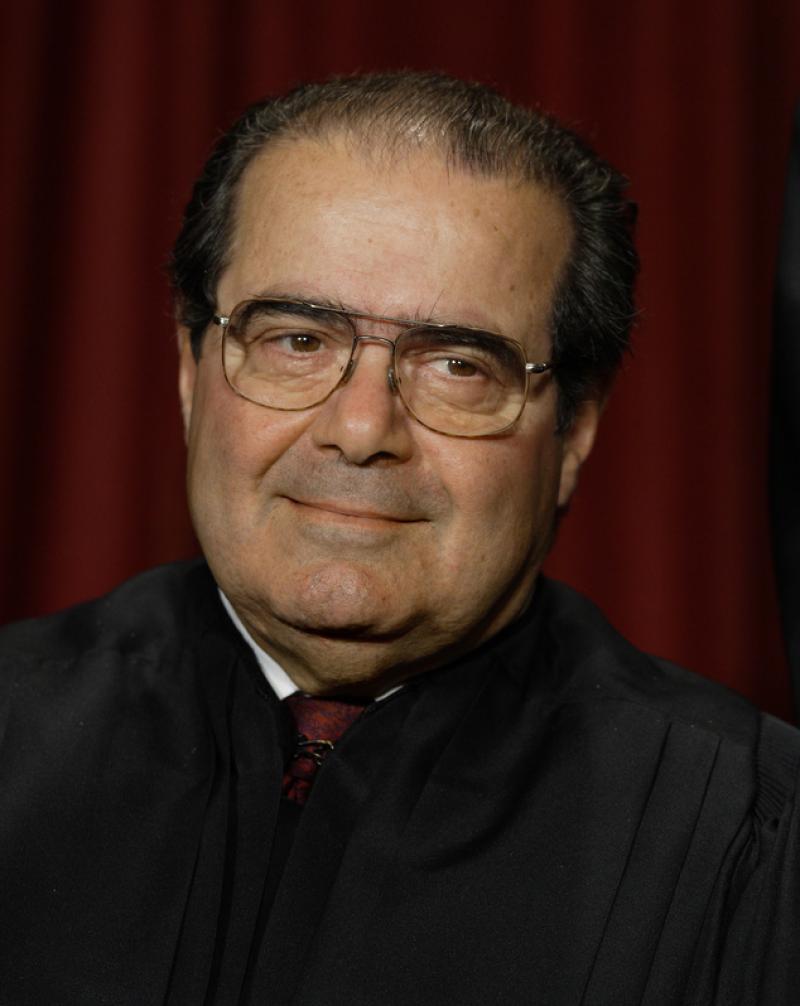

'The Essential Scalia' Review: What RBG Admired

By: Paul Clement (WSJ)

In the days since her passing, much has been said about the cross-aisle friendship between Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Antonin Scalia, who passed away four years and one presidential election cycle earlier. Their relationship was warm, genuine and enduring, spanning almost four decades. It was not a union of convenience or a strategic partnership. Justice Ginsburg did not share operatic vignettes or her husband Marty’s cooking with Justice Scalia in an effort to cajole a vote or moderate his jurisprudential views. They were true friends notwithstanding profound disagreements on the issues they each cared about most passionately.

What then explains their deep bond? “The Essential Scalia,” a collection of the justice’s opinions and speeches edited by Judge Jeffrey Sutton and Edward Whelan, supplies some answers.

Start with the book’s cover photograph. Two things are striking. First, it harks back to the days when bringing a smoking implement to a formal photo shoot was apparently de rigueur. But the critical feature is not the pipe but that smile. The young government lawyer looks like the happiest man alive. Either he is laughing at a very good joke or he cannot believe his good fortune in being paid to study and solve tricky legal questions. Ginsburg loved his sense of humor. While others had trouble getting a smile out of her, Scalia said his only problem was getting her to stop laughing.

The next clue comes in the foreword, written by Justice Elena Kagan. Here is another liberal legal lioness revealing both her deep admiration and her genuine fondness for Scalia. What is it about this man? Justices Ginsburg, Kagan and Scalia all thought long and hard about legal issues and pored over drafts of their judicial opinions. They all worked to get the phrasing and the grammar just so.

The two liberal justices could not help noticing that Scalia was a legal stylist without peer, and they admired his excellence in their shared pursuit. As Justice Kagan puts it: “No one has ever written quite like Nino, and no one ever will.” But it was never style “for the sake of style: it was always in service of ideas.” When he wrote that a legal test was akin to asking “whether a particular line is longer than a particular rock is heavy,” he had a point, and the test never fully recovered. When he wrote that Congress does not “hide elephants in mouseholes,” he colorfully captured a basic reality of legislative drafting—namely, that legislators do not alter the fundamental thrust of a law by tweaking ancillary provisions.

But the real explanation for the bond between Scalia and his philosophical adversaries lies in his career-long effort to demarcate the proper role for judges in our constitutional system. Whether they agreed or disagreed, judicial peers could not help admiring what he said on that subject—and of course how he said it.

The editors of “The Essential Scalia” have skillfully collected and excerpted Scalia’s judicial writings and a few speeches and articles, and the results are as readable today as they were when they first appeared. That is no mean feat. Many judicial opinions have a short shelf life. No matter how contentious or important a dispute was in its day, once it is resolved, the opinion resolving it may be forgettable. Not so with Scalia’s work; he was fascinated by the deeper questions raised by the case. What makes so many of his opinions worth reading and rereading is not what they say about a particular statute or constitutional dispute but what they say about statutory construction or constitutional interpretation in general.

Scalia could spin gold out of even the dullest dross. To pick two examples, he used an otherwise unimportant telecommunications dispute to hold forth on the proper role of dictionaries and their usefulness in statutory construction (spoiler alert: Webster’s Third does not fare well). He also used Casey Martin’s effort to use a cart in a PGA event to pen some of the most memorable lines in the long history of statutory construction and the longer history of golf.

The editors have included both majority and dissenting opinions, but the latter predominate. That is no accident. For most of his tenure, the center of the Supreme Court was to Scalia’s jurisprudential left. Despite the clarity and stylistic verve of his dissenting opinions in cases like Morrison v. Olson and Mistretta v. U.S.—concerning the independent counsel and sentencing guidelines, respectively—they failed to persuade his judicial colleagues. But the dissenting opinions merit their starring role in this volume for two reasons. First, they represent not just the essential Scalia but the undiluted Scalia. Unlike a majority opinion that must be tucked and trimmed to accommodate the views of other justices in the majority, a dissenting opinion, especially a solo dissent, captures the justice’s views without compromise or moderation.

Second, in his dissenting opinions Scalia was clearly playing a long game. When he realized he could not persuade his fellow justices, he did not give up and mail it in. Instead he redoubled his efforts to persuade and broadened his audience to include the future law students who would be assigned to read majority and dissenting opinions.

His charms reached well beyond the liberal jurists with whom he served. A generation of law students raised on Scalia opinions are now filling the ranks of the judiciary and other branches of government. One of them is the nominee to fill Ginsburg’s seat on the court, Amy Coney Barrett, and she has indicated that Scalia’s “philosophy is mine too.” The essence of that philosophy is concisely reflected in this volume. The book will be especially illuminating to anyone who wants to unlock the mystery of why Ginsburg admired Scalia—or who wants to get a sense of where the Supreme Court may be headed.

Mr. Clement, a former solicitor general of the United States, has argued more than 100 cases before the Supreme Court.

Tags

Who is online

53 visitors

As a Justice and as a man - he was a giant

The book is:

THE ESSENTIAL SCALIA

Edited by Jeffrey Sutton and Edward Whelan

Crown Forum, 334

He was indeed and the type of bi partisan working together and friendship he engaged in is sorely missed. I think that the article is right about Scalias influence among future lawyers and judges. I also think that ACB will emulate him in forming bi partisan friendships as well as his judicial philosophy when she joins the court in November.