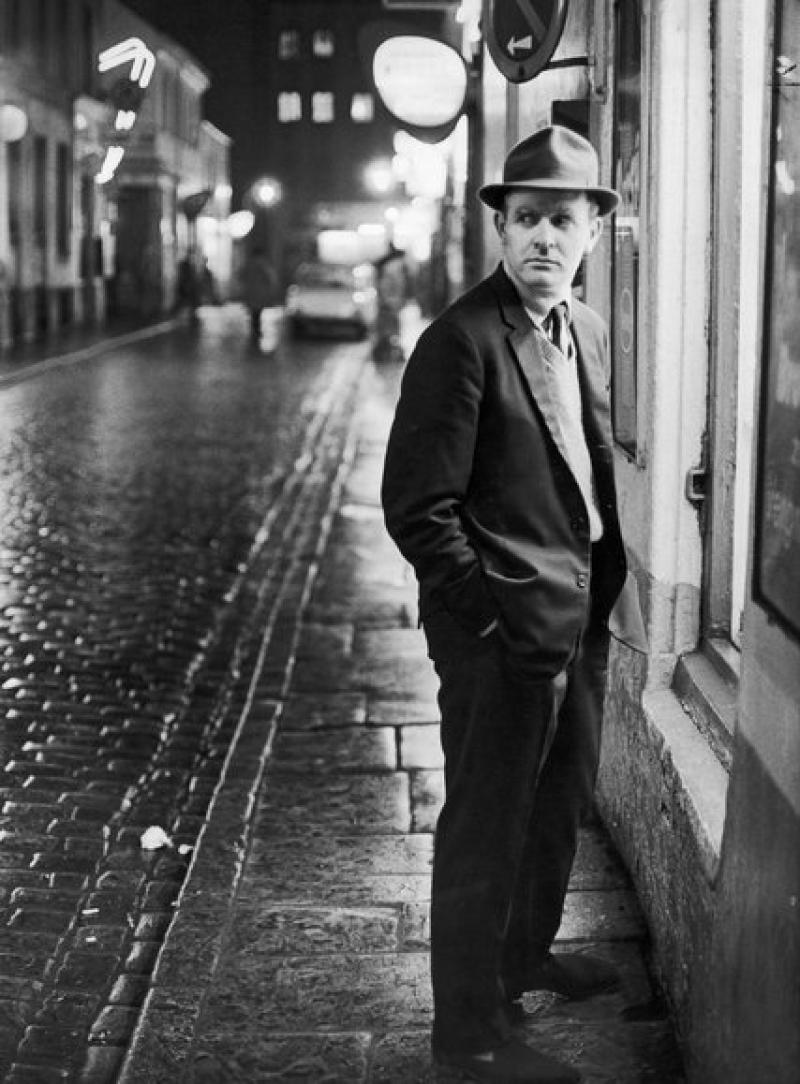

Appreciation: John le Carre, 1931-2020

By: Tom Nolan (WSJ)

The late John le Carre, born David John Moore Cornwell in 1931, liked to quote fellow English novelist Graham Greene to the effect that "childhood is the writer's bank balance." Thanks to an anxious upbringing, young David acquired enough authorial capital for the future le Carre to produce 26 books: tales of espionage and more that injected emotional complexity into "the secret world" and transformed spy fiction forever.

"The only relationship that I had as I grew up," le Carre told a Beverly Hills audience in 1999, "was with my father . . . a mercurial, enormously attractive and totally amoral person who was, by profession, not to put too fine an edge on it, a confidence trickster and saw the inside of a number of prisons in his lifetime. The effect of that continues to haunt me."

In his 2016 autobiographical collection "The Pigeon Tunnel," le Carre recalled how "Ronnie the conman could spin you a story out of the air, sketch in a character who did not exist, and paint a golden opportunity when there wasn't one." When not separating gullible partners from their funds, his father could also be violent and was so to his first and second wives. "Ronnie beat me up, too," le Carre wrote, "but only a few times and not with much conviction." David's abused mother (Ronnie's first wife) left when he was 5, and the boy would spend his youth poring over business papers that his father kept boxed in the attic, seeking details of his dad's larcenous schemes. "By the age of eight I was already a well-trained spy."

The Oxford-educated David made espionage his career, working first for MI5, then MI6. He wrote his first two works of fiction—under a pseudonym, for security reasons—while still in his government's employ. Starring in these books was an unprepossessing intelligence officer named George Smiley.

Le Carre wanted to up his literary game, partly, he claimed, in response to Ian Fleming's James Bond fantasies of the 1950s and '60s, which he dubbed "cultural pornography." "It was a very rum thing," he observed, "being in the secret world and watching the literary extension of it as a kind of saccharine vision of a life we didn't live. Anybody involved in it I think would have been aware of the human cost, the incompetence, the constant cockups, the tragicomedy of it all. . . . Espionage . . . needed some kind of serious treatment, I thought."

“The Spy Who Came in From the Cold,” published in 1963, was very serious and an enormous international success. Greene called it “the best spy novel I have ever read.” Featuring Smiley in a supporting role, this bleak chronicle of a British agent manipulated into a fatal East Berlin mission changed forever how readers perceived the real world of those who spy and are spied upon. Le Carré, who resigned from MI6 in 1964, was by now a literary household name, and he assiduously produced three more novels in the next eight years. But he felt he had lost his way as a writer—until he returned to the theme of betrayal, which had obsessed him since childhood.

Enlarging upon his own youthful deprivations, he set his sights on the traitors who had flitted across the Cold War stage. He began writing a story about a Kim Philby type; the resultant work, 1974’s “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy,” was the first of a trilogy (with “The Honourable Schoolboy” and “Smiley’s People”) that would become for many the pinnacle of modern espionage fiction.

In “Tinker Tailor,” Smiley came into his own as a full-fledged protagonist, called out of retirement to trap a still-active double agent—a “mole”—in the Secret Intelligence Service. Eventually Smiley does battle with the mole’s Soviet spymaster, Karla, his nemesis in the covert world. Partly because of a brilliant BBC adaptation of two of the books, Smiley and crew became popular-culture icons, and le Carré was hailed not only as a master of spy literature but the premier Cold War novelist.

More than a dozen more novels followed the “Karla” trilogy, among them “A Perfect Spy,” the work le Carré said he was most proud of, in which he at last came to fictional grips with the ghost of Ronnie Cornwell. “I hung around for the better part of 25 years,” he would recall, “trying to write about this impossible monster in my life—loveable monster, whatever—and every time I approached it, it became like a weepie, with this poor son being bullied and kicked around and so on by this wicked father. But the moment I made the son wicked, then everything came together.” This is the work that Philip Roth, in its publication year of 1986, called “the best English novel since the war.”

“A Legacy of Spies” in 2017 came as a special treat to the author’s long-time readers. Billed as “his first Smiley novel in more than twenty-five years” (Smiley last appeared in 1990’s “The Secret Pilgrim”), it shifted between a tense present and a decades-old past. Narrator Peter Guillam, Smiley’s trusted colleague and mentee, is called to account for his movements and motives throughout a career of covert ops.

Throughout the novel, well-known players in past le Carré works have their back stories updated. Hidden chapters are discovered and read into the record. Accepted knowledge is turned on its head. Le Carré thus reinterprets his classic Smiley saga in light of later events and subsequent paradoxes, allowing his hero’s generation (which included the author himself) a retrospective defense. “If I was heartless,” Smiley tells Guillam, “I was heartless for Europe. If I had an unattainable ideal, it was of leading Europe out of her darkness towards a new age of reason. I have it still.”

Tags

Who is online

46 visitors

He wrote with an exquisite use of the English language.

RIP John Le Carre.

I am not familiar with his works, but my late husband was. RIP Sir.

I've read all his books, he was ahead of his time regarding spy novels.