'The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics' Review: On Judicial Supremacy

By: WSJ

In the United Kingdom, there is a tradition of printing 100-page books—booklets, really—from lectures given by notable judges and lawyers. The Hamlyn Lecture series, for example, has featured such distinguished talks as Lord Denning's "Freedom Under the Law" (1949), Professor Arthur Goodhart's "English Law and the Moral Law" (1953) and Dean Erwin Griswold's "Law and Lawyers in the United States" (1964). The primers are collectible, memorable and quotable.

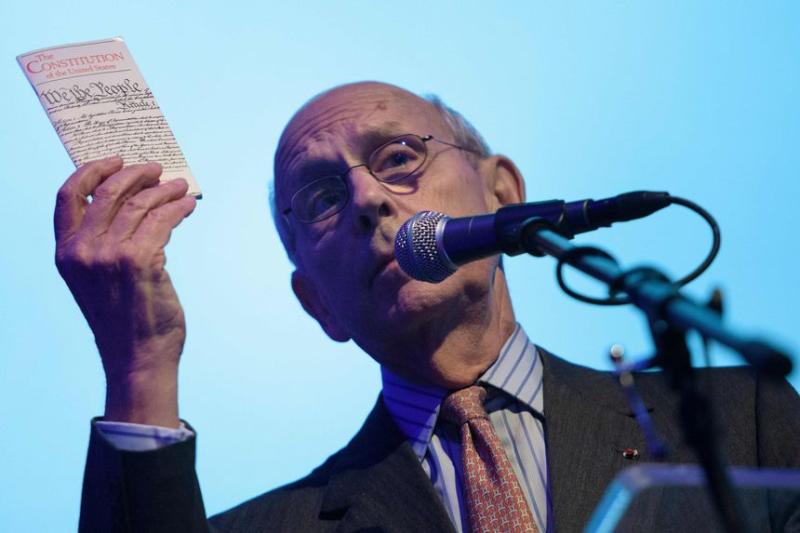

Now Harvard University Press has perhaps embarked on a similar plan for Harvard Law School's annual Scalia Lecture series, instituted in 2013. This year the program turned to Justice Stephen Breyer, who has thought deeply about judicial power, the rule of law and the role of the judiciary in the American polity. Perhaps these three subjects are in the nature of a trinity: three that make up one. In any event, their position in the U.S., when compared to the rest of the world, has been enviably secure. Yet insiders know that, here as elsewhere, the institution is perennially precarious.

In April Justice Breyer spoke from a lectern to a Zoom audience, and now his speech is preserved in book form. Those wishing to know Justice Breyer’s thoughts can choose either to read the book or to watch the two-hour speech on YouTube. You’d feel edified in doing either.

Quoting Cicero, Justice Breyer argues that the only way to ensure obedience to the Supreme Court’s pronouncements is to convince people that the Court deserves obedience because itsdecisions are just. That means an observer must assess not the justness of each individual decision, but the justness of the Court’s decisions collectively and in general.

In support of this thesis, Justice Breyer gives a mini-lecture on American constitutional history and on the struggle, when interpreting the Constitution, for judicial supremacy. He explains how Chief Justice John Marshall, in Marbury v. Madison (1803), decided the case in a most unexpected fashion—pleasing President Thomas Jefferson with the specific result but only by establishing the Court’s ability to declare acts of Congress unconstitutional. That all but guaranteed acceptance of the Court’s power, at least in that case, while establishing the doctrine of judicial review.

Nearly 30 years later, when the Supreme Court declared that the State of Georgia had no rightful control over Cherokee lands there—lands where gold had been discovered—President Andrew Jackson and the state of Georgia both ignored the decision. There was no enforcement. As a result, the Cherokee Nation was driven to Oklahoma on the infamous Trail of Tears.

After that outrage, adherence to the principle of judicial review was, reassuringly, mostly re-established. Yet even as late as the 1950s, with Brown v. Board of Education, it wasn’t at all clear whether the Court’s decision would be enforced by the Executive Branch. Some today may have forgotten that, to enforce Brown, President Eisenhower sent 1,000 parachutists from the 101st Airborne Division into Arkansas. Central High in Little Rock would no longer be white-only. In taking that bold action, Eisenhower ignored the advice of James Byrnes, the South Carolina governor who had once briefly served on the Supreme Court, before returning to the Roosevelt administration to aid the war effort. At the time of Brown, Byrnes advocated taking the Jacksonian stance of doing nothing to enforce the Court’s decree. The U.S., in other words, came perilously close to a 20th-century trail of tears—one that would have resulted from reducing the Brown decision to empty words on a piece of paper.

If the events of the past year have taught us anything, it’s that the established institutions of the United States are more fragile than almost any of us had previously thought. We used to believe, for example, that strongman coups were exclusively in the domain of Third World countries. Now we know that the potential is also here on our shores.

Meanwhile, judicial institutions are under attack once again. We can’t say “under attack as never before,” because Justice Breyer shows us that such attacks are a persistent problem. Although he abjures speaking directly about the current Court-packing proposals, the author wants to “ensure that those who debate these proposals also consider an important institutional point, namely how a proposed change would affect the rule of law itself.” His voice is a powerful one, and the brevity of this book, together with its readability, should ensure its lasting influence. Like anyone else, Washington leaders can absorb its message in a single evening.

Antonin Scalia, for whom the Harvard lecture was established—three years before his death—would doubtless applaud Justice Breyer’s message. The two justices discussed these issues at length, often publicly. They influenced each other and sharpened their viewpoints about the proper role of the judiciary in the Framers’ view and in the modern world. The primary disagreement between Scalia and Justice Breyer had to do with interpretation. Scalia thought that his colleague’s views would encourage the politicization of the courts.

The central question is whether courts should interpret legal documents by giving them a fair reading of what they denoted at the time of adoption, or whether courts can interpret those texts according to their broad purposes (not getting too caught up in grammar and historical dictionaries) and even the desirability of results. As Justice Breyer puts it: “Some judges place predominant weight upon text and precedent; others place greater weight on purposes and consequences.” As the popular mind conceives it, conservatives do the former, and liberals do the latter. And the latter approach, according to Scalia, leads inevitably to appointing judges who will vote for outcomes they personally favor. Hence the process becomes more politicized the further judges stray from the text.

Justice Breyer walks a tricky tightrope in arguing that it’s “wrong to think of the Court as a political institution.” Without quite solving that paradox, Justice Breyer has given us an important document on American civics. He knows that Americans must foster a sense of mutual trust, which requires both understanding and engagement. In his concluding words, he says that “we must undertake that work together.” As if on cue, our famously Anglophile author arrives at that line on page 100.

Mr. Garner is the editor in chief of Black’s Law Dictionary and the co-author, with Antonin Scalia, of “Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts.”

"The central question is whether courts should interpret legal documents by giving them a fair reading of what they denoted at the time of adoption, or whether courts can interpret those texts according to their broad purposes (not getting too caught up in grammar and historical dictionaries) and even the desirability of results. As Justice Breyer puts it: “Some judges place predominant weight upon text and precedent; others place greater weight on purposes and consequences.” As the popular mind conceives it, conservatives do the former, and liberals do the latter. And the latter approach, according to Scalia, leads inevitably to appointing judges who will vote for outcomes they personally favor. Hence the process becomes more politicized the further judges stray from the text."

That is the question and has been since Roe v Wade.

Another question involves the lower courts: Should Federal judges be allowed to impose national injunctions, which are not based on precedent nor text nor order nor SCOTUS decisions but on gaining some sort of desired result?

The book is

The Authority of the Court

By Stephen Breyer

Looks like a good read, i'm picking it up.