Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020 | Prison Policy Initiative

By: Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner (PrisonPolicy)

Report showing the number of people who are locked up in different types of facilities and why - 2020

Yesterday, I seeded a map about the US prison population, that drew quite a few questions.

This should answer almost everything ...

Can it really be true that most people in jail are being held before trial? And how much of mass incarceration is a result of the war on drugs? These questions are harder to answer than you might think, because our country's systems of confinement are so fragmented. The various government agencies involved in the justice system collect a lot of critical data, but it is not designed to help policymakers or the public understand what's going on. As public support for criminal justice reform continues to build, however, it's more important than ever that we get the facts straight and understand the big picture .

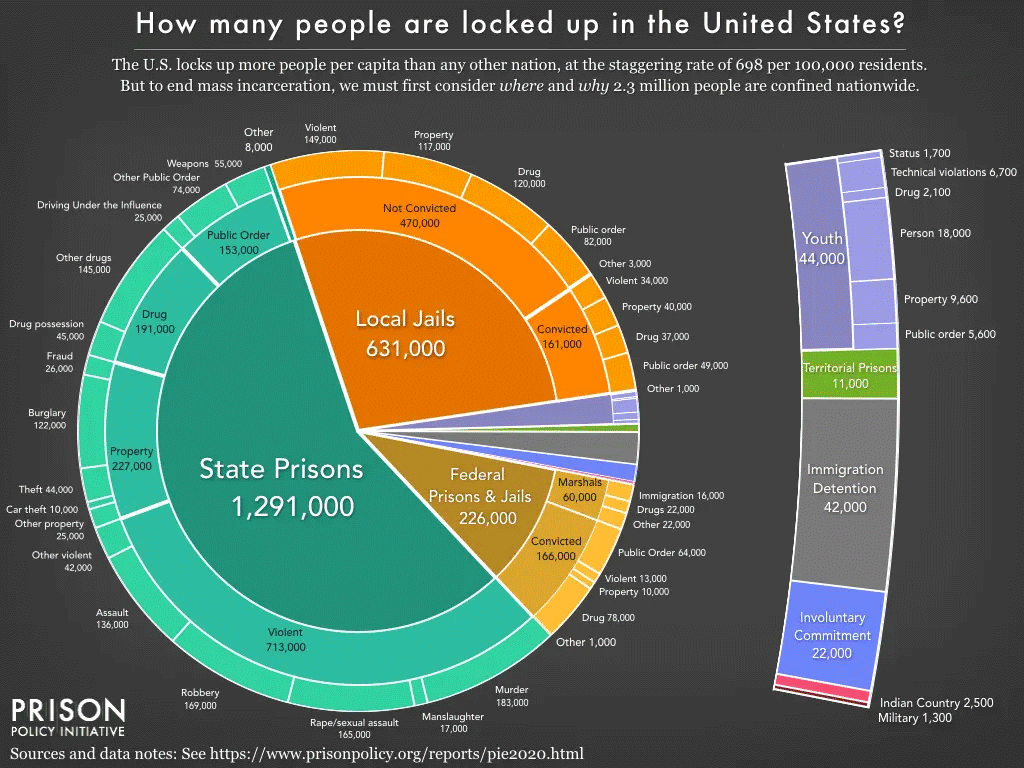

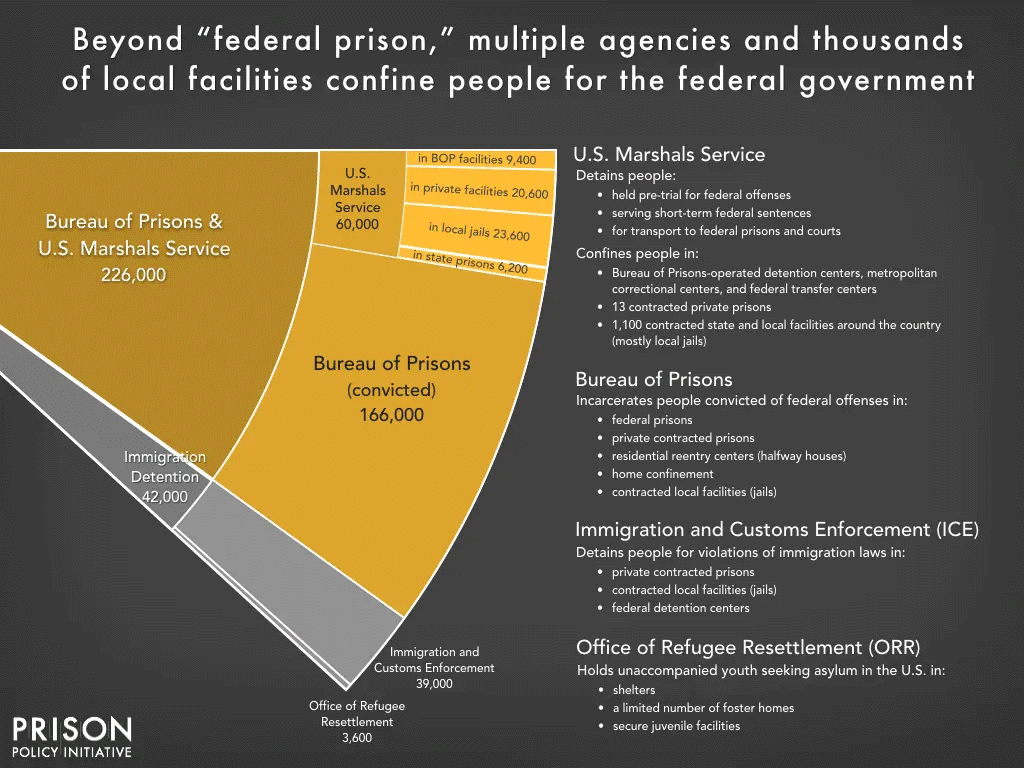

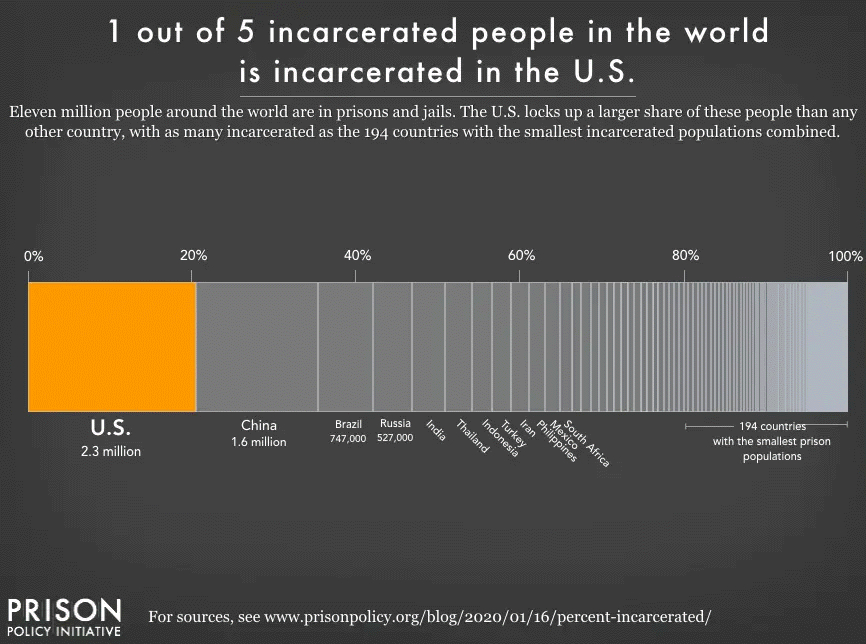

This report offers some much needed clarity by piecing together this country's disparate systems of confinement . The American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories. 1 This report provides a detailed look at where and why people are locked up in the U.S., and dispels some modern myths to focus attention on the real drivers of mass incarceration, including exceedingly punitive responses to even the most minor offenses.

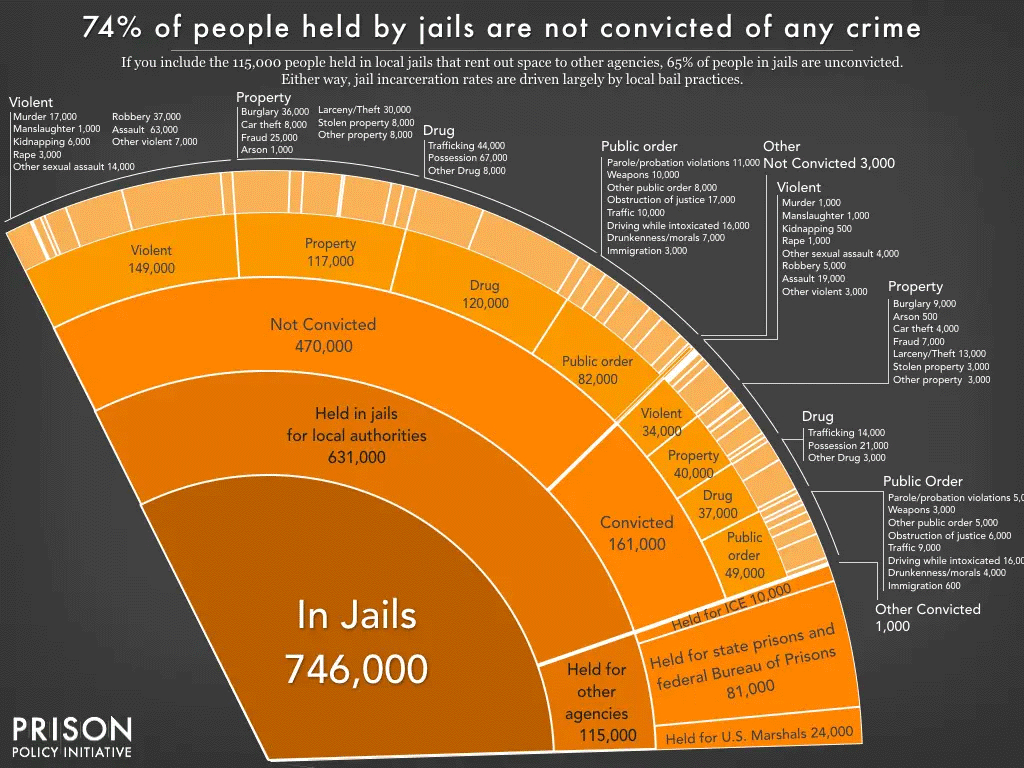

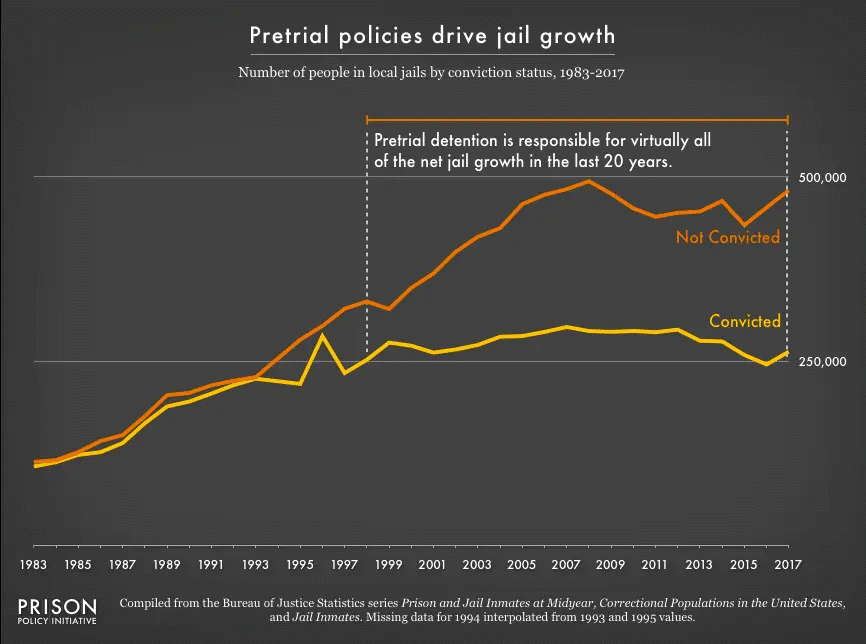

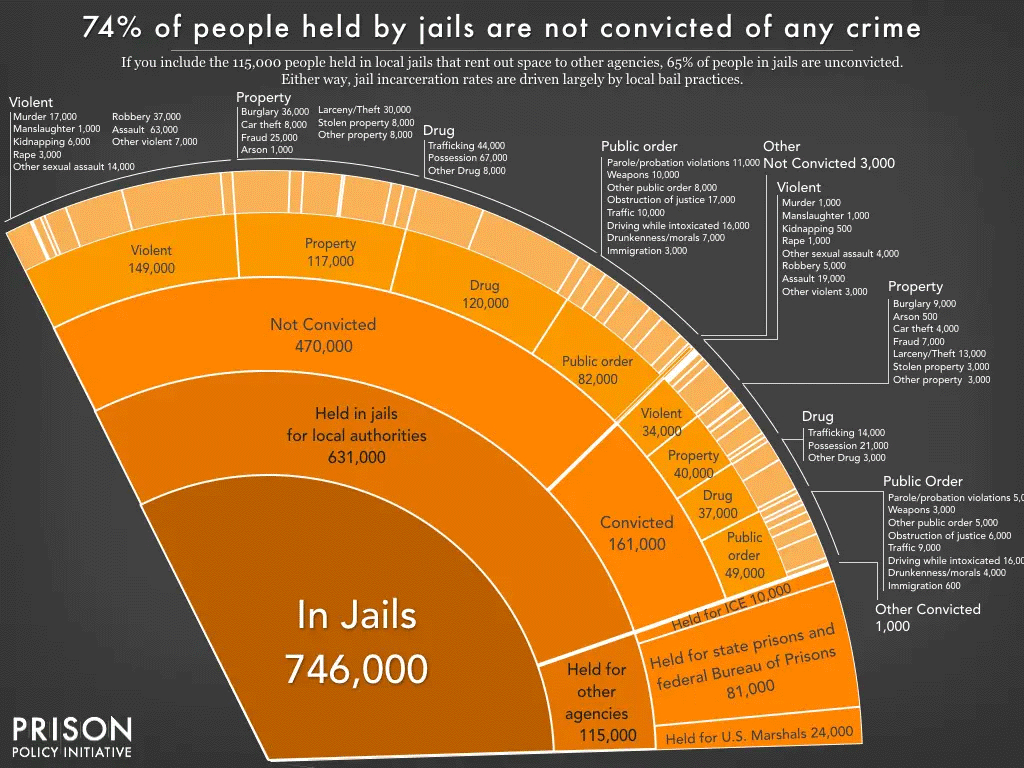

This big-picture view allows us to focus on the most important drivers of mass incarceration and identify important, but often ignored, systems of confinement. The detailed views bring these overlooked systems to light, from immigration detention to civil commitment and youth confinement. In particular, local jails often receive short shrift in larger discussions about criminal justice, but they play a critical role as "incarceration's front door" and have a far greater impact than the daily population suggests.

While this pie chart provides a comprehensive snapshot of our correctional system, the graphic does not capture the enormous churn in and out of our correctional facilities, nor the far larger universe of people whose lives are affected by the criminal justice system. Every year, over 600,000 people enter prison gates, but people go to jail 10.6 million times each year. 2 Jail churn is particularly high because most people in jails have not been convicted. 3 Some have just been arrested and will make bail within hours or days, while many others are too poor to make bail and remain behind bars until their trial. Only a small number (about 160,000 on any given day) have been convicted, and are generally serving misdemeanors sentences under a year. At least 1 in 4 people who go to jail will be arrested again within the same year — often those dealing with poverty, mental illness, and substance use disorders, whose problems only worsen with incarceration.

There are more graphics, here, in the Original Article , including these two:

With a sense of the big picture, the next question is: why are so many people locked up? How many are incarcerated for drug offenses? Are the profit motives of private companies driving incarceration? Or is it really about public safety and keeping dangerous people off the streets? There are a plethora of modern myths about incarceration. Most have a kernel of truth, but these myths distract us from focusing on the most important drivers of incarceration.

Five myths about mass incarceration

The overcriminalization of drug use, the use of private prisons, and low-paid or unpaid prison labor are among the most contentious issues in criminal justice today because they inspire moral outrage. But they do not answer the question of why most people are incarcerated, or how we can dramatically — and safely — reduce our use of confinement. Likewise, emotional responses to sexual and violent offenses often derail important conversations about the social, economic, and moral costs of incarceration and lifelong punishment. Finally, simplistic solutions to reducing incarceration, such as moving people from jails and prisons to community supervision, ignore the fact that "alternatives" to incarceration often lead to incarceration anyway. Focusing on the policy changes that can end mass incarceration, and not just put a dent in it, requires the public to put these issues into perspective.

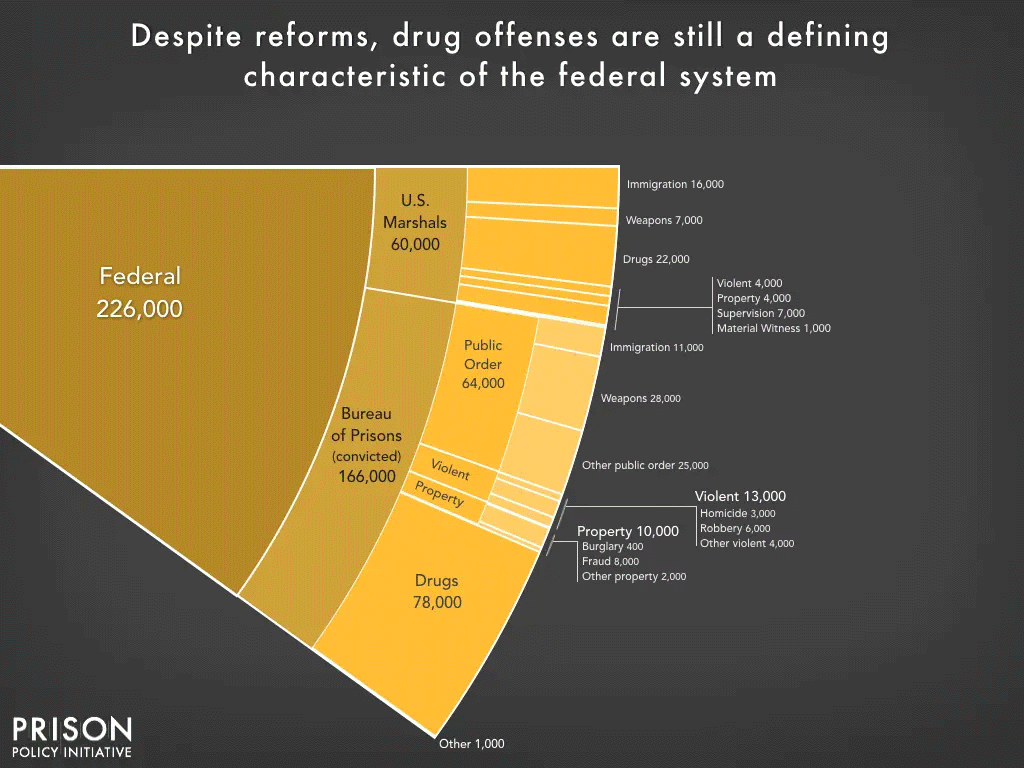

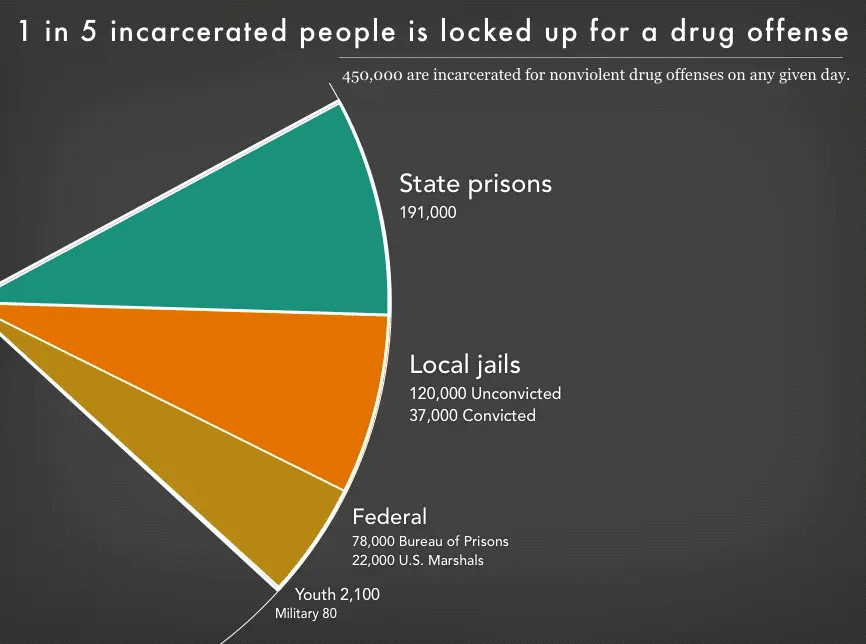

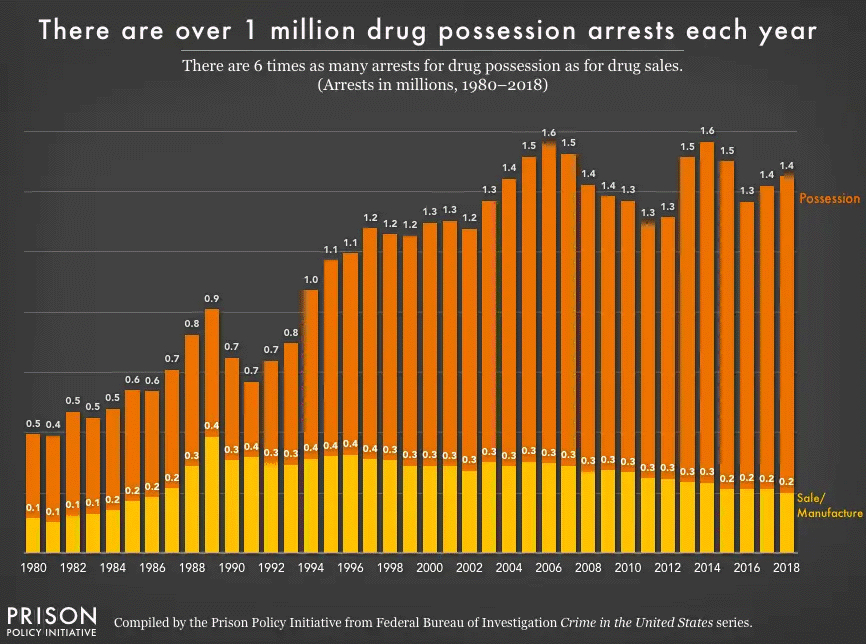

The first myth: Releasing "nonviolent drug offenders" would end mass incarceration

It's true that police, prosecutors, and judges continue to punish people harshly for nothing more than drug possession. Drug offenses still account for the incarceration of almost half a million people, 4 and nonviolent drug convictions remain a defining feature of the federal prison system. Police still make over 1 million drug possession arrests each year, 5 many of which lead to prison sentences. Drug arrests continue to give residents of over-policed communities criminal records, hurting their employment prospects and increasing the likelihood of longer sentences for any future offenses.

Nevertheless, 4 out of 5 people in prison or jail are locked up for something other than a drug offense — either a more serious offense or an even less serious one. To end mass incarceration, we will have to change how our society and our justice system responds to crimes more serious than drug possession. We must also stop incarcerating people for behaviors that are even more benign.

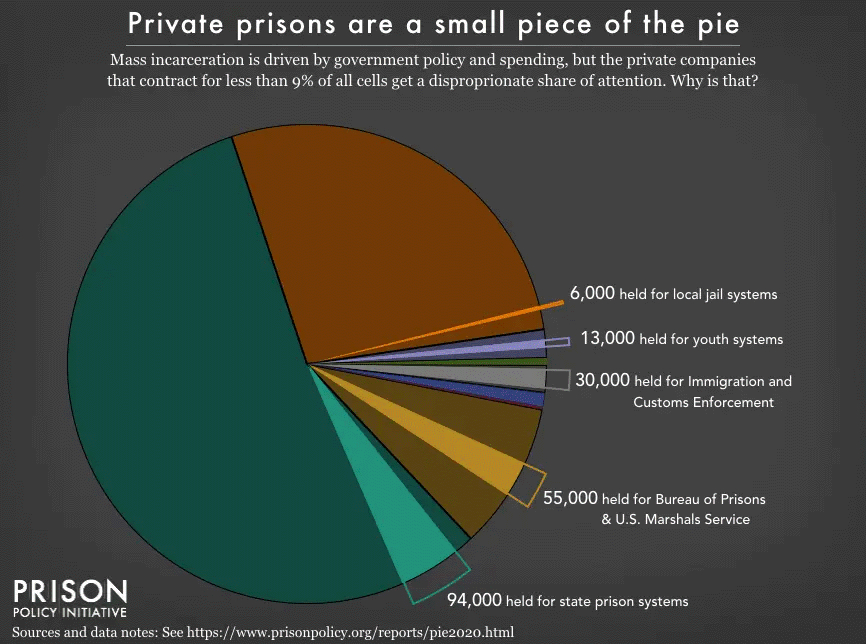

The second myth: Private prisons are the corrupt heart of mass incarceration

In fact, less than 9% of all incarcerated people are held in private prisons; the vast majority are in publicly-owned prisons and jails. 6 Some states have more people in private prisons than others, of course, and the industry has lobbied to maintain high levels of incarceration, but private prisons are essentially a parasite on the massive publicly-owned system — not the root of it.

Nevertheless, a range of private industries and even some public agencies continue to profit from mass incarceration. Many city and county jails rent space to other agencies, including state prison systems, 7 the U.S. Marshals Service, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Private companies are frequently granted contracts to operate prison food and health services (often so bad they result in major lawsuits), and prison and jail telecom and commissary functions have spawned multi-billion dollar private industries. By privatizing services like phone calls, medical care and commissary, prisons and jails are unloading the costs of incarceration onto incarcerated people and their families, trimming their budgets at an unconscionable social cost.

Private prisons and jails hold less than 9 percent of all incarcerated people, making them a relatively small part of a mostly publicly-run correctional system.

The third myth: Prisons are "factories behind fences" that exist to provide companies with a huge slave labor force

Simply put, private companies using prison labor are not what stands in the way of ending mass incarceration, nor are they the source of most prison jobs. Only about 5,000 people in prison — less than 1% — are employed by private companies through the federal PIECP program, which requires them to pay at least minimum wage before deductions. (A larger portion work for state-owned "correctional industries," which pay much less, but this still only represents about 6% of people incarcerated in state prisons.) 8

But prisons do rely on the labor of incarcerated people for food service, laundry and other operations, and they pay incarcerated workers unconscionably low wages: our 2017 study found that on average, incarcerated people earn between 86 cents and $3.45 per day for the most common prison jobs. In at least five states, those jobs pay nothing at all. Moreover, work in prison is compulsory, with little regulation or oversight, and incarcerated workers have few rights and protections. Forcing people to work for low or no pay and no benefits allows prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people — hiding the true cost of running prisons from most Americans.

The fourth myth: People in prison for violent or sexual crimes are too dangerous to be released

Particularly harmful is the myth that people who commit violent or sexual crimes are incapable of rehabilitation and thus warrant many decades or even a lifetime of punishment. As lawmakers and the public increasingly agree that past policies have led to unnecessary incarceration, it's time to consider policy changes that go beyond the low-hanging fruit of "non-non-nons" — people convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses. If we are serious about ending mass incarceration, we will have to change our responses to more serious and violent crime.

Recidivism: A slippery statistic

How much do different measures of recidivism reflect actual failure or success upon reentry?

As long as we are considering recidivism rates as a measure of public safety risk, we should also consider how recidivism is defined and measured. While this may sound esoteric, this is an issue that affects an important policy question: at what point — and with what measure — do we consider someone's re-entry a success or failure?

The term "recidivism" suggests a relapse in behavior, a return to criminal offending. But what is a valid sign of criminal offending: self-reported behavior, arrest, conviction, or incarceration? Defining recidivism as rearrest casts the widest net and results in the highest rates, but arrest does not suggest conviction, nor actual guilt. More useful measures than rearrest include conviction for a new crime, re-incarceration, or a new sentence of imprisonment; the latter may be most relevant, since it measures offenses serious enough to warrant a prison sentence. Importantly, people convicted of violent offenses have the lowest recidivism rates by each of these measures. However, the recidivism rate for violent offenses is a whopping 48 percentage points higher when rearrest, rather than imprisonment, is used to define recidivism.

The cutoff point at which recidivism is measured also matters: If someone is arrested for the first time 5, 10, or 20 years after they leave prison, that's very different from someone arrested within months of release. The most recent government study of recidivism reported that 83% of state prisoners were arrested at some point in the 9 years following their release, but the vast majority of those were arrested within the first 3 years, and more than half within the first year. The longer the time period, the higher the reported recidivism rate — but the lower the actual threat to public safety.

A related question is whether it matters what the post-release offense is. For example, 71% of people imprisoned for a violent offense are rearrested within 5 years of release, but only 33% are rearrested for another violent offense; they are much more likely to be rearrested for a public order offense. If someone convicted of robbery is arrested years later for a liquor law violation, it makes no sense to view this very different, much less serious, offense the same way we would another arrest for robbery.

A final note about recidivism: While policymakers frequently cite reducing recidivism as a priority, few states collect the data that would allow them to monitor and improve their own performance in real time. For example, the Council of State Governments asked correctional systems what kind of recidivism data they collect and publish for people leaving prison and people starting probation. What they found is that states typically track just one measure of post-release recidivism, and few states track recidivism while on probation at all:

If state-level advocates and political leaders want to know if their state is even trying to reduce recidivism, we suggest one easy litmus test: Do they collect and publish basic data about the number and causes of people's interactions with the justice system while on probation, or after release from prison?

Recidivism data do not support the belief that people who commit violent crimes ought to be locked away for decades for the sake of public safety. People convicted of violent and sexual offenses are actually among the least likely to be rearrested, and those convicted of rape or sexual assault have rearrest rates 20% lower than all other offense categories combined. More broadly, people convicted of any violent offense are less likely to be rearrested in the years after release than those convicted of property, drug, or public order offenses. One reason: age is one of the main predictors of violence. The risk for violence peaks in adolescence or early adulthood and then declines with age, yet we incarcerate people long after their risk has declined.

Despite this evidence, people convicted of violent offenses often face decades of incarceration, and those convicted of sexual offenses can be committed to indefinite confinement or stigmatized by sex offender registries long after completing their sentences. And while some of the justice system's response has more to do with retribution than public safety, more incarceration is not what most victims of crime want. National survey data show that most victims want violence prevention, social investment, and alternatives to incarceration that address the root causes of crime, not more investment in carceral systems that cause more harm.

The fifth myth: Expanding community supervision is the best way to reduce incarceration

Community supervision, which includes probation, parole, and pretrial supervision, is often seen as a "lenient" punishment, or as an ideal "alternative" to incarceration. But while remaining in the community is certainly preferable to being locked up, the conditions imposed on those under supervision are often so restrictive that they set people up to fail. The long supervision terms, numerous and burdensome requirements, and constant surveillance (especially with electronic monitoring) result in frequent "failures," often for minor infractions like breaking curfew or failing to pay unaffordable supervision fees.

In 2016, at least 168,000 people were incarcerated for such "technical violations" of probation or parole — that is, not for any new crime. 9 Probation, in particular, leads to unnecessary incarceration; until it is reformed to support and reward success rather than detect mistakes, it is not a reliable "alternative."

The high costs of low-level offenses

Most justice-involved people in the U.S. are not accused of serious crimes; more often, they are charged with misdemeanors or non-criminal violations. Yet even low-level offenses, like technical violations of probation and parole, can lead to incarceration and other serious consequences. Rather than investing in community-driven safety initiatives, cities and counties are still pouring vast amounts of public resources into the processing and punishment of these minor offenses.

Probation & parole violations and "holds" lead to unnecessary incarceration

Often overlooked in discussions about mass incarceration are the various "holds" that keep people behind bars for administrative reasons. A common example is when people on probation or parole are jailed for violating their supervision, either for a new crime or a "technical violation." If a parole or probation officer suspects that someone has violated supervision conditions, they can file a "detainer" (or "hold"), rendering that person ineligible for release on bail. For people struggling to rebuild their lives after conviction or incarceration, returning to jail for a minor infraction can be profoundly destabilizing. The national data do not exist to say exactly how many people are in jail because of probation or parole violations or detainers, but initial evidence shows that these account for over one-third of some jail populations. This problem is not limited to local jails, either; in 2019, the Council of State Governments found that 1 in 4 people in state prisons are incarcerated as a result of supervision violations.

Misdemeanors: Minor offenses with major consequences

The "massive misdemeanor system" in the U.S. is another important but overlooked contributor to overcriminalization and mass incarceration. For behaviors as benign as jaywalking or sitting on a sidewalk, an estimated 13 million misdemeanor charges sweep droves of Americans into the criminal justice system each year (and that's excluding civil violations and speeding). These low-level offenses account for over 25% of the daily jail population nationally, and much more in somestates and counties.

Misdemeanor charges may sound like small potatoes, but they carry serious financial, personal, and social costs, especially for defendants but also for broader society, which finances the processing of these court cases and all of the unnecessary incarceration that comes with them. And then there are the moral costs: People charged with misdemeanors are often not appointed counsel and are pressured to plead guilty and accept a probation sentence to avoid jail time. This means that innocent people routinely plead guilty, and are then burdened with the many collateral consequences that come with a criminal record, as well as the heightened risk of future incarceration for probation violations. A misdemeanor system that pressures innocent defendants to plead guilty seriously undermines American principles of justice.

"Low-level fugitives" live in fear of incarceration for missed court dates and unpaid fines

Defendants can end up in jail even if their offense is not punishable with jail time. Why? Because if a defendant fails to appear in court or to pay fines and fees, the judge can issue a "bench warrant" for their arrest, directing law enforcement to jail them in order to bring them to court. While there is currently no national estimate of the number of active bench warrants, their use is widespread and in some places, incredibly common. In Monroe County, N.Y., for example, over 3,000 people have an active bench warrant at any time, more than 3 times the number of people in the county jails.

But bench warrants are often unnecessary. Most people who miss court are not trying to avoid the law; more often, they forget, are confused by the court process, or have a schedule conflict. Once a bench warrant is issued, however, defendants frequently end up living as "low-level fugitives," quitting their jobs, becoming transient, and/or avoiding public life (even hospitals) to avoid having to go to jail.

Offense categories might not mean what you think

To understand the main drivers of incarceration, the public needs to see how many people are incarcerated for different offense types. But the reported offense data oversimplifies how people interact with the criminal justice system in two important ways: it reports only one offense category per person, and it reflects the outcome of the legal process, obscuring important details of actual events.

First, when a person is in prison for multiple offenses, only the most serious offense is reported. 10 So, for example, there are people in prison for violent offenses who were also convicted of drug offenses, but they are included only in the "violent" category in the data. This makes it hard to grasp the complexity of criminal events, such as the role drugs may have played in violent or property offenses. We must also consider that almost all convictions are the result of plea bargains, where defendants plead guilty to a lesser offense, possibly in a different category, or one that they did not actually commit.

Secondly, many of these categories group together people convicted of a wide range of offenses. For violent offenses especially, these labels can distort perceptions of individual "violent offenders" and exaggerate the scale of dangerous violent crime. For example, "murder" is an extremely serious offense, but that category groups together the small number of serial killers with people who committed acts that are unlikely, for reasons of circumstance or advanced age, to ever happen again. It also includes offenses that the average person may not consider to be murder at all. In particular, the felony murder rule says that if someone dies during the commission of a felony, everyone involved can be as guilty of murder as the person who pulled the trigger. Acting as lookout during a break-in where someone was accidentally killed is indeed a serious offense, but many may be surprised that this can be considered murder in the U.S. 11

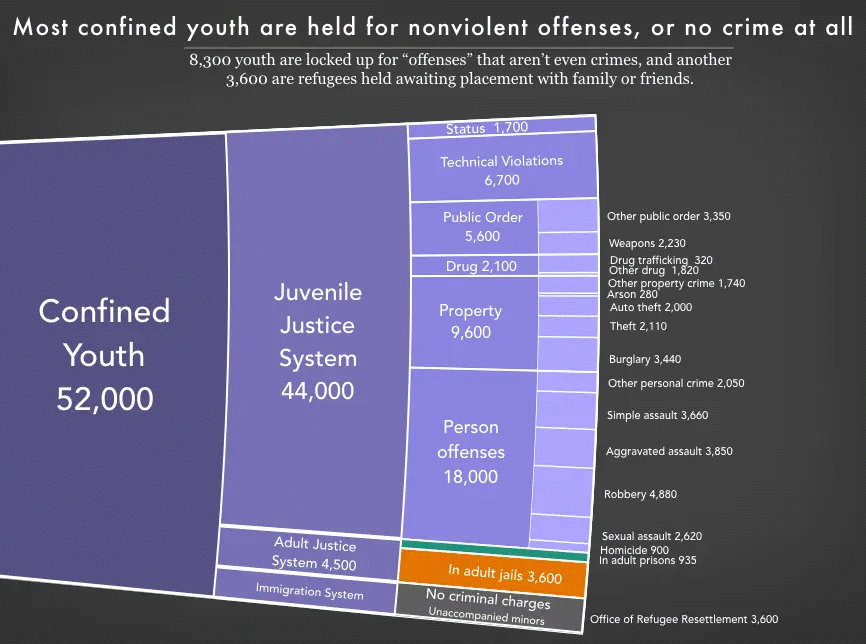

Lessons from the smaller "slices": Youth, immigration, and involuntary commitment

Looking more closely at incarceration by offense type also exposes some disturbing facts about the 52,000 youth in confinement in the United States: too many are there for a "most serious offense" that is not even a crime . For example, there are over 6,600 youth behind bars for technical violations of their probation, rather than for a new offense. An additional 1,700 youth are locked up for "status" offenses, which are "behaviors that are not law violations for adults, such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility." 12 Nearly 1 in 10 youth held for a criminal or delinquent offense is locked in an adult jail or prison, and most of the others are held in juvenile facilities that look and operate a lot like prisons and jails.

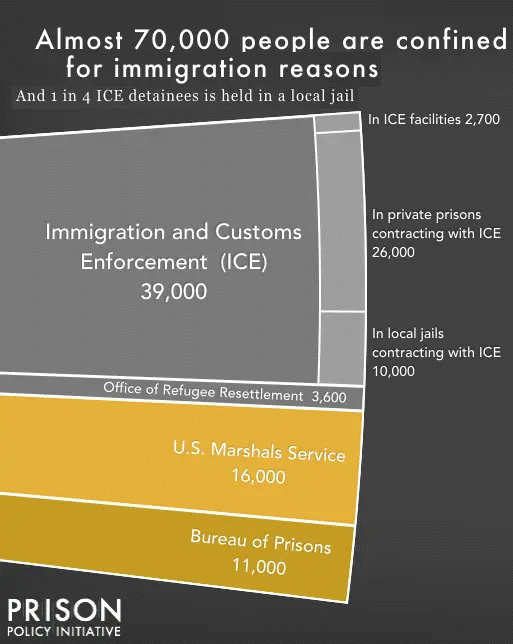

Turning to the people who are locked up criminally and civilly for immigration-related reasons , we find that 11,100 people are in federal prisons for criminal convictions of immigration offenses, and 13,600 more are held pretrial by the U.S. Marshals. The vast majority of people incarcerated for criminal immigration offenses are accused of illegal entry or illegal re-entry — in other words, for no more serious offense than crossing the border without permission. 13

Another 39,000 people are civilly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) not for any crime, but simply for their undocumented immigrant status. ICE detainees are physically confined in federally-run or privately-run immigration detention facilities, or in local jails under contract with ICE. An additional 3,600 unaccompanied children are held in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), awaiting placement with parents, family members, or friends. While these children are not held for any criminal or delinquent offense, most are held in shelters or even juvenile placement facilities under detention-like conditions. 14

Adding to the universe of people who are confined because of justice system involvement, 22,000 people are involuntarily detained or committed to state psychiatric hospitals and civil commitment centers. Many of these people are not even convicted, and some are held indefinitely. 9,000 are being evaluated pre-trial or treated for incompetency to stand trial; 6,000 have been found not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but mentally ill; another 6,000 are people convicted of sexual crimes who are involuntarily committed or detained after their prison sentences are complete. While these facilities aren't typically run by departments of correction, they are in reality much like prisons.

Beyond the "Whole Pie": Community supervision, poverty, and race and gender disparities

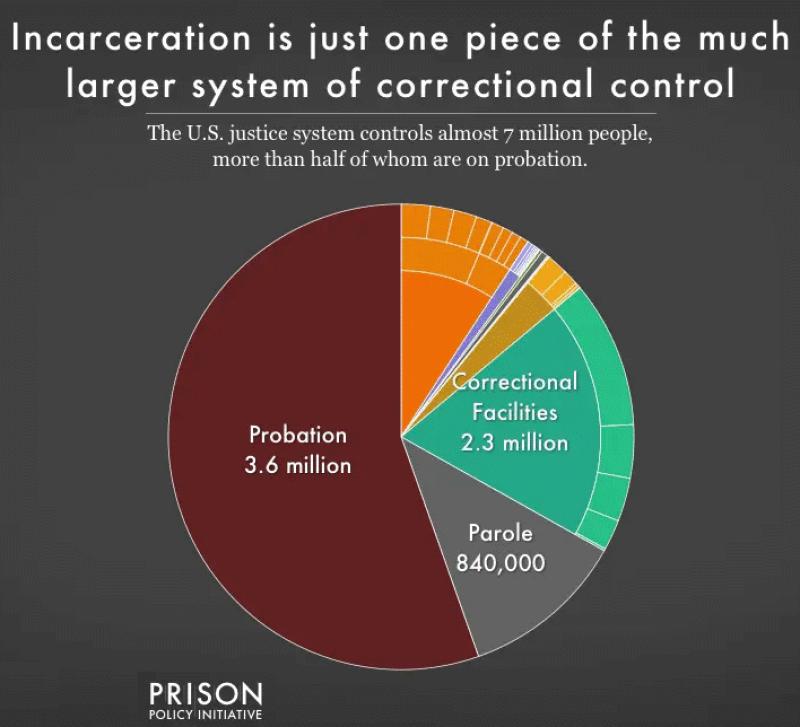

Once we have wrapped our minds around the "whole pie" of mass incarceration, we should zoom out and note that people who are incarcerated are only a fraction of those impacted by the criminal justice system. There are another 840,000 people on parole and a staggering 3.6 million people on probation. Many millions more have completed their sentences but are still living with a criminal record, a stigmatizing label that comes with collateral consequences such as barriers to employment and housing.

Beyond identifying how many people are impacted by the criminal justice system, we should also focus on who is most impacted and who is left behind by policy change. Poverty, for example, plays a central role in mass incarceration. People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor compared to the overall U.S. population. 15 The criminal justice system punishes poverty, beginning with the high price of money bail: The median felony bail bond amount ($10,000) is the equivalent of 8 months' income for the typical detained defendant. As a result, people with low incomes are more likely to face the harms of pretrial detention. Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration; it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth, creates debt, and decimates job opportunities. 16

It's no surprise that people of color — who face much greater rates of poverty — are dramatically overrepresented in the nation's prisons and jails. These racial disparities are particularly stark for Black Americans, who make up 40% of the incarcerated population despite representing only 13% of U.S residents. The same is true for women, whose incarceration rates have for decades risen faster than men's, and who are often behind bars because of financial obstacles such as an inability to pay bail. As policymakers continue to push for reforms that reduce incarceration, they should avoid changes that will widen disparities, as has happened with juvenile confinement and with women in state prisons.

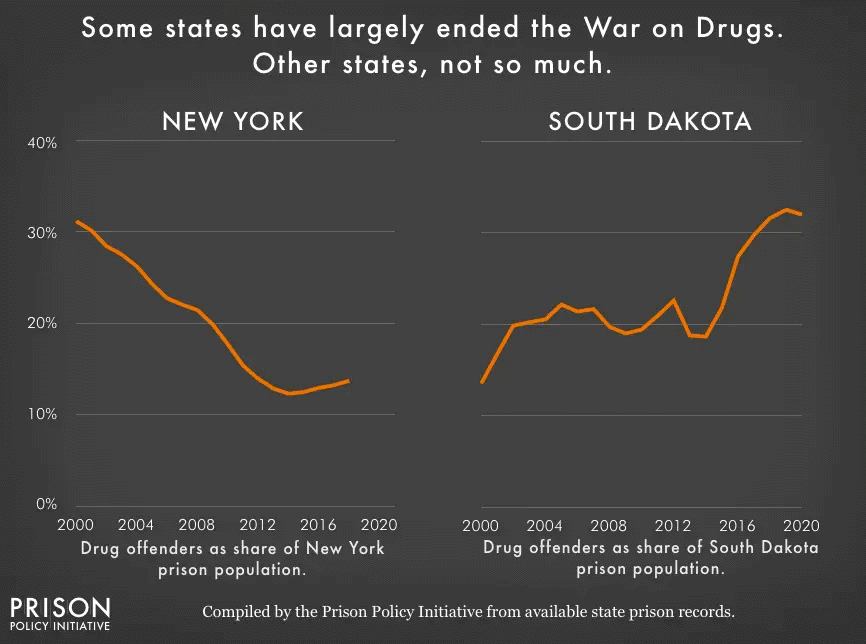

Equipped with the full picture of how many people are locked up in the United States, where, and why, our nation has a better foundation for the long overdue conversation about criminal justice reform. For example, the data makes it clear that ending the war on drugs will not alone end mass incarceration, though the federal government and some states have taken an important step by reducing the number of people incarcerated for drug offenses. Looking at the "whole pie" also opens up other conversations about where we should focus our energies:

- Are state officials and prosecutors willing to rethink not just long sentences for drug offenses, but the reflexive, simplistic policymaking that has served to increase incarceration for violent offenses as well?

- Do policymakers and the public have the stamina to confront the second largest slice of the pie: the thousands of locally administered jails? Will state, county, and city governments be brave enough to end money bail without imposing unnecessary conditions in order to bring down pretrial detention rates? Will local leaders be brave enough to redirect public spending to smarter investments like community-based drug treatment and job training?

- What is the role of the federal government in ending mass incarceration? The federal prison system is just a small slice of the total pie, but the federal government can certainly use its financial and ideological power to incentivize and illuminate better paths forward. At the same time, how can elected sheriffs, district attorneys, and judges — who all control larger shares of the correctional pie — slow the flow of people into the criminal justice system?

- Given that the companies with the greatest impact on incarcerated people are not private prison operators, but service providers that contract with public facilities, will states respond to public pressure to end contracts that squeeze money from people behind bars?

- Can we implement reforms that both reduce the number of people incarcerated in the U.S. and the well-known racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system?

Now that we can see the big picture of how many people are locked up in the United States in the various types of facilities, we can see that something needs to change . Looking at the big picture requires us to ask if it really makes sense to lock up 2.3 million people on any given day, giving this nation the dubious distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world. Both policymakers and the public have the responsibility to carefully consider each individual slice in turn to ask whether legitimate social goals are served by putting each group behind bars, and whether any benefit really outweighs the social and fiscal costs.

Even narrow policy changes, like reforms to money bail, can meaningfully reduce our society's use of incarceration. At the same time, we should be wary of proposed reforms that seem promising but will have only minimal effect, because they simply transfer people from one slice of the correctional "pie" to another. Keeping the big picture in mind is critical if we hope to develop strategies that actually shrink the "whole pie."

The Original Article has quite a few more graphics,

and an entire section on data analysis and treatment.

Tags

Who is online

30 visitors

Very enlightening. Lots of my preconceptions fared very poorly...

For example:

Eisenhower should have warned us of the dangers posed to freedom by the Industrial Prison Complex!