The Secret Mosquito Stash

When Airbus Industries prepared to bulldoze a small World War II-era building at its Broughton, England facility last August, the crew found something astonishing: thousands of forgotten 80-year-old technical drawings for the de Havilland Mosquito, at one time the fastest aircraft in the world. Demolition was halted while Airbus contacted The People’s Mosquito, a U.K. charity hoping to restore and fly a version of the Royal Air Force’s versatile twin-engine bomber, and asked if they’d be interested in the documents.

John Lilley, chairman of The People’s Mosquito, immediately drove to the site. “When he got there,” says Ross Sharp, the charity’s director of engineering and airframe compliance, “he found himself staring at a filing cabinet full of more than 22,000 aperture cards.” (An aperture card is a microfilm image mounted on stiff card stock.) “It was an emergency situation,” Sharp continues, “so they put the cards—all 148 pounds of them—into refuse bags and loaded them into his car.”

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/de/d9/ded9779a-a2b3-444c-89f4-4aa506638e2d/24i_dj2018_si-72-8523_live-wr.jpg) A Mosquito in flight; of the more than 7,000 built, only three known airworthy examples survive

A Mosquito in flight; of the more than 7,000 built, only three known airworthy examples survive

NASM (72-8523)

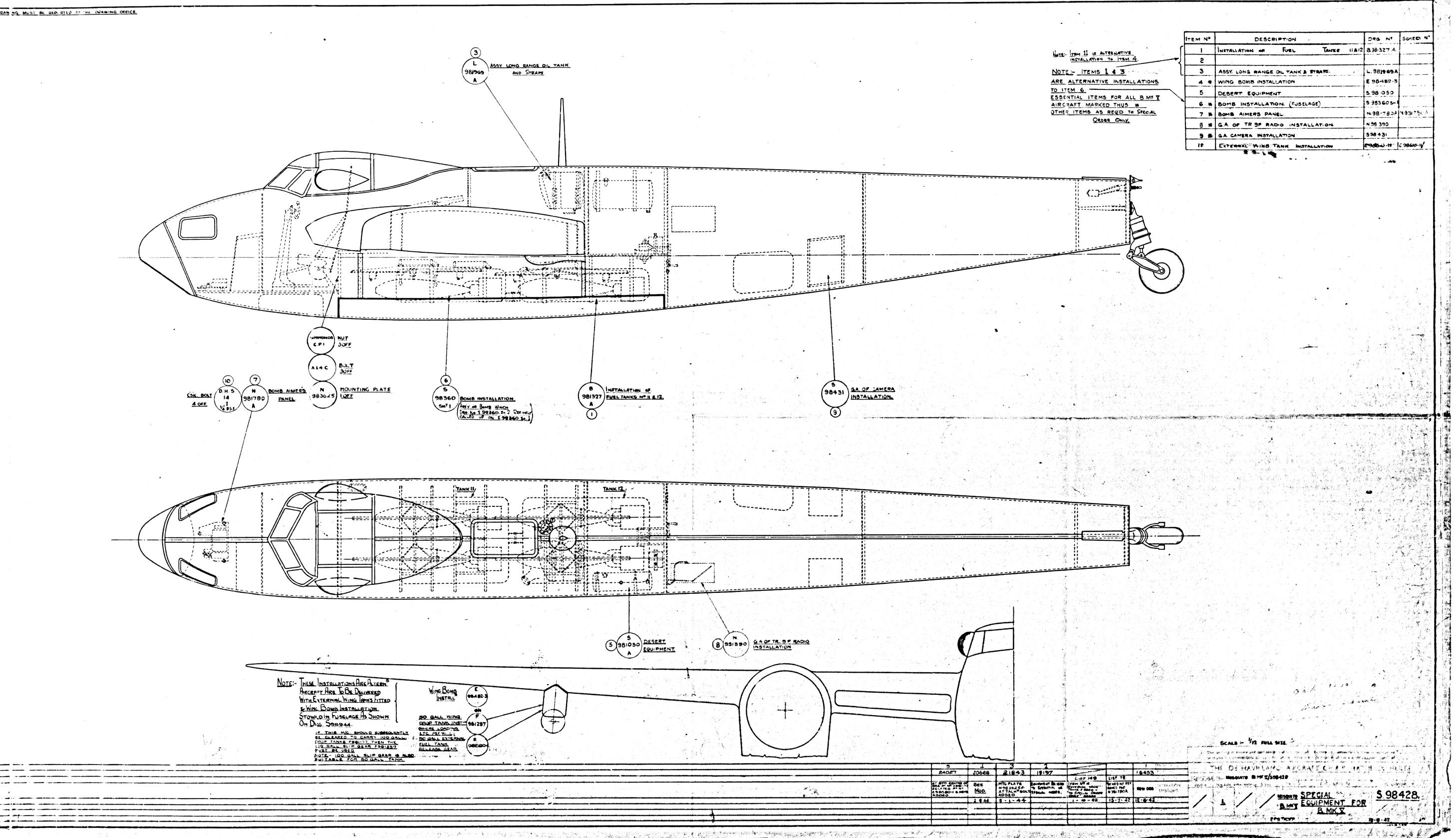

The cards, some in need of restoration themselves, were immediately scanned, at a cost of about $6,000. Sharp’s job is to assess their relevance; he is almost halfway through the collection. “Some of these drawings have an ethereal beauty,” he says, “although they contain much more than drawings, in that some include scribbled notes and rough sketches. Some of the cards contain annotations, things like ‘first two prototypes only.’ You are actually looking at a complete history of an aircraft, its evolution and its variants, including unbuilt versions.”

“The Mosquito FB.XVIII—sometimes known as the Tsetse—was highly unusual,” says Ross Sharp

“The Mosquito FB.XVIII—sometimes known as the Tsetse—was highly unusual,” says Ross Sharp

“An FB.VI was modified to carry a 57mm field gun; obviously such a huge weapon was difficult to fit

into the Mosquito, and the nose had to be strengthened.

(The first time it was fired — on the ground — the nose cap was buckled by the blast.)”

A total of just 18 of these attack aircraft were produced.

The People’s Mosquito

“The Mosquito was always intended to be used in defence of Britain’s far-flung Empire,” says Sharp.

“The Mosquito was always intended to be used in defence of Britain’s far-flung Empire,” says Sharp.

“Consequently, a drawing assigned to ‘Mosquito Mk I, Tropics’ shows a full-set of desert equipment.

As well as a large water tank and individual water bottles and emergency rations,

the rear fuselage contains communications aids (hand mirror, signal strips),

aircraft picking gear and a tool kit. Also provided was a hand starting handle for the Merlin engines!”

The People’s Mosquito

It makes sense that the documents were found at the Airbus facility; it was a de Havilland factory during the war, but much more recently serviced British Aerospace’s DH.98 Mosquito — the last airworthy Mosquito in all of Europe — until its crash at the Barton airshow in 1996. The documents are a mix of British Aerospace, Hawker Siddeley (the predecessor to British Aerospace) and de Havilland drawings, making classification a challenge. “I opened up one the other day,” says Sharp, “and I thought Wait a minute! That’s not a Mosquito — unless we suddenly started building a biplane version. It was actually specifications on how to completely re-cover, with Irish linen, a de Havilland Tiger Moth. The drawing just snuck in there.”

“Initially specified to carry just 4 x 250-lb bombs,” says Sharp, “the bomber version of the Mosquito

“Initially specified to carry just 4 x 250-lb bombs,” says Sharp, “the bomber version of the Mosquito

had its warload doubled by some thoughtful engineering on the part of the de Havilland team.

The company developed a specially-shortened tail fin for the standard RAF 500lb MC (Medium Case) bomb,

thereby allowing four of these to be fitted into the Mosquito’s bomb bay.

Observe the slight nose-down angle of the rear pair of bombs when secured on their bomb beam.

Other ordnance, including 250-lb SAP (Semi-Armour Piercing), 500-lb GP (General Purpose)

or SBC (Small Bomb Containers) could be carried.

Later in the war, bomber versions of the Mosquito were built which could carry the monstrous

4,000 HC (High Capacity) blast bomb.

This infamous ‘cookie’ was a much feared weapon, even by RAF crews, as it could not be dropped ‘safe.’ ”

The People’s Mosquito

The drawings will help the organization in its restoration of a Mosquito NF.36 that crashed near RAF Coltishall airfield in February 1949. Instead of having to reverse-engineer parts of the bomber—a time-consuming and costly process—they can simply get the specs for the parts from the drawings.

“Things like the main hydraulic reservoir, that stands out,” says Sharp. “And we now have drawings for the internal baffles for the main fuel tanks. And there are minor things, like how to construct the navigator’s folding seat, its precise layout and the actual cotton and wadding that you use. It’s rather elegant.” The cost of the restoration is estimated at $9 million; if the entire funding were in place, says Sharp, the aircraft could be completed in about three and a half years.

“In the Mosquito,” says Sharp, “the navigator (who also doubled as the bomb aimer or radar operator)

“In the Mosquito,” says Sharp, “the navigator (who also doubled as the bomb aimer or radar operator)

was seated slightly behind and to the right of the pilot on a folding seat.

Before material shortages really took hold, this was constructed of pieces of sorbo rubber on a plywood frame

covered with green upholstery leather. You can see the result of wartime austerity on the right side of the drawing.

Quilted pads of cotton waste and open-weave cotton fabric are dividing layers of kapok,

which has replaced the sorbo rubber.

The leather is also gone, with ‘green, fire-proofed upholstery cloth’ used as a substitute.

The back of the seat is now covered in ‘strong canvas.’ ”

The People’s Mosquito

Restoration has already begun; Aerowood Ltd., an aviation wood specialist in New Zealand, has started production on the aircraft’s wing ribs, using Canadian spruce cut from the same area—Queen Charlotte Islands—that generated lumber for wartime Mosquitoes produced by de Havilland Canada. During the war, 900 men—“former wrestlers, boxers, and local tough guys,” reported the Hartford Courant in 1943—worked 10-hour days cutting spruce trees for airplane production. “There are six main woods used in the Mosquito,” says Sharp, “all engineered, brilliantly, for what they do. Only one in 10 spruce trees were actually capable of meeting the exacting specifications for the aircraft.”

The airplane, known as the “Wooden Wonder” was originally built to be an unarmed fast bomber, but proved so versatile it was used as a night fighter, for photo-reconnaissance, as a light bomber, and as a maritime strike aircraft. Of the more than 7,000 Mosquitoes built, only a handful remain, and only three known airworthy examples survive, two in the United States, and one in Canada. The discovery of these priceless drawings has galvanized the members of The People’s Mosquito, who hope to see the aircraft once again flying over Britain. “We must fly and we must educate and we must remember,” says Sharp, “and honor all of those who have served in the Mosquito, including those that built her. And that’s just what we’re doing.”

“The Mosquito was constantly being developed throughout its service life,” says Sharp.

“The Mosquito was constantly being developed throughout its service life,” says Sharp.

“The B. Mk V was a direct modification of the early bomber version, the B.Mk IV. but with a new, standard wing.

This was capable, as seen here, of carrying either 50-gallon drop tanks or, initially, 250-lb bombs.

Only one B. Mk V was built, but a small series of B. Mk VII bombers were built by de Havilland Canada.

This aircraft was intended for long missions, as it could carry overload fuel tanks in the bomb bay,

and was equipped with a long range oil tank, to handle the increased oil consumption of the twin Merlins.”

The People’s Mosquito

=============================

There may be links in the Original Article that have not been reproduced here.

I love this stuff!

Right-click on the images to open a bigger copy.

She was a remarkable and versatile aircraft

Cool stuff .... thx!

I remember when hand drafting was an art form. Now it’s all CAD, and no new CAD draftsman has any concept of the care and dedication that used to go into the hand drafting process. I use CAD exclusively every day at work, and my goal is to produce drawings that reflect the professionalism of old school hand drafting. Unfortunately, most of my colleagues are either too young to have experienced the art of competent hand drafting, or have given up the art and succumbed to the ease of making really shitty looking drawings fast and carelessly with CAD.

Do the youngsters understand the phrase, "Back to the drawing board"?

I was working for a semi-trailer manufacturer when CAD arrived. In less than five years, the Engineering Office went from about forty drawing boards to... two, for legacy drawings.

There were a few errors directly attributable to CAD, including the classic: insufficient tolerances in mechanical assemblies, because "it looked OK on the screen!"

It's amazing how far technology has taken us. I'm a civil engineer, so I work with topographic surveys every day. Back in the day I spent many hours out in the field doing the actual topographic surveying as well, using instruments that were advanced for the time but are now nearly obsolete. In a traditional topo survey, the location of an object is represented by a point on a drawing, typically with some notation for the draftsman or engineer to place a symbol.

For example, a tree would be located with a three dimensional coordinate, and the note would indicate that it is a tree of a certain diameter. Some of he oldest tools for doing this would involve a level, steel measuring tape, and a level rod, requiring two people. Later, a laser type of device was developed, called a total station, eliminating the need for the steel measuring tape and level rod, but still requiring two people. This was a major advancement in the survey industry. Then came the robotic total station, that only required one person. Then came gps, which amazingly uses satellites that track a single person on the ground to record points. This sometimes has its limitations, because tree canopy can obscure the satellite.

Recently, I was working with a topo survey and the location of a tree was there, but it was missing the notation of its diameter. Using google maps street view, I was able to ascertain that it was a larger diameter tree, thus it was important to verify its size to determine if we needed to modify our design to work around it. Rather than drive out to the site, I called the surveyor to see if he might have some field notes indicating its size. He said no problem, the tree had been picked up with the latest survey technique, LiDAR - and he sent me this:

I can't even really explain how LiDAR works, because it is currently beyond my comprehension. But basically, its a device that is driven around, and it sprays its environment with millions of laser pulses, which reflect back from everything within range, and record locational data with exceptional accuracy. Though the data dump is enormous, you can literally pan though the 3d virtual file, observe the surroundings, and measure things if need be. It blows my mind. Instead of having a topo survey with a tree represented by a single point, modern topo survey techniques will allow for a tree to be composed of thousands of three dimensional points - outlining the tree and even the leaves!

I expect that before I retire, the typical civil engineering office will have a drone that is equipped with LiDAR. If information is needed from the field, it will be routine to just feed the drone some coordinates and have the information picked up without even leaving your seat.

... you'll make your request to an AI which will organize and execute the mission with no human intervention..

Light Detection And Ranging.

Same principle as Sonar except using low-powered pinpoint Lasers.

The laser sends out a pulse of light and sensors pick up the reflection.

The Washington Department of Natural Resources uses it for all kinds of stuff.

I expect that the military has been using it for at least a decade.....

And it is probably going to make the self driving car a lot safer as soon as they get the size and costs down.....

I recently finished The Lost City of the Monkey God, by Douglas Preston. It's the true story of a group of archeologists who uncovered an enormous city of ancient ruins in Honduras using LiDAR. From the air the area was totally camouflaged with impenetrable jungle so thick, that even if you were standing on collapsed piece of ancient architecture you wouldn't know it. The LiDAR instrument, which was a heavily guarded secret military device, was loaded on a plane and the area was scanned from above. For every 1,000 or so laser pulses that bounced off of vegetation, maybe one or two found their way to the ground through tiny unobstructed corridors, like the way you would see small bits of sunshine on the jungle floor that managed to get through the tree canopy. By filtering out all the higher data, enough of the jungle floor was revealed to show clear evidence of ruins that would have taken decades of searching for by traditional archeological means. Very good read.

Cool

LOL, I was just going to post on finding the City of the Monkey God...

IMO the drawing are priceless. What a find.