A New Species of Giant Octopus Has Been Hiding in Plain Sight

You wouldn’t think a giant octopus could hide in plain sight for decades. But researchers have now learned that the giant Pacific octopus (GPO)—the largest known octopus on Earth, ranging from California to Alaska to Japan—is actually two species. Now that we’ve been properly introduced to the new “frilled giant octopus,” we’ll need to learn more about it to ensure its survival.

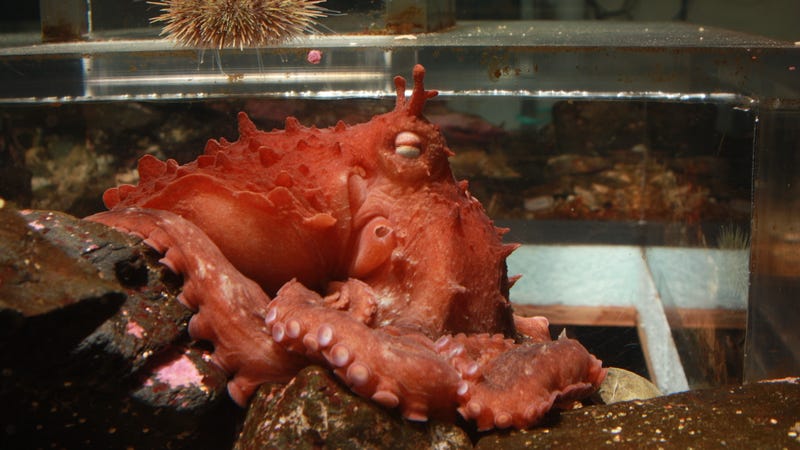

The frilled giant Pacific octopus.

The frilled giant Pacific octopus.

D. Scheel

This discovery isn’t a total surprise. Scientists have suspected for decades that giant Pacific octopus might be an “umbrella name” covering more than one species. In 2012, researchers from Alaska Pacific University and the US Geological Survey found a genetically distinct group of GPOs in Prince William Sound. Unfortunately, they’d collected only small snips of arm tissue for DNA analysis before returning the octopuses to the wild, so they couldn’t find out whether the two groups might be visually distinct as well. So Nathan Hollenbeck, an undergraduate student at Alaska Pacific University, tackled these cryptic creatures for his senior thesis by looking at shrimp fishing bycatch, where the octopuses commonly turn up.

Shrimp fishers in Alaska lower baited pots into the water, let them sit for up to a day, then retrieve them to get the shrimp that have climbed in. Occasionally a giant octopus will climb in too—perhaps interested in the bait, or perhaps simply investigating crevices, as octopuses are wont to do. “Usually the octopuses have eaten the shrimp,” Hollenbeck told Earther, “so there’s a lot of shrimp shells and legs and antennae.”

A regular giant Pacific octopus.

A regular giant Pacific octopus.

Kirt L. Onthank

Hollenbeck quickly found that he could identify two kinds of giant octopus just by looking at them. One was the familiar GPO; the other sported a distinctive frill along the length of its body. These frilled octopuses also exhibited curious “eyelashes” of raised skin, and bore two white spots on the front of the head, where GPOs have only one.

To confirm that the visually distinct group matched the genetically distinct one, Hollenbeck cut off tiny pieces of the octopuses’ arms. And because he wanted to know if future work could avoid this invasive sampling technique, he also collected DNA by swiping the octopuses’ skin with cotton swabs.

You’d probably prefer that a doctor swab your cheek rather than stick a needle in your arm — or snip off the tip of a finger. (At least octopus arms regenerate.) Other animals probably share this preference. Scientists routinely use non-invasive sampling techniques on mammals and birds, but Hollenbeck was the first to try swabbing an octopus. It worked like a charm, and DNA from arm tips and swabs agreed: the frilled octopus is a separate species from the GPO. Hollenbeck and his advisor David Scheel published their results in November in the American Malacological Bulletin.

“Presumably, people have been catching these octopuses for years and no one ever noticed,” Scheel said. Frilled giant octopuses appear to be less widely distributed than GPOs—Hollenbeck and Scheel have collected reliable reports of the species only from Juneau to the Bering Sea. They also seem to prefer deeper water, unfrequented by tidepoolers or scuba divers. In this habitat, though, they might be fairly common. Frilled giants made up a third of octopus bycatch in Hollenbeck’s shrimp pots.

Crab and cod are also fished with pots in the Gulf of Alaska, and it’s likely that many of the octopuses caught in these pots will turn out to be frilled giants, too. No one knows whether that poses a threat to the species’ survival.

Even for GPOs, we don’t have enough information to determine whether they’re at risk of overfishing. Government scientists at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center recommend “very conservative” management “due to the poor state of knowledge of the species composition, life history, distribution, and abundance of octopus” in the Gulf of Alaska.

Frilled giant Pacific octopus.

Frilled giant Pacific octopus.

D. Scheel

For the time being, federal regulations specify a maximum octopus bycatch based on the best available estimates of how many are out there. The Alaska cod fishery has been closed on at least one occasion when it hit this limit. But with GPOs and frilled giants lumped together in bycatch numbers, it’s impossible to distinguish the impacts of fishing on the two different species.

The frilled giant octopus doesn’t have a Latin name yet (though it’s expected to be in the same genus as the GPO, Enteroctopus). Named or not, frilled giants will continue to investigate fishing pots and get hauled to the surface, where they will sometimes be thrown back in the water and sometimes killed to use as bait. In either case, they will be recorded as just another giant octopus, indistinct from the GPO.

And yet the skin-deep differences between the two species may represent any number of more fundamental differences in lifestyle, diet, or reproduction. About the frill, Scheel said, “I’ve been thinking: why would an octopus have a ledge coming off its body like that? Maybe we’re seeing differences in their habitat selection and ecology reflected by differences in their body.” He’s interested in comparing the giant species to smaller octopuses that also sport frills, to look for patterns in habitat use.

For now, we know little more than these admiring words of Scheel’s about the new giants: “They’re so pretty.”

Danna Staaf is a freelance science writer, author of Squid Empire: The Rise and Fall of the Cephalopods, and followable on Twitter.

=============================

by Danna Staaf

There may be links in the Original Article that have not been reproduced here.

octo-π

looks like the Horta from Star Trek