The Fed Is Targeting the Wrong Inflation

Consumers are increasingly asking: Is this a need or a want? A discernible gap between the rate of price increases for necessities and the one for discretionary purchases is putting the Federal Reserve’s tightening path at risk of veering off course.

Making matters more difficult, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge does a pitiful job of capturing the quandary facing many households that live paycheck to paycheck. The so-called core PCE is the central bank's go-to inflation metric. It is derived by netting out the necessities of food and energy from personal consumption expenditures. But the core PCE also minimizes the weight of rent and over-emphasizes health care due to Medicaid and Medicare’s inputs.

They're buying stuff -- for now.

They're buying stuff -- for now.

Doreen Spooner/Keystone Features/Getty Images

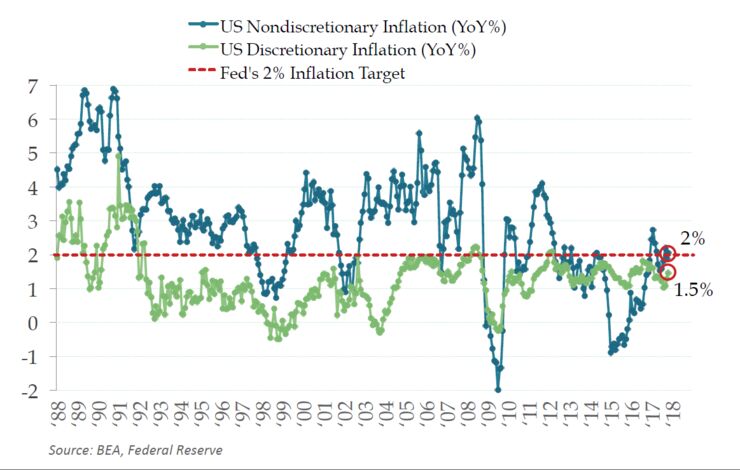

Classify the following items within the core PCE as necessities and then track them as an aggregate using what we can call the Household Budget Inflation Gauge. Included are food and nonalcoholic beverages, fuels, clothing, housing, utilities, health care, health insurance, homeowners’ insurance, auto insurance, higher education and the phone, utility and internet bills. As of the latest reading, these costs are rising at a 2 percent rate compared with last year.

Now throw all of the rest of the discretionary items into what we can call the Household Wish List Inflation Gauge and you will see that these items’ prices have been rising at a pace of 1.5 percent.

Yet if you insist on comingling these baskets and then throwing out food and energy, you will by flying as blindly as the most dovish members of the Federal Open Market Committee. Consider these recent comments from Chicago Fed President Charles Evans, who rotated off voting on the FOMC after last December’s meeting:

"I’d feel a lot more confident if I saw those transitory reductions in the inflation rate go away,” he said. “And if in fact things are worked out we could resume a nice gradual pace (of rate hikes) at that point, and still get the funds rate up to its natural level before too long."

Evans added that the opportunity cost of waiting until the middle of the year carried little risk. The catch in his thinking is that the recent rise in oil prices promises to filter through to higher prices at the gas pump.

In other words, six months from now the gap between the growth of discretionary and non-discretionary inflation should be wider than today’s half-percentage-point. That could be a problem. Evans is correct to express caution about the Fed’s expected tightening path; not because inflation is too low, but rather because the inflation that matters most to households is too high and poised to rise further.

For the moment, the media is captivated by news of bonuses as companies pay forward the expected fruits of the tax cuts. But not all of the news in the New Year has been employee-friendly. In an echo of last January, struggling retailers are announcing store closures that will result in pink slips. And that’s if the employees are lucky enough to receive notice.

Wal-Mart surprised markets with the abrupt announcement this month that it would close 63 Sam’s Club stores. In an act of savvy PR, the mega-retailer combined the closure news with the announcement of a higher starting salary for new employees and bonus payments.

The question economists and Fed policy makers must try to answer as the year progresses is what households that get raises or one-time bumps to their incomes will do with the proceeds. Will they pay down debts or spend the money?

As Van Hoisington and Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Asset Management said in their fourth-quarter review and outlook, history suggests it is highly unlikely that households will continue to spend as they have recently. Had consumers not whittled down their savings by half in the past two years through November, spending would have risen at a 1.5 percent annual rate instead of the 2.8 percent rate that was reported.

“An increase in consumer credit of $253 billion and an actual reduction in savings of $190 billion account for this difference,” Hunt and Hoisington wrote. “It is possible that the saving rate will continue to fall. A drop of the same magnitude in the next 25 months would mean the saving rate would be -0.1 percent, a possible yet unlikely scenario.”

Think of what U.S. households are experiencing as akin to when a company withstands a margin squeeze. In the beginning, firms try to raise prices. A lack of pricing power, however, forces companies to borrow to cover higher costs. If higher demand does not materialize, however, cost-cutting measures must be undertaken. Something always has to give.

The same can be said of households. If they do not have the ability to demand appreciably higher wages, or worse, lose their source of income altogether, something will also have to give. If the past tells us one thing about a saving rate that dips below the 3 percent threshold, it is that reduced spending is not too far behind.

=============================

by Danielle DiMartino Booth

There may be links in the Original Article that have not been reproduced here.

Tags

Who is online

62 visitors

Interesting reflection on yardsticks...

I was a management consultant for many years. One of the cardinal sins for a manager is picking an inappropriate yardstick for performance. People work for the yardstick, so it had better be conform to the real objextive