For Gibraltar the EU was an escape hatch. No longer

In the streets of Gibraltar, 30 years ago last Tuesday, soldiers of the SAS regiment shot dead three members of the IRA. Early reports explained the killings by the presence of a car bomb that the three had placed outside the governor’s residence; according to the ITN bulletin that night, the three had died in a “fierce gun battle”, and their bomb was destroyed by a controlled explosion. The next day the bomb appeared more hypothetically in news reports. As the foreign secretary explained to the House of Commons: “Had a bomb exploded in the area the casualties could well have run into three figures.” Eventually it emerged that there had been no bomb in Gibraltar and no gun battle. In September, an inquest began to determine whether the killings had been lawful, and I went out to attend the hearings.

Illustration: Matt Kenyon

Illustration: Matt Kenyon

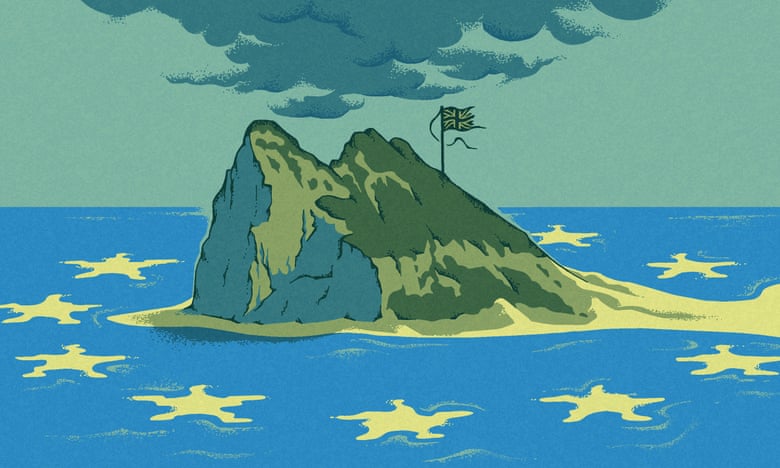

I had never been to Gibraltar before that summer, but I knew it as an idea: it was one of those odd bits of the imperial story that even in the 1950s could still lodge itself in a child’s mind. It was a British military base, a fort and a sentinel. Most of all it was a rock. Rock-like, solid and everlasting: “as safe as the Rock of Gibraltar”, people said, sometimes adding that so long as its famous population of Barbary apes (in fact, Moroccan macaques) endured, so would British rule. Gibraltar, not Calais, was the first glimpse of the European mainland for generations of British and Irish soldiers and settlers, including several of my ancestors, who shipped out to the colonies through the Mediterranean and the Suez canal and sent home postcards from their calling points (after Gib came Malta, Port Said and Aden). Before the first world war redirected young men towards France, it was this further world that called them.

The colony’s British atmosphere, therefore, came as no surprise. Its newsagents sold the Sun and Silk Cut; Mac’s Fish Bar fried cod and chips; and off-duty soldiers drank lager in pubs with names such as the Angry Friar and the Olde Rock. At night the streets rang to the shouting and singing of a typical garrison town. And over it all, on most days I was there, hung the cloud known as the Levanter, a consequence of a moisture-laden east wind rushing across the Med, hitting the rock’s steep face and there shooting upwards to vaporise. The day-long shade meant that, even in respect of climate, Gibraltar differed from the country that lay just across the bay.

The importance of this difference to Gibraltarians was less expected. In the centuries since 1713, when the treaty of Utrecht awarded it to Britain, the colony had developed its own singular character, with a migrant population drawn from Spain, Genoa, Malta and Morocco, as well as civil servants from Britain and traders from India. But what Gibraltarians were not like seemed more important to them. In 1988 I wrote that “their whole identity is antithetical; to be Gibraltarian is not to be Spanish; to be free is not to be Spanish. Therefore to be free and Gibraltarian is to be British, because Britain is all that stands between them and a successful Spanish reclamation of their rock.”

There were some odd consequences. Spain was only a mile from the town centre, but Gibraltar’s bread came frozen in lorries from Bristol. Spanish was the colony’s first language, but no Spanish newspapers could be found – on the counter no El País sat snugly with the Daily Telegraph – and the local radio and television stations broadcast only in English. General Franco died in 1975, but 13 years later Gibraltarians still viewed Spain as a country of secret policemen, sinister priests and tyrannical bureaucrats ruling a population who, a Gibraltar politician told me, “don’t understand freedom as we do”.

The antipathy towards Spain was understandable – it had troubled Gibraltar with sieges and blockades almost since the day Britain moved in – but the colony’s own version of freedom also had its limits. One day, trying to pinpoint the exact location of the shootings, I tried to buy a map – one that marked more than the hotels and the feeding sites of the macaques. A woman in the town’s only bookshop said that ordnance survey maps weren’t available to members of the public, which was incredible. Someone suggested the public works department. When I went there a helpful draughtsman showed me a splendid array of maps, but his superior, discovering I was a reporter, made several telephone calls and said eventually: “I am sorry but the attorney general has refused me permission to sell you a map.”

Naturally, the colony was nervous. More became known. Though there was no bomb in Gibraltar when the three were shot dead, they were an IRA active-service unit that had one waiting to be transported from Spain, with the band of the Royal Anglian regiment as its intended target. Gibraltar and Belfast now had the IRA in common as well as the British army (which in one of the Rock’s large manmade caverns was said to have built, for training purposes, a mock Northern Irish village made of wood – streets, shops, a school, a church called St Malachy’s and, for some reason, a women’s lavatory).

But they shared other things too. “Free since 1713,” said the graffiti that was daubed on Gibraltar’s walls in the same red, white and blue as “Remember 1690” in loyalist Belfast. And with those dates and causes came a sense of embattlement, which varying degrees of revanchism in Spain and the Irish Republic had helped keep alive, though the truth was that it needed little encouragement. One night, lying half-asleep in my room at the Holiday Inn, I heard an old sectarian song in the street below. A Glasgow song, to the tune of Marching Through Georgia: “Hello, hello, we are the Billy Boys... We’re up to our knees in Fenian blood... Surrender or you’ll die...” I looked down from the window. The singers, unsteady on their feet, were reporters from the tabloid papers. WHY THE DOGS HAD TO DIE had been the Sun’s headline over a recent report from the inquest.

It would be foolish to think the European Union alone brought these conflicts to a close. Nevertheless, for Gibraltar and Northern Ireland – for England itself, if England had the wit to recognise it – the EU offered an escape hatch from an imperial identity. Hard edges have been softened; sovereignty means less; historic anomalies such as Northern Ireland and Gibraltar have an easier time. Gibraltar, which had no future as a military base for a country losing its military strength, makes a better living out of selling car insurance.

Perhaps the newsagent now sells El País. Just 4% of Gibraltarians voted to leave the EU. The will of the people in its old imperial homeland has put it in a very hard spot.

=============================

by Ian Jack

There may be links in the Original Article that have not been reproduced here.

Brexit is insane:

A hasty decision taken through a foolishly simplistic process, for motives that were dubious at best, without measuring the negative consequences.

Scotland is again making noises about independence. The Irish border is an insoluble problem. And Gibraltar, British for more years than it was ever Spanish, will be abandoned. These are all solid "Remain" voters, but they were ignored.

Bravo, England!