What we say vs what we mean: what is conversational implicature?

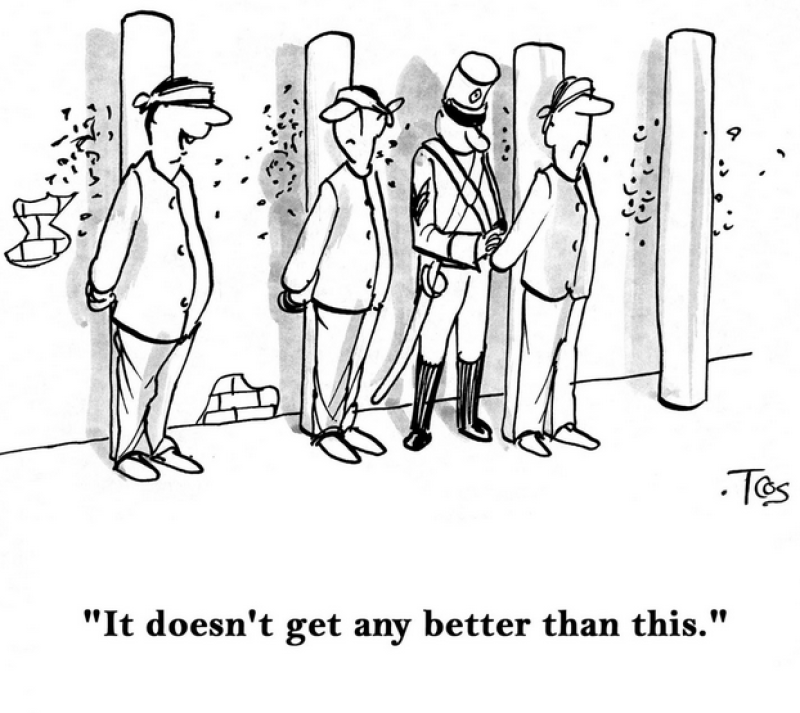

Imagine you have been asked to review the reference letters provided by the candidates for a lectureship in philosophy. One reads: ‘My former student, Dr Jack Smith, is polite, punctual and friendly. Yours faithfully, Professor Jill Jones.’ You would, I assume, interpret that Jones is implying that Smith is a bad philosopher and unsuitable for the job. But how did she convey this? By what she left out. Jones does not say (literally) that Smith is a poor philosopher. Nor does it follow logically from what she says. It could be true that Smith is polite, punctual, friendly and an excellent philosopher. Yet somehow Jones gets the opposite message across.

When we convey a message indirectly like this, linguists say that we implicate the meaning, and they refer to the meaning implicated as an implicature. These terms were coined by the British philosopher Paul Grice (1913-88), who proposed an influential account of implicature in his classic paper ‘Logic and Conversation’ (1975), reprinted in his book Studies in the Way of Words (1989). Grice distinguished several forms of implicature, the most important being conversational implicature. A conversational implicature, Grice held, depends, not on the meaning of the words employed (their semantics), but on the way that the words are used and interpreted (their pragmatics).

Grice argued that conversational implicatures arise because speakers are expected to be cooperative – to make contributions appropriate to the purpose of the conversation in which they are engaged. More specifically, they are expected to follow four conversational maxims, which can be summarised as: (1) give an appropriate amount of information (the maxim of quantity); (2) give correct information (the maxim of quality); (3) give relevant information (the maxim of relation); and (4) give information clearly (the maxim of manner). According to Grice, a conversational implicature is generated when an utterance flouts one or more of these maxims, or would do so if the implicature weren’t present. In such cases, we can preserve the assumption that the speaker is being cooperative only by interpreting their utterance as conveying something other than, or additional to, its literal meaning, and this is its implicated meaning.

Jones’s letter is an example. Since she bothered to write it, we assume that Jones is trying to make a cooperative contribution. But the information she gives is obviously insufficient, flouting the maxim of quantity. Hence, we infer that she is trying to convey something else, which she doesn’t wish to say directly, and the obvious conclusion is that what she’s trying to convey is that Smith is unsuitable for the job. (The example is adapted from one of Grice’s own.) For other examples, think of saying: ‘That’s a nice way to behave’ (flouting quality) to convey that someone behaved badly; pointedly changing the subject (flouting relation) to convey that a remark was tasteless; or describing something in an unusual way (violating manner) to convey that it is unusual in some way (eg, calling a broken-down horse a ‘steed’).

...

The distinction between what is said and what is conversationally implicated isn’t just a technical philosophical one. It highlights the extent to which human communication is pragmatic and non-literal. We routinely rely on conversational implicature to supplement and enrich our utterances, thus saving time and providing a discreet way of conveying sensitive information. But this convenience also creates ethical and legal problems. Are we responsible for what we implicate as well as for what we actually say?

Extract from the Original article by Maria Kasmirli , in aeon .

We generally presume that a person who says/writes something is attempting to communicate an idea. As this article illustrates, the intended message may be expressed directly, or intimated, ... or even expressed by its polar opposite.

Here on NT, we find all those possibilities, and additionally the possibility that the writer is willfully expressing an idea they know to be false.