What happened to winter? Vanishing ice convulses Alaskans' way of life

Arctic Dispatches, part 1: The past winter was the warmest on record in the Arctic, putting a lifestyle that has endured for millennia at risk: ‘The magnitude of change is utterly unprecedented’

A few days before Christmas last year, Harry Brower, mayor of Alaska’s North Slope Borough, was at home when he heard a stunning noise – the sound of waves lapping at the shore.

The sound was as wrenching and misplaced as hearing hailstones thud into the Sahara. Until fairly recently, the Arctic ocean regularly froze up hard up against the far north coast of Alaska by October. In 2017, it wasn’t until the final few days of the year that the ice encased the waves.

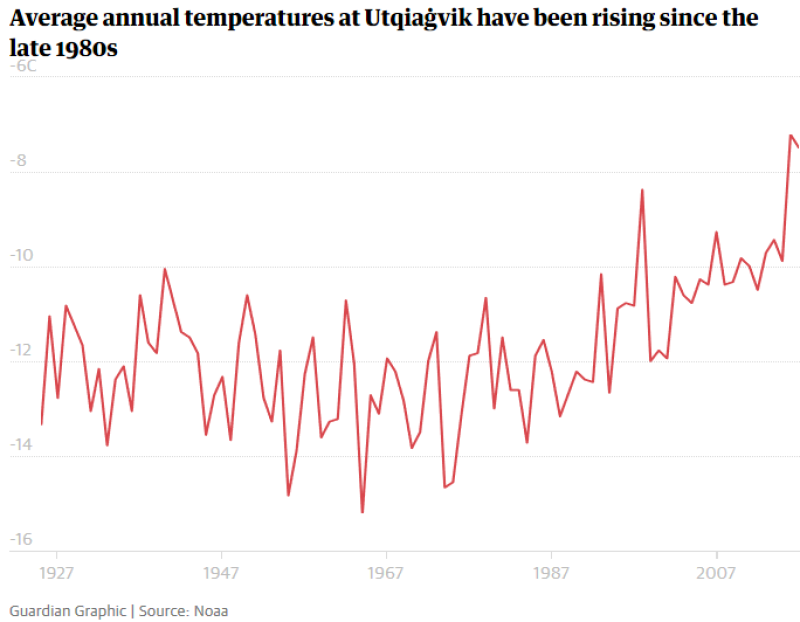

“We’ve had a few warmer days in the past but there was nothing like the past winter,” said Anne Jensen, an anthropologist who has worked in Utqia?vik, the US’s most northerly town, for the past three decades. It was so warm that the snow melted on Jensen’s roof, causing it to leak.

“This year’s winter stuck out, insanely. It was crazy. Even the younger people noticed that this is something that hasn’t happened before.”

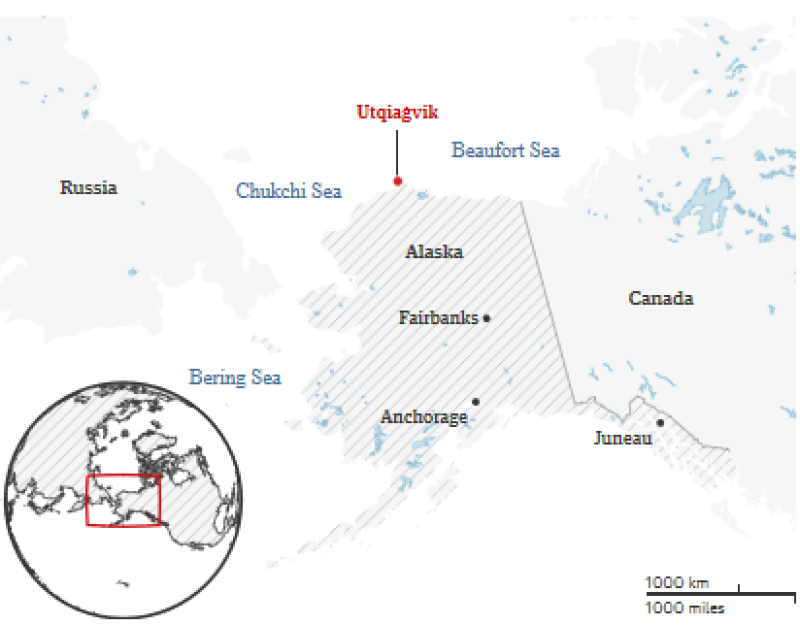

Utqiaġvik, formerly known as Barrow, is the largest of the region’s scattered settlements and remains a flinty and unforgiving frontier town despite the arrival of the internet, buzzy snowmobiles and exotic vegetables (a pineapple costs around $9.50 (£6.70) at the main grocery store).

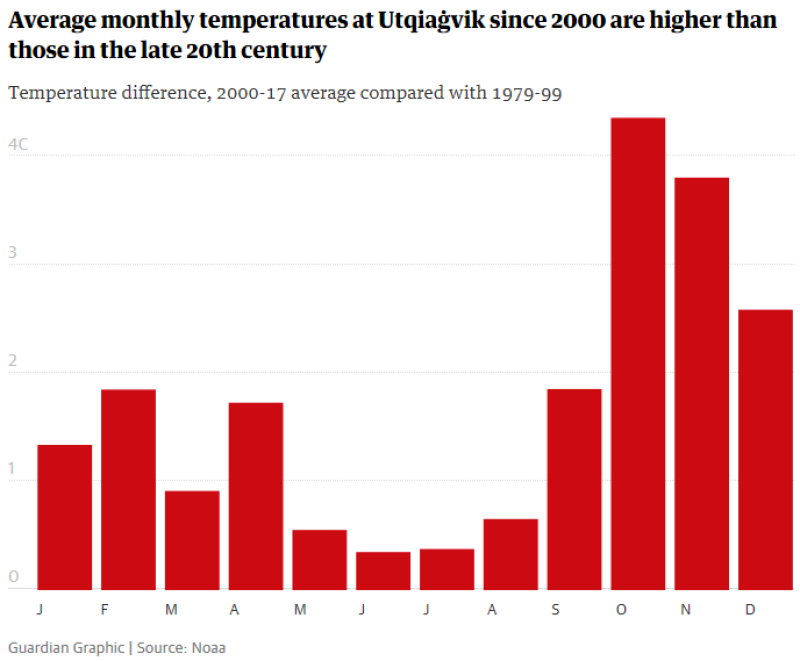

But the past winter, following a string of warm years, points to a pace of change not before experienced by this community. The winter was the warmest on record in the Arctic, with sea ice extent hitting record lows in January and February, ending up at the second-smallest seasonal peak in the 39-year satellite record in March. The smallest was in 2017. The Bering Sea, which separates Alaska and Russia, lost a third of its winter ice in just eight February days.

Otherworldly temperatures were felt across the region, with the weather station closest to the North Pole spending more than 60 hours above freezing in February, around 25C (45F) warmer than normal, which is equivalent to Washington DC spending a February day at 35C (95F) or Miami baking at 51C (124F). The Arctic was, in spells, warmer than much of Europe.

Arctic spring is starting 16 days earlier than a decade ago, study shows

Read more

Utqiaġvik, pronounced oot-ki-ahh-vik or “place where snowy owls are hunted”, got to -1C, around 22C warmer than normal. In December, the temperature readings from the weather station at Utqia?vik were so freakish that it triggered an automatic shutdown of the system to protect the data from “artificial” figures. It temporarily wiped a year’s worth of numbers.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration called the incident an “ironic exclamation point” to the climate change gripping the Arctic, which is warming at twice the rate of the global average. This winter’s extreme warmth was, in part, driven by an unusual number of storms in the Atlantic that brought balmier air to the Arctic. But scientists warned that 2017 and 2018 should not be dismissed as mere outliers.

“There’s no reason why this sort of warmth won’t continue. Within the lifetime of middle-aged adults, the Arctic has completely changed,” said Rick Thoman, a Noaa climate scientist based in Fairbanks, Alaska. “The magnitude of change is utterly unprecedented. For a lot of the people who live there, it’s completely shocking.”

Sign up to the Green Light email to get the planet's most important stories

Read more

The changes are potentially existential on the north slope, where sea ice provides a crucial platform for catching and hauling in whales – a key food source and cultural totem for the Iñupiat. The spring whale hunt, where emerging cracks, or “leads”, in the sea ice funnel whales into the path of waiting hunting crews, requires dependable environmental cycles that have served the Iñupiat for thousands of years.

“All the indications are there will be a very early loss of ice this year,” Thoman said. “In the 1990s they could do whale hunting in Utqia?vik up until May or even June. There’s no real chance of that now – the ice will probably start breaking up by early May.

“Native peoples of Alaska are very resilient; they’ve lived here for many millennia for a reason. Some will have to move, hunting will have to change. It can be done but it won’t be easy, it won’t be cheap. There will be a big cost, both financially and culturally.”

Utqiaġvik is wrestling with a number of climate impacts. Its coastline, increasingly shorn of sea ice, is eroding at a concerning rate. The melting of permafrost, long-frozen soils that scientists forecast could end up releasing huge amounts of carbon, is causing some buildings to slump, their walls radiating with cracks.

Advertisement

But it’s the potential threat to the whale quota that causes most angst. Slain whales need to be quickly pulled up on to the sea ice and butchered before the cetaceans’ cooling systems halt and they essentially cook from within. Lack of thick, multi-year ice could hinder the haul-out. Caught whales could even fall through the ice if it’s too thin.

“A couple of years ago the ice was rubble, it was just breaking up,” said Nagruk Harcharek, who has spent many of his 33 years whaling near Utqiaġvik. “It was really late this year and everyone noticed. I’d be lying if I said people aren’t worried.

“Some families rely upon whales for their food. It’s so central to our culture. The spring hunt is spiritual – sitting out there on the ice edge is pretty quiet. There’s the unknown. There’s not much going on. You’re watching, waiting.”

Other heritage is already being lost, with archaeological sites along the coast being washed away at a quickening rate. In September, a major storm crunched into the coast and threatened Birnirk, a village that was inhabited for 1,000 years and is a national historic landmark.

“It’s very, very grim,” said Jensen, who has worked to excavate and protect several sites. “Most of the coastal sites will be gone in the next 10 to 15 years if the rate of erosion keeps up.”

Arctic warming: scientists alarmed by 'crazy' temperature rises

Read more

Across Alaska, dozens of coastal towns are at risk of becoming uninhabitable, with a handful actively seeking to relocate. Melting permafrost is buckling roads into potentially deadly big dipper rollercoasters, as well as threatening to dislodge doses of locked-up mercury. Glaciers near Denali, the tallest mountain in the US, are disappearing faster than at any time in the past 400 years.

The Alaskan government recently warned this bewildering rate of change risks the physical and mental health of its citizens, citing a condition called solastalgia, the distress caused by severe disruption to the environment near home.

“Alaska is on the frontlines of climate change,” Bill Walker, the state’s governor, warned last year. Walker, an independent, has convened a panel to come up with some sort of climate change strategy by September.

Somehow, it will have to suggest a way forward that doesn’t rattle its economically important oil and gas industry, which has received staunch support from a Trump administration that has started to dismantle help for those pummeled by rising seas and storms.

For a reliably Republican state, polling shows unusual numbers of Alaskans are concerned about climate change and, at least sometimes, openly fret over its consequences. “People are feeling the impacts of climate change, we hear that on a daily basis,” said Nikoosh Carlo, the governor’s climate adviser. “It’s a non-partisan issue here. For some communities, the next storm could wipe out critical infrastructure.”

The lack of any federal or state plan to deal with the looming climate crisis isn’t causing mass panic in Utqia?vik, at least.

“We are capable of adapting to any changes,” said Charlie Hopson, a veteran Utqiaġvik whaler. “We’ve been around for thousands of years and we’re going to keep living. We do our own thing here. The government doesn’t know shit. We don’t need them.”

Extract from the Original article by Oliver Milman , in The Guardian .

... and there are still Honorable Members of the NewsTalkers who deny the reality of climate change...

"Arctic Dispatches, part 2" coming up, later this morning...

Didn't really have a winter here in the land of OZ. Put off buying new 4X4 AT tires until next winter.

I wonder if the rapidity of change will turn that red state blue?

I don't know if anyone who denies climate change can be considered honerable.

What happened to winter?

Still hanging on here in the Northeast, Bitch won't leave:)

In the Rockies as well. We just got like twenty inches of snow two days ago.

We just got 8" from the same storm in SW WI but it's pretty much all gone now. Despite a stretch of severely cold weather this was pretty much a non-winter.

Right now the Chinese are in full test mode on fusion and expect to have it operational ( ). Fusion is far safer and more efficient than fission and it's wastes decays at a much higher rate and is less dangerous to the environment. Sure I remember the whole Shoreham fiasco. I even knew the engineer that was the whistleblower. Location matters and putting a nuclear plant on a thin long island with no means of escape is kind of nuts. But with fusion there is no chance of a melt down, and that is what makes it so valuable. So to your next question my answer is yes, I do feel that fusion is far different than fission.

That is changing as well. There are car batteries that last and better design. All the Teslas are getting over 250 miles per charge, which is a game changer. The bigger issue is the charging stations, but recently I have seen more popping up.

I said cutting back, not doing away. Beef is the biggest problem. And for the record, we have a lot of vestiges of our past on our bodies, but it doesn't mean we need them anymore. You get wisdom teeth because your back in the day, your molars wore out and you needed replacements. But now, for most people, they are removed, since the old molars are still there and viable.

I asked my question first and you have not replied. I will reply and when you do.

And btw.. I will give you the answer that is I feel best answers your question.