America’s cheese stockpile just hit an all-time high

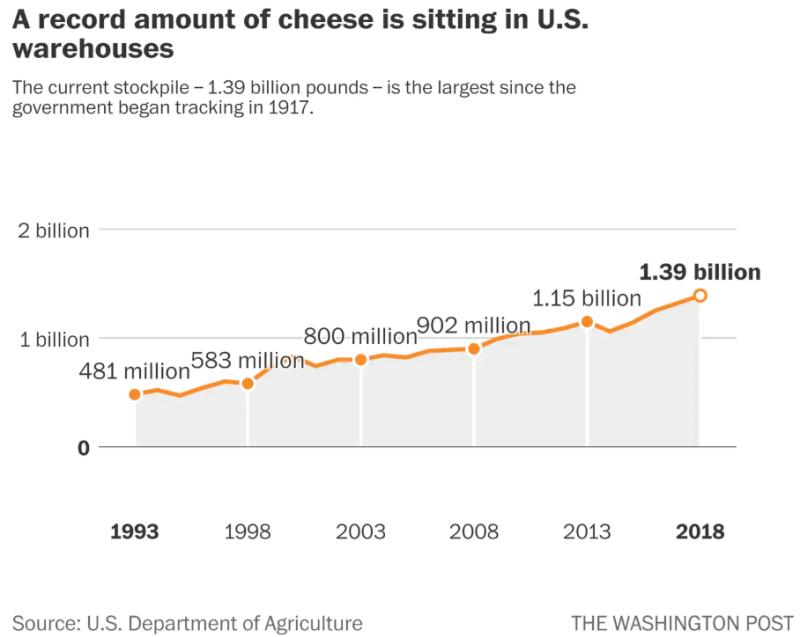

The United States has amassed its largest stockpile of cheese in the 100 years since regulators began keeping tabs, the result of booming domestic production of milk and consumers’ waning interest in the dairy beverage.

The 1.39 billion-pound stockpile, tallied by the Agriculture Department last week, represents a 6 percent increase over this time last year and a 16 percent increase since an earlier surplus prompted a federal cheese buy-up in 2016.

Analysts say commercial warehouse stocks have swelled because processors have too much milk on their hands, and milk is more easily stored as cheese. Demand has also fallen as school cafeterias close for the summer and restaurants wind down the cheesy specials they offer in the winter and early spring.

Some have grown concerned that stockpiles will build further yet if trade tensions with China and Mexico cut into cheese exports. Cheese prices have fallen sharply, they say, eroding dairy farmers’ already thin margins.

“Milk production continues to trend up, and that milk has to find a home,” said Lucas Fuess, director of market intelligence at HighGround Dairy, a consulting firm. “The issue this year is that, with so much supply, it’s going to be tough for a lot of farmers to be profitable.”

Cheese surpluses do tend to grow at this time every year. Cows are at their most productive in the spring, when the days are longer and the feed better. At the same time, Americans typically eat less cheese now than they do during the holidays, the school year and the winter sports season.

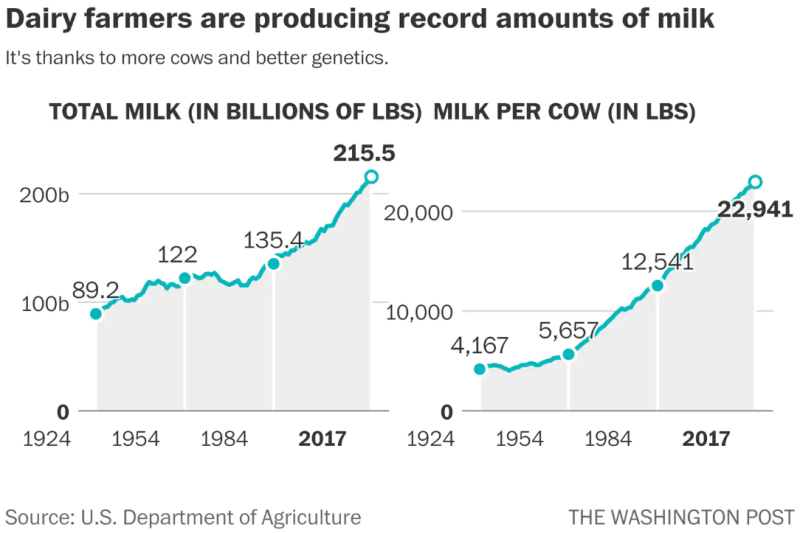

But the summer surpluses are growing larger. Better genetics mean that cows produce more milk, and consolidation means farms keep more cows. Unable to sell that milk in pints or gallons — which Americans are abandoning, also in record numbers — processors plow it into cheese, butter and milk powder.

“I anticipate that we’ll continue to set these records,” said John Newton, director of market intelligence at the American Farm Bureau Federation. “We’re producing more milk. It’s inevitable. That milk needs to get turned into something storable.”

But the sheer amount of cheese in storage may be causing problems. Cheese prices have fallen in recent weeks, Fuess said, a response both to the surplus and to growing trade concerns.

That fall is problematic, said Mark Stephenson, director of dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, because the price of cheese is a major factor in the equation that USDA uses to set the price that dairy farmers receive for their milk. The current price — $15.36 per 100 pounds — is about a dollar below the average for 2017 and well below the price that many farmers say they need to break even.

“When inventories get too large, that pushes the prices down,” he said. “And yes, that trickles down to dairy farmers.”

Dairy groups aren’t yet asking USDA to buy the surplus, however — a common practice that Newton calls “quantitative cheesing.” In 2016, dairy farmers requested that the agency buy more than 90 million pounds of cheese to cut the country’s “mountain” of excess dairy.

Michael Dykes, president of the International Dairy Foods Association, said that although stocks are sky-high, he is confident Americans will eat through them. That's because stock-to-use ratios, a measure of the amount of cheese taken out of storage, have remained constant even at these higher levels.

On top of that, cheesy foods remain a hallmark of the U.S. diet. This current record was driven by a buildup of non-American, non-Swiss cheeses — largely mozzarella, experts suspect — that could get drawn down by strong summer pizza sales.

There's one wrinkle in his calculus, Dykes admits: mounting trade tensions. Last year, the United States exported more than 341,000 metric tons of cheese to countries such as Mexico and China. If those countries turn to Europe for their cheese instead, the U.S. stockpile could grow to crisis levels. Already, USDA has begun documenting those concerns among major cheesemakers.

“One milking day a week goes to the export market,” Dykes said. “There's a lot of uncertainty now. I don't think we really know what will happen yet.”

Tags

Who is online

54 visitors

No problem!

We'll just export the excess... to Europe!

... euh...

Ok, then... to China!

... ... ummm...