From Dow’s ‘Dioxin Lawyer’ to Trump’s Choice to Run Superfund

The lawyer nominated to run the Superfund toxic cleanup program is steeped in the complexities of restoring polluted rivers and chemical dumps. He spent more than a decade on one of the nation’s most extensive cleanups, one involving Dow Chemical’s sprawling headquarters in Midland, Mich.

But while he led Dow’s legal strategy there, the chemical giant was accused by regulators, and in one case a Dow engineer, of submitting disputed data, misrepresenting scientific evidence and delaying cleanup, according to internal documents and court records as well as interviews with more than a dozen people involved in the project.

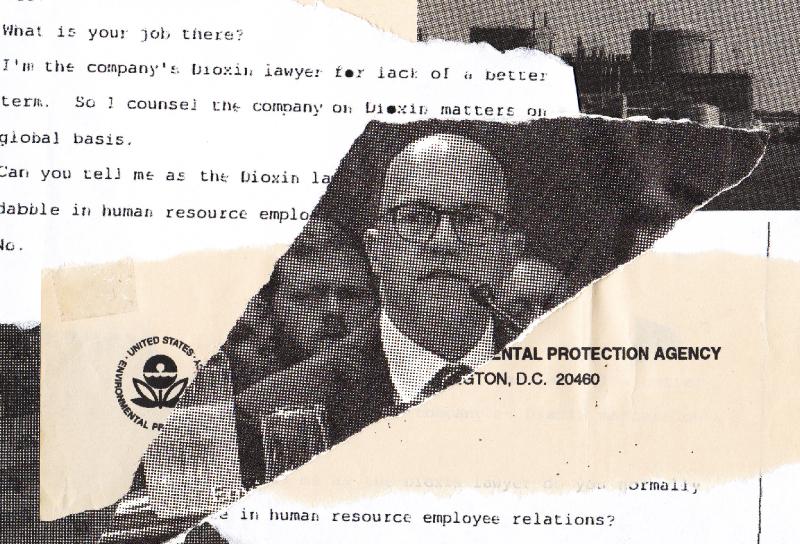

The lawyer, Peter C. Wright, was nominated in March by President Trump to be assistant administrator at the Environmental Protection Agency overseeing the Superfund program, which was created decades ago to clean up the nation’s most hazardous toxic waste sites. He is already working at the agency in an advisory role as he awaits congressional approval. If confirmed, Mr. Wright would also oversee the emergency response to chemical spills and other hazardous releases nationwide.

E.P.A. officials pointed to Mr. Wright’s expertise in environmental law and his tenure at Dow as valuable qualifications. The White House on Saturday referred questions to the E.P.A.

He spent 19 years at Dow, one of the world’s largest chemical makers, and once described himself in a court deposition as “the company’s dioxin lawyer.” He was assigned to the Midland cleanup in 2003, and later became a lead negotiator in talks with the E.P.A. It was during his work on the cleanup that the agency criticized Dow for the cleanup delays, testing lapses and other missteps.

Laura McDermott for The New York Times

For more than a century, the Dow complex manufactured a range of products including Saran wrap, Styrofoam, Agent Orange and mustard gas. Over time, Dow released effluents into the Tittabawassee River, leading to dioxin contamination stretching more than 50 miles along the Tittabawassee and Saginaw Rivers and into Lake Huron.

Dow, which merged with rival DuPont last year, is among the companies most affected by Superfund cleanups nationwide, E.P.A. data shows. The combined company is listed as potentially having responsibility in almost 14 percent of sites on the E.P.A.’s list of priority Superfund cleanups, or 171 locations nationwide.

Mr. Wright has pledged to recuse himself from cleanups related to his former employer, a move welcomed by even one of the administration’s congressional critics.

Still, his appointment “raises all kinds of red flags, and it makes his job more difficult in the sense that he will be watched every second,” said Christine Todd Whitman, who led the E.P.A. under President George W. Bush and who has criticized the agency under the Trump administration.

In recent months, the E.P.A. under its former chief, Scott Pruitt, has been beset by ethics investigations, and an earlier choice to run the Superfund program, a former banker with no experience in toxic cleanups, ultimately resigned. Mr. Pruitt himself stepped down this month, having launched major regulatory rollbacks at the E.P.A. while striking an industry-friendly stance that his successor, Andrew Wheeler, is expected to continue.

Dow finally came to terms with the E.P.A. in 2010, during the Obama presidency, and a cleanup is underway that cost Dow $24 million last year. “Peter was notable for his professionalism, candor, cordiality and grace under pressure,” said Leverett Nelson, an E.P.A. regional counsel who worked with Mr. Wright on that agreement.

E.P.A. officials also stressed that Mr. Wright’s recusal wouldn’t restrict him in the job, since he would still be able to work on the vast majority of Superfund sites. They also credited Mr. Wright with helping to hammer out the eventual cleanup agreement in Michigan.

In a statement, a Dow spokeswoman, Rachelle Schikorra, described Mr. Wright as “a highly skilled and conscientious attorney who provided valuable guidance to Dow on environmental compliance matters for almost 20 years.” She said Mr. Wright retired last month and the company had no role in his nomination. Mr. Wright referred all questions to the E.P.A.

Sammy Jo Hester/Mlive

Biggest Accomplishment

The Superfund program began in 1980 as an ambitious effort to fix thousands of toxic sites — factories, chemical dumps, abandoned mines — left scattered across the American landscape in the age of industrialization. It grapples with profound complexities: Companies disappear or change hands, and the science on toxicity and cleanup methods is often contested, making progress contentious and uncertain.

Mr. Wright, who was on a high-level team at Dow negotiating the Midland cleanup, has pointed to his work on the site as his biggest accomplishment. In a 2017 email to the E.P.A.’s chief of staff, made public last month as part of an environmental group’s lawsuit, Mr. Wright called it “the most controversial matter and the single most publicly successful matter that I have worked on at Dow.”

But the progress came after years of pushback.

In one instance, in 2006, an independent testing company hired to validate Dow’s data on contamination levels rejected the numbers over incomplete information, which increased the risk of “false negatives” that might leave contaminants undetected, according to a deposition given by a technician at the lab in 2008.

The E.P.A. also said in an August 2007 memo that “Dow has frequently provided information to the public that contradicts agency positions, and generally accepted scientific information.” A Dow newsletter mailed to residents in 2004 stated that few health effects were associated with dioxin exposure, citing a health study of Dow workers that the E.P.A. took issue with.

During the years Mr. Wright helped lead the Midland negotiations, the E.P.A. criticized Dow for its slow cleanup. “E.P.A. is concerned with Dow’s lack of progress in addressing the significantly elevated levels of dioxin and furan contamination in the Saginaw Bay watershed,” a separate June 2007 E.P.A. memo stated, referring to two groups of chemicals.

Ms. Schikorra maintained that there was no scientific consensus that dioxin caused adverse health effects in people at today’s environmental levels. She declined to comment on the specifics of the E.P.A.’s other complaints.

Mr. Wright has supporters beyond Dow. A group of environmental lawyers at the American Bar Association, where Mr. Wright was an active member, cited his “well-recognized personal integrity” as exemplifying “the highest standards of the legal profession” in a letter of support sent to the E.P.A. in February.

Along the Tittabawassee River, there was disbelief among some residents that a Dow lawyer who worked on the Midland cleanup was set to take over the Superfund program. “It’s nuts,” said Joel Tanner, a Saginaw resident who is a member of a community group set up by the E.P.A. that advises the cleanup. “Dow are the ones who fought it all the way.”

Laura McDermott for The New York Times

Negotiating the Cleanup

The banks of the Tittabawassee have been home to Dow for decades. Internal documents have suggested that Dow was aware of dioxin’s risks as early as the mid-1960s. In the 1980s, Dow pressured the E.P.A. to change a report that had linked dioxin contamination to Dow’s Midland complex, according to testimony later given by agency officials.

Mr. Wright went to Wabash College in Indiana before graduating from law school at Indiana University. He worked as an environmental lawyer, including seven years at the agrochemical giant Monsanto, before joining Dow in 1999, according to his LinkedIn page. He was assigned to the Midland cleanup in 2003, the year after Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality alerted residents to “the presence of significant concentrations of dioxin” in local soil.

Conflicts with the E.P.A. began early.

In 2004 and 2005, state and federal officials discovered Dow contractors collecting soil samples in the local watershed without telling regulators, which violated a Dow license, according to documents released to a local environmental group, Lone Tree Council, under the Freedom of Information Act. The unauthorized sampling not only prevented regulators from verifying Dow’s results, officials said, but could enable Dow to identify hot spots — high contamination areas — in order to downplay them when designing cleanup plans.

Mr. Wright was one of two Dow representatives on a May 2005 phone call with the E.P.A. and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality instructing the company to abide by the rules. Later, Michigan fined Dow $70,000 for the unauthorized sampling.

Around that time, the E.P.A. became concerned that Dow was presenting misleading scientific evidence. In a memo, it expressed concern over Dow’s newsletter to residents at the time, as well as statements by Dow that wild game — deer, turkey, squirrel — was safe to eat, despite a Dow study showing elevated levels of dioxin in the animals. Michigan’s health department warned people of the risks of eating the meat.

In 2005, Mr. Wright separately wrote about dioxin risk in a legal journal. His article, which appeared in an American Bar Association publication, described dioxin as “highly toxic to a variety of animal species but not to humans.”

In an email, Linda Birnbaum, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, disputed that assertion, saying “it ignores much of what was known and generally accepted by 2005.” The World Health Organization has identified dioxins as carcinogenic to humans, and also links them to reproductive and developmental problems, as well as damage to the immune system.

Mr. Wright also participated in a May 2006 meeting with researchers and regulators about a Dow-funded study at the University of Michigan that eventually found that living on dioxin-contaminated soil was not associated with higher dioxin levels in the body. E.P.A. officials said they believed the study “was initiated at the request of Dow in order to downplay the risks of exposure,” according to an August 2007 memo.

Dow provided a grant of more than $15 million to conduct the study, Ms. Schikorra confirmed. She said Dow was not involved in any aspect of the study.

Laura McDermott for The New York Times

A Dispute Over Data

Dow’s problems with the independent lab testing company started in 2006.

That year, Priscilla Denney, a senior environmental engineer on Mr. Wright’s team, warned Dow that the company, hired to validate its testing of contaminants, had rejected the company’s data, according to a whistle-blower lawsuit she later filed against the company.

The lab, Project Enhancement Corporation, ended its contract with Dow, citing a “breakdown” in the testing procedure, according to the termination letter it sent to Dow.

In Ms. Denney’s whistle-blower suit, she claimed that the way Dow was submitting data to outside labs for validation had been changed while she was on maternity leave, making it impossible for a third party to check Dow’s results, particularly those that showed no levels of contamination.

But her concerns about Dow’s data were ignored and she was demoted in retaliation, she said. A local court later dismissed the case, saying in part that she did not have standing to sue because she had not reported her concerns outside the company.

The company said at the time that Ms. Denney was wrong and that she had not been demoted. Mr. Wright, in a deposition, said he helped investigate Ms. Denney’s concerns.

Documents show Dow submitted the data to regulators in February 2007 without mentioning the lab dispute. That December, the E.P.A. asked for information on the data dispute, according to emails. A few weeks later, it temporarily broke off negotiations. Mr. Nelson of the E.P.A. said this week that he did not recall Ms. Denney’s concerns affecting the talks.

Ultimately, Mr. Wright’s team reached a cleanup agreement with the E.P.A. in 2010. River decontamination is progressing, although officials cannot yet say when it will be complete.

“The bottom line is that after 35 years, there’s still a mess that needs to be cleaned up,” said Dave Dempsey, an environmental activist who was an adviser in the 1980s to then-Gov. James Blanchard. “Dow has been effective in playing the game.”

Laura McDermott for The New York Times

The Legacy in Michigan

As Mr. Wright moves toward a new job in the nation’s capital, he leaves behind a legacy in Michigan.

Today, a picnic bench sits near a stretch of waterfront that was once the site of the highest levels of dioxin contamination found downstream from Dow — 1.6 million parts per trillion, or 1,600 times a federal cleanup standard. Dow has pushed ahead with the cleanup, stabilizing the banks, dredging the river bed and capping contaminated sections with concrete.

Still, there are reminders of the risks. Signs posted along the water warn, “Some fish in the Tittabawassee River have harmful amounts of chemicals.”

“I don’t eat anything I catch,” said Travis Maxson, a restaurant worker who was fishing for bass one weekday from a grassy bank.

Some residents carry with them a lifetime of doubt about choices they made. Alice Buchalter, a virologist-turned-gymnastics coach, settled with her husband on the Tittabawassee a half-century ago. “We thought that we had moved to paradise,” she said.

Laura McDermott for The New York Times

Soon after his 70th birthday in 2004, her husband, a physician, was diagnosed with colon cancer. He died just four months later. Shortly before his death, elevated levels of dioxin were found in his blood.

With her background in science, Ms. Buchalter knows it is difficult to link any single case of cancer to a specific cause, and the American Cancer Society maintains that studies have not found a clear link between dioxin and the cancer that killed her husband.

Still, she said, “Maybe we should have been smarter about living three miles down the river from a chemical plant.”

Hiroko Tabuchi is a climate reporter. She joined The Times in 2008, and was part of the team awarded the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. She previously wrote about Japanese economics, business and technology from Tokyo.

Tags

Who is online

49 visitors