The job Americans won't take: Arizona looks to Philippines to fill teacher shortage

The need for mathematics, science, and special education teachers is especially dire in poor and rural schools.

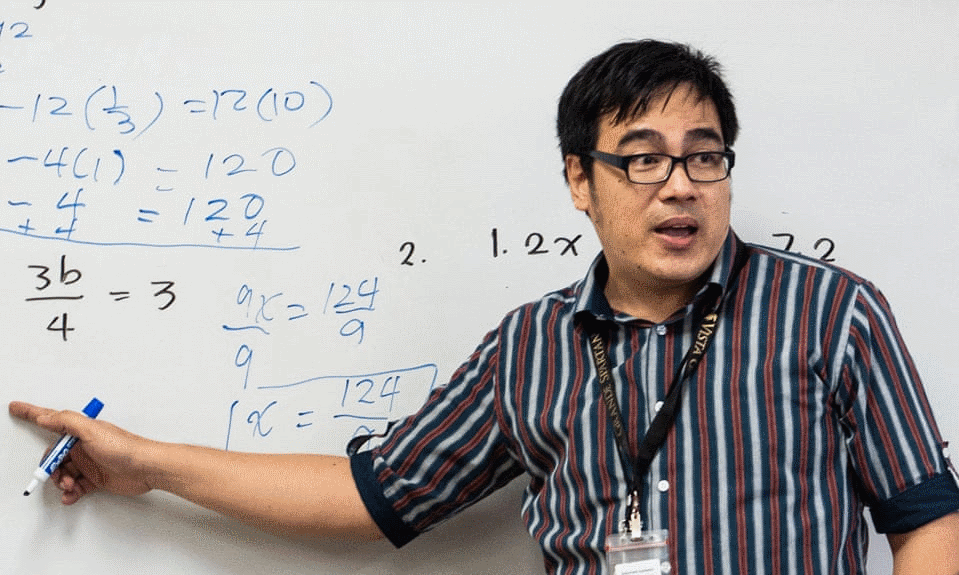

Nick Oza for Guardian US

College-educated Americans are increasingly uninterested in teaching jobs – so Arizona has begun to recruit from abroad.

O n a recent sweltering morning in a public high school in a dusty town in the central Arizona desert, students in an advanced physics class hovered over beakers and flame-testing dishes.

With each experiment, Melvin Inojosa, 29, dressed in teacherly khakis and a bright blue collared golf shirt, bounded between lab tables, sinks, a whiteboard and his desk, exclaiming “Optics!” “Quantum mechanics!” “Thermodynamics!”.

After the students completed their experiments, it was Inojosa’s turn.

“If I catch this place on fire, they will send me back to the Philippines ,” he joked as he sprinted to the end of the classroom, away from the 16-year-olds.

He lit ethanol in a large jug and stepped back. The jug remained intact, but the chemical reaction within delighted the students with a brief, thunderous explosion.

Bam!

Inojosa has taught at Vista Grande high school in Casa Grande, Arizona since 2016. As one of several Filipino teachers employed by the local high school district, Inojosa is part of a controversial experiment in American education: bringing in teachers from developing countries to fill a teacher shortage in public schools.

Some American public schools are turning to foreign teachers because Americans with college educations are increasingly uninterested in low-paid, demanding teaching jobs. Many teachers, struggling for a toehold in the shrinking middle class, have switched careers. And fewer college students are choosing to become teachers. The need for mathematics, science, and special education teachers is especially dire in poor and rural schools throughout the country.

“Teaching has become a much less attractive profession,” said Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute, an education policy thinktank, noting that American teacher salaries have fallen far behind those of other college educated workers.

Joe Thomas, president of the Arizona Education Association, a teachers’ union, said uncompetitive teachers’ salaries have forced school administrators to look for “creative ways” to fill teacher vacancies – such as recruiting from abroad.

Nick Oza for the Guardian

Inojosa is one of 12,000 foreign teachers who have come to the United States in the last five years on temporary J-1 cultural exchange visas . (The three-year visas offer no path to permanent residence in the United States.) Teachers on these visas represent just a small sliver of the 3.2 million teachers in American public schools.

But locally, these teachers can have a big impact.

Schools in almost every state have hired foreign teachers on cultural exchange visas. They include 13 Filipino teachers in Sacramento, 185 in Las Vegas and 26 in Casa Grande.

When Inojosa arrived in Arizona, a conservative state known for cutting funds for public schools, tensions brewed nationally over low teacher salaries.

Arizona ranked as one of the worst states for teachers’ pay in the US. Teachers there hit breaking point in April . Conservative state leaders, they said, were proposing a budget that failed, once again, to adequately fund schools. In coordinated demonstrations and walkouts tied to the national movement, teachers demanded more money for themselves and other staff in Arizona schools.

Their activism secured pay raises in schools throughout Arizona. Casa Grande teacher salaries, which had been well below the national standard, increased even more than most – an average of 18%.

For years before that, Casa Grande’s two public high schools, Vista Grande and Casa Grande Union, struggled with teacher turnover and teacher shortages – especially in math, science and special education. Teachers didn’t get a raise for five years and some saw their salaries drop.

Like many American towns , Casa Grande is not rich. It is ethnically diverse and largely conservative – it sits in a rural county where Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton by 19 points . Median household income in 2016 was $46,000, 20% below the national average .

The town of about 55,000 squats halfway between Arizona’s two largest cities, Phoenix and Tucson, amid scarred desert flatlands. Decades ago, desert saguaros were bladed en masse to make way for cotton farms and other profitable agricultural enterprises. But fluctuations in markets, along with water shortages, drought and climate change eventually changed the town’s fortunes, and it struggles to right its economy.

In the summer, the heat can be so intense the smell of hot pavement permeates the air. When it cools down, about 20,000 visitors spend the winter in Casa Grande. Some attend the local cowboy church, where the preacher wears cowboy boots and a white hat and stands before a pulpit fashioned out of a roping saddle.

When John Morris and his family settled in Casa Grande 14 years ago, the former big-city Californians enjoyed the small-town atmosphere. Morris, an automotive engineer, was immediately hired at Casa Grande Union high school. His low teacher salary led to financial pressures. Several years ago, he lost his home.

But Morris wouldn’t quit teaching. He felt his students needed him.

He now leads the school’s Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Academy. With his new raise, Morris will earn about $60,000, still $2,000 below the average salary for an American high school teacher.

Filipino teachers, who earn the same as American teachers in their pay grades, also got pay raises. Physics teacher Melvin Inojosa will earn about $53,000.

When the high school district first hired Filipino teachers in 2014, Morris and his wife, who was born in the Philippines, had a party for them.

has over a dozen Filipino teachers.

Nick Oza for the Guardian

The first Filipino teachers were interviewed via Skype. They were highly credentialed and taught in English – a legacy of the Philippines’ brief tenure as an American territory .

Math teacher Mark Cariquez, 28, arrived in Casa Grande from the Philippines two years ago. He found the locals “jolly” and felt welcomed and supported by the American teachers at the school. But he was stunned by the intense heat and news of mass shootings in America.

Cariquez earned about $300 to $400 monthly teaching in the Philippines. He makes about ten times more in Casa Grande. He quickly paid off the $12,500 up front costs to various agencies that helped him get the job and travel documents.

He lives frugally by renting a room in a house in Arizona City, a small town about 16 miles west of Casa Grande. He and his housemates, Noel Que and Marissa Yap, teach at the high school.

Cariquez shares a room with Que. Yap and her husband live down the hall.

Yap, 44, teaches biology while her husband works at Walmart, along with several other spouses of Filipino teachers and nurses.

Que, 50, has two kids and a wife. He can’t afford to bring them to the United States. He stays connected via Skype and sends money home every two weeks.

He often ships his family gift boxes stuffed with clothes, shoes, books and refrigerator magnets.

By living together, each teacher pays about $400 a month for rent, food, utilities and gasoline. This gives them spare cash to send home to their families and sightsee.

When teachers in Arizona demonstrated to protest their low pay, Cariquez, Que and Yap briefly joined school rallies to show solidarity. The Filipino housemates are happy with their salaries, but see a need for more educational funding.

Some Casa Grande locals who voted for Donald Trump do not support higher pay for teachers. Harold Vangilder, a 76-year-old retired army communications analyst, finds it “offensive” when teachers gripe about their salaries, given the poverty in the town. Vangilder, a conservative, is a build-the-wall guy. Still, he applauds hiring foreigners to resolve teacher shortages. After all, they have their papers.

“They’re helping to ‘make America great’ by educating our kids,” he said.

Dominick DePadre wants public education privatized. DePadre earned a graduate degree in education, and once taught at Casa Grande Union. He quit in 2006, after turning down a contract that would have paid him $39,000 a year. Now 44, DePadre owns a local landscaping company.

Teachers, he said, should get out of teaching if they don’t like their pay, and not ask “for handouts”. Still, he doesn’t necessarily agree with hiring foreign teachers to take vacant American jobs. But, he said, “it sounds like an act of desperation”.

Inojosa, the physics teacher at Vista Grande, understands desperation. His childhood home in Manila was made of wood scraps, and he’s known hunger. In Casa Grande, he recognizes hunger in some of his students and always keeps extra cookies in his book bag.

He tries to serve as a role model, and tells his students about hardships in the Philippines.

Inojosa and his wife, Bennielyn, just moved into a small apartment in town. Except for a bed, a triptych of a tree they bought for $3 at a thrift store, and a small table for grading papers, they have no furniture. They’ll get what they need when they can, and they’re happy to no longer be living with teacher roommates.

Bennielyn, a certified accountant in the Philippines, is a special education aide at her husband’s school.

Recently, as the couple stopped at a red light on their drive to school, a stranger with something in his hand knocked on their window. Inojosa feared the American man held a gun. But it wasn’t a gun.

It was Inojosa’s iPhone 8. He’d accidentally left it on top of his car.

He was touched by the stranger’s kindness.

“Welcome to America,” Bennielyn said.

Casa Grande feels like home.

Inojosa, who chairs the science department at his school, is well respected by students, colleagues and the administration. They tell him they wish he could stay. He wishes he could, too. But his three-year visa expires in the summer of 2019. He has an option to renew for two years and then must return to the Philippines – unless he can obtain a more competitive visa that offers a path to a green card.

The couple’s future remains uncertain, particularly under the Trump administration’s unpredictable immigration policy shifts.

So is the future of Filipino teacher recruitment at Casa Grande schools. The recent raises made it easier for administrators to retain and hire teachers. For the first time in four years, the district did not look to the Philippines for new teachers.

Inojosa will teach in Arizona as long as he can. If authorities want him to leave, he’ll leave. No hard feelings. He respects American laws. He’ll find a job teaching someplace else in the world, and “make my own happiness”.

Because teaching, he said, “is what I am”.

Picking lettuce and teaching our children...

The jobs that are unworthy of our support.