Manafort Tried to Broker Deal With Ecuador to Hand Assange Over to U.S.

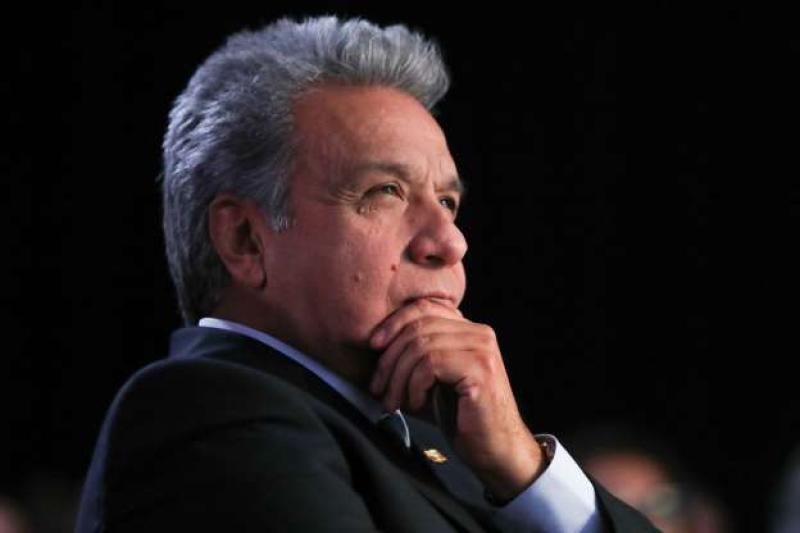

WASHINGTON — In mid-May 2017, Paul Manafort, facing intensifying pressure to settle debts and pay mounting legal bills, flew to Ecuador to offer his services to a potentially lucrative new client — the country’s incoming president, Lenín Moreno.

Mr. Manafort made the trip mainly to see if he could broker a deal under which China would invest in Ecuador’s power system, possibly yielding a fat commission for Mr. Manafort.

But the talks turned to a diplomatic sticking point between the United States and Ecuador: the fate of the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange.

In at least two meetings with Mr. Manafort, Mr. Moreno and his aides discussed their desire to rid themselves of Mr. Assange, who has been holed up in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London since 2012, in exchange for concessions like debt relief from the United States, according to three people familiar with the talks, the details of which have not been previously reported.

They said Mr. Manafort suggested he could help negotiate a deal for the handover of Mr. Assange to the United States, which has long investigated Mr. Assange for the disclosure of secret documents and which later filed charges against him that have not yet been made public.

Within a couple of days of Mr. Manafort’s final meeting in Quito, Robert S. Mueller III was appointed as the special counsel to investigate Russian interference in the 2016 election and related matters, and it quickly became clear that Mr. Manafort was a primary target. His talks with Ecuador ended without any deals.

There is no evidence that Mr. Manafort was working with — or even briefing — President Trump or other administration officials on his discussions with the Ecuadoreans about Mr. Assange. Nor is there any evidence that his brief involvement in the talks was motivated by concerns about the role that Mr. Assange and WikiLeaks played in facilitating the Russian effort to help Mr. Trump in the 2016 presidential election, or the investigation into possible coordination between Mr. Assange and Mr. Trump’s associates, which has become a focus for Mr. Mueller.

Mr. Manafort and WikiLeaks have both denied a recent report in The Guardian that Mr. Manafort visited Mr. Assange at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London in 2013, 2015 and 2016.

But the revelations about Mr. Manafort’s discussions in 2017 about Mr. Assange in Quito underscore how his self-styled role as an international influence broker intersected with the questions surrounding the Trump campaign.

And the episode shows how after Mr. Trump’s election, Mr. Manafort sought to cash in on his brief tenure as Mr. Trump’s campaign chairman even as investigators were closing in.

The Ecuadoreans continued to explore the possibility of Chinese investment, but with the United States Justice Department and intelligence agencies stepping up their pursuit of Mr. Assange and WikiLeaks, Mr. Moreno’s team increasingly looked to resolve their Assange problem by turning to Russia.

In the months after Mr. Moreno took office, the Ecuadorean government granted citizenship to Mr. Assange and secretly pursued a plan to provide him a diplomatic post in Russia as a way to free him from confinement in the embassy in London. (That plan was ultimately dropped in the face of opposition from British authorities, who have said they will arrest Mr. Assange if he leaves the embassy.)

Jason Maloni, a spokesman for Mr. Manafort, said that it was Mr. Moreno — not Mr. Manafort — who broached the issue of Mr. Assange and “his desire to remove Julian Assange from Ecuador’s embassy.” Mr. Manafort “listened but made no promises as this was ancillary to the purpose of the meeting,” said Mr. Maloni, adding, “There was no mention of Russia at the meeting.”

Late last year, Mr. Mueller’s team charged Mr. Manafort with a host of lobbying, money laundering and tax violations in connection with his consulting work for Russia-aligned interests in Ukraine before the 2016 election. Mr. Manafort was convicted of some of the crimes and pleaded guilty to others as part of an agreement to cooperate with prosecutors. But prosecutors said last week that he violated the deal by repeatedly lying to them. Mr. Manafort remains in solitary confinement in a federal detention center in Alexandria, Va., waiting for a judge to set a sentencing date.

The trip to Ecuador was part of a whirlwind world tour that represented the last gasps of Mr. Manafort’s once lucrative career.

In those final months, Mr. Manafort pitched officials from a range of governments facing a variety of challenges, from Puerto Rico to Ecuador to Iraqi Kurdistan to the United Arab Emirates. Mr. Manafort, who served on the board of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation in the Reagan administration, presented himself as a liaison to the new Trump administration and, in some cases, as a broker for arranging investments from a fund associated with the state-owned China Development Bank.

In Quito, he told Mr. Moreno’s team that he could arrange a major cash infusion from the Chinese fund in the Ecuadorean electric utility, and could ease any potential concerns from the Trump administration about such an investment, according to people involved in arranging the meetings.

The week after the Quito trip, Mr. Manafort traveled to Hong Kong to meet with representatives from the China Development Bank’s fund to discuss the possible investment in Ecuador, as well as a proposal being pushed by Mr. Manafort to buy Puerto Rico’s bond debt, possibly in exchange for ownership of the island’s electric utility.

In both cases, Mr. Manafort assured the Chinese he could win support from Washington, despite Mr. Trump’s oft-expressed qualms about China.

Brokering a deal to bring Mr. Assange to the United States could have been even more complicated. Not only had Mr. Assange not been charged at the time of Mr. Manafort’s trip, but Mr. Assange’s work was — and remains — a particularly fraught matter for Mr. Trump and his team.

Mr. Trump and his allies had cheered on WikiLeaks during the campaign, when it released troves of embarrassing internal emails and documents stolen from the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman. Since then, though, the United States intelligence agencies and Mr. Mueller’s team have made the case that the documents were stolen by Russian government agents, 12 of whom were charged by Mr. Mueller.

Mr. Assange had been pursued by Swedish prosecutors on a rape accusation from 2010. The Ecuadorean Embassy in London granted him asylum in the summer of 2012. That was under Mr. Moreno’s predecessor, Rafael Correa, whose political identity was based partly on his antagonism toward the United States. Swedish authorities abandoned their attempt to extradite him last year, which invalidated the warrant for his arrest.

During Mr. Correa’s last day in office, the Ecuadorean government wrote a letter repeating its requests to Britain to accept Mr. Assange’s asylum status. The letter asserts that United States officials had left “no doubt about their intention to persecute Mr. Assange with the aim of punishing him for alleged offenses.”

Mr. Moreno had signaled during his campaign that he would like to wash his hands of Mr. Assange. And last December, Ecuador began carrying out the plan to move Mr. Assange to Russia as a diplomat, which would require him to become an Ecuadorean citizen.

In a citizenship interview at the embassy in London, Mr. Assange explained that he wanted to become a citizen because “I’ve been welcomed here for the last five years and I feel practically Ecuadorean,” according to a written summary of the meeting.

Within 10 days, Mr. Assange was granted citizenship, according to documents released by Paola Vintimilla, an Ecuadorean lawmaker who opposes Mr. Assange’s presence in the embassy. But a subsequent effort to grant Mr. Assange diplomatic status, and the immunity that would come with it, was rejected by the British government.

Correction: December 3, 2018

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Swedish prosecutors had pursued Julian Assange on a rape charge. Although he was investigated over a rape accusation, he was never charged.

I don't understand-the narrative is that President Trump somehow consorted with the Russians, but the data went through Assange, who if he was here, supposedly would bring the whole house tumbling down. So, why would they want him here? Unless, of course, the narrative is wrong......

So, no ideas on how this makes sense? Seems like if this is true, that the narrative that peole have been pushing is not......

Nothing makes much sense in the political climate nowadays. Making deals for China sounds really odd.

I do believe Ecuador wants him out of their embassy. I think they are getting fed up with him.