This federal agency is quietly, profoundly shaping climate policy

FERC sits at the heart of the clean energy transition, overseeing two key areas of frequent conflict. The first is bulk electricity — interstate transmission lines and regional wholesale power markets. The second is natural gas infrastructure; the agency licenses the siting and building of all new pipelines.

FERC licenses every new natural gas pipeline.

Shutterstock

FERC is composed of five commissioners; by law, no more than three may be from one party. In a series of 3-2 decisions, the Trump-appointed Republican commissioners have effectively refused to take climate into account at all in pipeline decisions. This has prompted a series of scathing dissents from Commissioner Richard Glick, a former Democratic Senate aide whom President Trump appointed to the commission in 2017.

From left: FERC Commissioners

Kevin McIntyre, Cheryl LaFleur,

Neil Chatterjee, Robert Powelson,

and Richard Glick, in June 2018,

before Powelson left .

@RichGlickFERC/Twitter

Their conclusion, in a nutshell, is that FERC doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel to address climate change. It doesn’t need a new regulatory regime or new authorities. It just needs to diligently obey its current mandates.

In electricity, it has no mandate to address climate directly, but it does have a mandate to maintain open, competitive markets — and these days, doing so has “the effect, if not the intent, of facilitating a cleaner, less GHG-intensive energy mix.”

When it comes to pipelines, they argue, FERC does have a clear mandate to take climate effects into account. Such decisions are supposed to be guided by the “public interest,” and, as they say, “it is hard to imagine a consideration more relevant to the ‘public interest’ than the existential threat posed by climate change.” This conclusion has been confirmed by several recent federal court decisions instructing federal agencies, indeed FERC itself, to take climate into account.

The paper is a call for FERC to recommit to its existing obligations. Those obligations are, in some cases, fairly technical, but they have substantial greenhouse gas implications. So I called Commissioner Glick (Christiansen also sat in) to walk through some of his arguments. Among other things, we talked about FERC’s mandates, the growth of distributed energy resources, the possibility of expanding wholesale electricity markets, his disagreement with his Republican chair over pipelines, and whether Trump will succeed in politicizing the agency.

It was a long, wonky, and, if you’re interested in any of the issues under FERC’s purview, fascinating conversation. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

FERC’s authority over electricity, and how it affects climate change

David Roberts

Do you think that FERC has been doing a good job so far dealing with climate change?

Richard Glick

We have a responsibility under NEPA [the National Environmental Policy Act] to examine whether environmental impacts associated with an infrastructure project are significant. And to me, one of the most significant environmental impacts out there is climate change.

With regard to pipelines, we’ve been doing a poor job. Not only are we not doing what’s required by statute, we’re not doing what the DC Circuit told us to do in the Sabal Trail case .

Even after being admonished by the DC Circuit, the commission has consistently been avoiding its responsibility to consider whether the climate change impacts of a natural gas facility — especially pipelines, the downstream impacts and even the direct impacts — are significant, whether the greenhouse gas emissions have a significant impact on the environment. We’re just ignoring that. We’re refusing to make that finding, one way or the other.

With regard to electricity, I think we’re doing a better job of that. The commission over the last decade or so has been slowly trying to focus on getting rid of barriers to newer technologies — things like storage, wind, and solar.

Matthew Christiansen

The article doesn’t confront the question of whether FERC could, in its authority on the electricity side, address climate directly. The argument the article makes is that even under a conventional understanding of FERC’s responsibility, there are a number of things it can do that can have very large impacts for climate.

David Roberts

Getting all up in yer wholesale markets.

Shutterstock

Richard Glick

The courts have been relatively clear that our jurisdiction is limited to matters directly affecting wholesale rates. It hasn’t been litigated yet, but I’d be reluctant to suggest that we have the authority to more directly regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

But I would say that’s not necessarily that significant. The fact is that consumers are demanding access to zero or lower emissions generation. And not just residential consumers; it’s also commercial and industrial consumers. That’s where demand is coming from these days.

Our role is to adapt, to make sure there’s no undue discrimination, to make sure that rates and terms of service adjustments are reasonable.

But we can’t directly regulate or limit greenhouse gas emissions through our Federal Power Act authority.

The uneasy relationship between FERC authority and state authority

David Roberts

One of the sources of conflict and controversy facing FERC these days, on the electricity side, has to do with the relationship between FERC authority and state authority. So let’s start with the basics. The Federal Power Act sets up a relationship between FERC and the states known as “cooperative federalism.” What does that mean?

Richard Glick

Congress gave FERC authority over wholesale electric markets and interstate transmission of electricity. But they explicitly said that states have authority over resource decision-making.

David Roberts

As you say, the lines between federal and state authority have been getting blurrier. States are passing energy policies that, for various reasons, advantage cleaner sources. Some [wholesale market managers] are saying, “FERC’s job is to create a level playing field. It says so right there in the charter. These state policies have skewed the playing field and FERC needs to rebalance it.” How do you resolve that tension?

Richard Glick

I would argue states have been skewing the playing field since the advent of government regulation of electricity.

The zero-emissions credit, the nuclear credit program, the renewable energy credit program, RPS programs — there are hundreds of these state programs. Some of them, in fact, encourage gas generation or coal generation. For instance, all the work the government has done on fracking has arguably had a dramatic impact on the price of natural gas.

If [FERC] tried to balance all that out, to create that level playing field — which is somewhat of a myth, because there’s never going to be a complete level playing field — we’re back to where we started. We just have to recognize that we don’t have real, truly competitive markets out there; we have managed competition.

States have to recognize that we have authority over wholesale rates; for instance, the Supreme Court said a state can’t take action that directly interferes with or sets wholesale rates. But at the same time, we can’t then tell a state, “You can’t do your zero-emissions credit program, even though you think greenhouse gas emissions are an issue you should address at the state level.”

David Roberts

Right. So it’s less like creating a level playing field and more like preserving the playing field that you inherit from states. [Laughter]

Matthew Christiansen

It goes to your question about cooperative federalism. There are some things the commission does and some things the states do. In order for those two sovereigns to cooperate, the commission has to respect what the states are doing.

But at the same time, the commission’s core responsibility is to break down the barriers that exist within its jurisdiction — a market rule, for example, that prevents a battery from providing a service that a gas generator is allowed to provide, without any real rationale. That’s the kind of thing we have in mind.

How FERC can (and should) deal with distributed energy resources

David Roberts

David Roberts

Distributed energy resources (DERs), basically.

Shutterstock

More and more distributed energy resources (DERs) are aggregating together and bidding into wholesale markets. [See this article for much more on that.] It seems to me that as DERs get more prevalent and more complicated, this line between state jurisdiction and federal jurisdiction is only going to get blurrier. Do you think the market construct we currently have — with DERs both serving reliability at the retail level and bidding into markets at the wholesale level — is going to hold up over the long term?

Richard Glick

First off, that’s an excellent question. When Norman Bay was chair, just before he left, FERC proposed a combined rulemaking that would have required RTOs and ISOs to come up with rules to facilitate participation in their wholesale markets by both energy storage and by aggregated distributed energy resources. [After Bay left,] the commission split those proposals into two. We went forward with the storage rule, but the distributed energy resource rule is still pending. I am very interested in finalizing that rule so we can get the RTOs to come up with rules facilitating DER integration.

But to come back to your point, the lines that were drawn [between state and FERC jurisdiction] in 1935 when Congress enacted the Federal Power Act, and even subsequently, over time, like in 1992 when it made significant changes to the Federal Power Act, the times were a lot simpler. It was a lot easier to tell what a wholesale transaction was and a retail transaction was, and where distribution facilities stopped and transmission facilities began.

That’s not the case today. You have distributed energy resources behind the meter, and they’re capable of providing significant benefits to wholesale markets. And we have authority over wholesale transactions, but the states have a legitimate interest in ensuring that their distribution systems are operated reliably.

I think there are ways to accommodate both. People have suggested that maybe the Federal Power Act needs to be updated to address some of these concerns, to redraw the line. That’s not necessarily a bad idea. I think it would be helpful for us. But that could take a long time, so FERC has to operate within the authorities we have today.

How FERC can best serve grid resilience and long-distance transmission

David Roberts

Recently, there have been a lot of debates about the resilience of the energy grid, its ability to stay functional during times of weather stress or attack. The Trump administration tried to bail out coal plants on the basis that they are “fuel secure,” i.e., have giant piles of fuel on site, which is allegedly necessary for grid resilience. How do you see FERC’s role in the resilience conversation?

Richard Glick

Several months after President Trump came into office, the Department of Energy proposed a rulemaking to FERC that would have required us to compensate generation facilities that have 90 days of fuel or more on hand. Somehow that was going to help the resiliency of the grid.

What’s notable is that all five commissioners agreed there just wasn’t anything in the record the Department of Energy provided to FERC to suggest there was a resilience problem that could be addressed through subsidizing coal and nuclear generation.

When we dismissed the DOE proposal, we created a new docket, asking several questions: 1) How do you define resilience? 2) Do we have a resilience problem? And 3), if we do have a problem, how should we fix it?

We’ve received an enormous number of comments. So far, from what I’ve seen of those comments, there really isn’t a problem, at least in terms of grid resilience. There is no suggestion that more coal generation or more nuclear generation would make our grid any more secure.

To the extent we have problems, it’s mostly on the transmission and distribution side. One example would be, as the impact of climate change continues to grow in your part of the country, wildfires have an impact on the transmission grid. So those are the kinds of things I’d like to see us address, not subsidizing generation with 90 days of supply.

Cold weather has an impact on all technology; there just isn’t anything to suggest that we’ll be free and easy if we figure out a way to keep coal plants and nuclear plans operating.

David Roberts

The long-distance transmission grid is a huge piece of the clean energy puzzle. FERC has a docket open reexamining its transmission authority. What would you like to see come out of that? Dynamic line ratings? An offshore wind spine? What would you like to see FERC do around transmission?

Richard Glick

We have a proceeding ongoing, examining our approach to granting incentives for transmission. Back in 2005, Congress gave FERC the authority to provide incentives for transmission and over time, FERC was first criticized for giving too many incentives, and then it revised its policy and was criticized for not giving enough incentives.

There are a few things I’d like to see come out of this proceeding.

First of all, I’d like to review our existing incentives to see whether they make sense now. There are some I don’t believe actually encourage the development of transmission.

And there are other incentives we might want to put on the books to help utilities and other investors. You mentioned dynamic line ratings — I don’t think there’s enough incentive for utilities now to invest in making the existing grid more efficient. In most cases, they get a greater return when they invest significant capital in something. They’re not encouraged to invest in little things like facilitating dynamic line ratings, which might greatly improve the efficiency of existing transmission assets. That’s one thing I’d like to see us take a look at.

The other thing is whether we need to provide greater incentives to access remotely located resources, especially in terms of rightsizing transmission. If an area is very windy and you can build up to 10 200-megawatt wind farms, and we build a transmission line that’s just going to satisfy the first 200-megawatt wind farm, is that the right thing to do? Or should we figure out a way to incentivize rightsizing transmission?

All of my colleagues agree that more needs to be done on transmission, especially to access remotely located renewables. We have to figure out whether our current incentives are the right approach or if we need to take a new approach.

Thumbs down to capacity markets and up to the possibility of a Western regional energy market

David Roberts

A recent paper co-authored by FERC’s chief economist argued that mandatory capacity markets, by their structure, tend to favor natural gas. [Capacity markets pay power generators to be available, in reserve, as opposed to energy markets, which pay for electricity produced.] Do you think capacity markets are working?

Richard Glick

There are rules I can’t talk about because they’re still pending in front of the commission, but I have serious reservations about mandatory capacity markets, in large part because I don’t think they work the way they’re intended to. Capacity markets are supposed to be not only encouraging new generation to come in but also encouraging inefficient generation to retire. That’s not happening very well. Some mandatory capacity markets are producing significantly greater amounts of capacity than needed to meet the reserve margin target.

What’s interesting to me is that, now that we have low natural gas prices and much more zero-marginal-cost wind and solar on the grid, it’s leading to reduced prices. So people are arguing that mandatory capacity markets need to be changed — a proposal not really aimed at making the market more efficient, but aimed at increasing the price. [laughter] They feel they’re not being compensated sufficiently and want to increase the rate they get from capacity markets. I don’t think that was the intent of the economist who came up with this concept.

Resource adequacy is an important issue. I just have strong reservations about whether mandatory capacity markets are the best way to achieve resource adequacy.

David Roberts

What thoughts, if any, do you have on the prospect of a regional Western [wholesale energy market] ?

Richard Glick

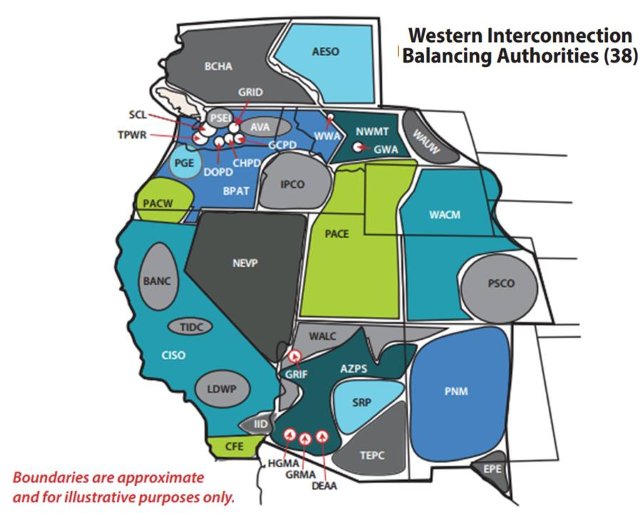

I’m a big believer in regional coordination and regional efforts because, as we’ve seen in other parts of the country, they help to integrate variable generation, wind and solar, much more efficiently and much more economically. And they also provide greater reliability. If you didn’t have 38 balancing authorities [in the West], you would have much less need for certain types of investments in generation. So I think regional coordination is much more efficient, and beneficial for consumers.

All these areas currently do their own electricity resource planning. WECC

Having said that, I also recognize the long history of these efforts in the West, and the concerns that have been raised about governance, whether California might have too much influence over the other states.

So from FERC’s perspective, the best thing we can do is encourage the parties to have discussions. The region has to come up with its own approach, organically, through discussions with member states and other stakeholders.

FERC’s obligation to grapple with the climate effects of natural gas pipelines

David Roberts

Moving on to pipelines: Your paper argues that FERC has a direct, first-order responsibility to consider the environmental impacts of infrastructure projects, including the climate impacts. But your colleague [FERC Chair] Neil Chatterjee has argued that FERC does not have the authority or ability to consider climate impacts in permitting decisions. [In a 3-2 ruling, FERC recently adopted a policy sharply restricting consideration of climate impacts .] What’s your argument for why FERC ought to consider those impacts?

Richard Glick

First of all, what the chairman said is wrong: There’s nothing in the Natural Gas Act that prohibits [considering climate impacts]. As a matter of fact, the DC Circuit Court, in the Sabal Trail case , told us exactly the opposite, that we have a responsibility to examine greenhouse gas emissions to the extent that they’re reasonably foreseeable.

Not only do we have a responsibility under NEPA, but also, under the Natural Gas Act, after we have performed NEPA analysis, we’re supposed to determine whether the proposed project is in the public interest.

So we weigh the benefits of the project — say you’re bringing gas into an area that needs more — against the adverse environmental impacts. There are other factors to balance, too, but for the most part, you balance those two factors.

The DC Circuit told us we have to do it. So I strongly disagree with Chairman Chatterjee. But to the extent he has legitimate misgivings about our authority, I’ve offered to work with him on a legislative proposal to Congress. We could get something up to Congress relatively quickly and ask them to pass it.

But to me it’s very clear, based on the court decision in Sabal Trail, that we have that authority already.

David Roberts

You believe FERC has the statutory authority to consider both upstream and downstream effects? [Upstream effects happen prior to the pipeline, from natural gas production. Downstream impacts happen after the pipeline, for instance when the natural gas is burned in a power plant.]

Richard Glick

The NEPA standard is reasonable foreseeability. To the extent it’s reasonably foreseeable that the addition of a pipeline will lead to more burning of natural gas downstream, or more production upstream, then I think we do.

In some cases, it may not be reasonably foreseeable, we can’t figure it out, in which case, we don’t have authority. But to the extent we can figure it out, we should — not only should, we have to.

David Roberts

Why not, when making these determinations, just use the social cost of carbon [the federal government’s official estimate of the total cost of the impacts of a single ton of carbon emissions]?

Matthew Christiansen

Commissioner Glick has dissented several times on the basis of the commission’s refusal to consider the social cost of carbon. With a problem as nebulous as climate change, it’s hard to put it into concrete terms. Having a tool that puts it in discrete monetary terms that everyone can understand seems like the perfect way to contextualize the harm caused by CO2 emissions. We’ve been adamant about that; it’s just no other offices are agreeing right now.

Look at the environmental impact statements associated with these projects that we have to prepare as part of the NEPA process. We consider a whole bunch of environmental impacts, and they’re not all easy to measure, but we don’t say, “Oh, this is too hard, we’re not going to consider it.” We consider those impacts, and in many cases, we mitigate those impacts. But the majority of the commission has chosen to stick a pin in this matter and not consider this particular environmental impact.

David Roberts

David Roberts

Say the majority of commissioners simply refuse to consider climate impacts in pipeline decisions. Is there any remedy? Could it go to the Supreme Court? Or are you just stuck?

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Richard Glick

The court has already told them once to do it. The Sabal Trail case was very clear. It’s just that the commission, in my opinion, intentionally misconstrued what the court told us to do.

So I think the court has to continue to tell them to do it. Some of these orders that get litigated, it takes a long time for them to get through the appellate process. Nonetheless, eventually some of these cases are going to get to the Circuit and maybe the Supreme Court. The courts will tell us what we have to do.

Maintaining FERC’s independence in the face of Trump’s pressure

David Roberts

When FERC rejected Trump’s first attempt at a coal bailout , political observers celebrated the agency’s independence. Currently, you only have four commissioners. LaFleur [the other Democrat] has announced that she’s leaving . Trump will have two more appointments at least. Do you think he is trying to politicize FERC the way other federal agencies have been politicized? And if so, do you think he’s going to succeed, or do you think FERC’s independence is resilient against that kind of pressure?

Richard Glick

And that’s no pun intended with “resilience”?

David Roberts

Right. Is FERC fuel-secure? [laughter]

Richard Glick

First of all, that’s a totally legitimate question, because FERC has such a great reputation for being an independent agency, through many Democratic and Republican administrations. People are always concerned about that.

But I would just point again to the 5-0 decision on resilience. If the three Republican commissioners were puppets of the administration, they would have voted yes, but they did not. They all voted no.

David Roberts

I just worry that Trump saw that and thought, “Oh, I need better puppets.”

Okay, as a final matter, several people on Twitter have demanded that I ask: Is there any possibility of updating eLibrary [FERC’s database of dockets and legal filings] so that it performs with 21st-century speed and reliability?

Richard Glick

There are certain disadvantages to not being the chairman. One of the few advantages is I don’t have authority over those kinds of issues.

Tags

Who is online

55 visitors

For wonks.

Long but interesting, thanks.

It's kinda "fly on the wall". That's unusual.