Norman Rockwell, Realist

F or the past few months, the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass., has been traveling the Four Freedoms paintings by Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), which the museum owns. Rockwell finished them in 1943. They were quickly published in The Saturday Evening Post and became famous. The show, Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt, and the Four Freedoms , opens this week at the Museum of Fine Arts in Caen in Normandy as part of the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion on June 6. Also 75 years ago, in wartime America, these paintings travelled to department stores throughout the country as the calling card for the federal government’s most lucrative war-bond drive ever. It raised $133 million, equal to about $2 billion today.

I’ll write this week and next about these four pictures. They’re the visual mission statement for America’s role in World War II. They’re also part of the visual vocabulary for most Americans thinking about what it means to be an American.

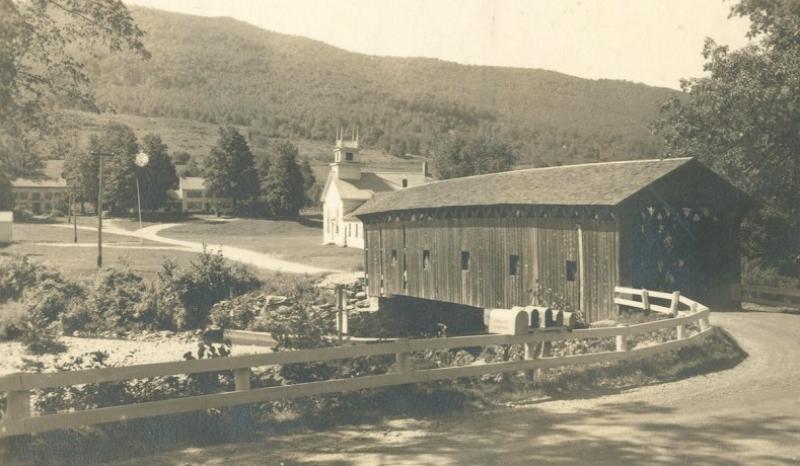

My perspective is possibly unique, since as far as I know, I’m the only art historian in tiny Arlington in southwestern Vermont, where Rockwell lived when he made these images. I know for certain that I’m the only art historian from Arlington who both writes for National Review and knew many of the models Rockwell used. These pictures, as I’ll show, are very much products of the real Vermont as Rockwell experienced it when he lived here between 1937 and 1953.

Rockwell visualized four subjects — freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear — inspired by a 1941 speech President Franklin Roosevelt delivered before a joint session of Congress. Less than a year before the Pearl Harbor attack and as the European war raged, Roosevelt pitched what soon became the heart of America’s wartime mission statement.

First, who saw these pictures? The better question is “who didn’t?” or, today, “who hasn’t?” They’re icons, and it’s worth asking, “icons of what?” The four paintings were done exclusively for publication in The Post , which commissioned the project by Rockwell, who worked as the magazine’s top illustrator. They appeared in the publication, America’s preeminent news and lifestyle periodical, over four weeks in 1943. The Post then had a circulation of about 3 million.Millions bought a special reprint of the series. The Office of War Information (OWI) distributed about 8 million posters advertising the government’s 1943 Series E war bonds. Since the end of the war, countless millions have seen the images, with Freedom of Speech for many years the symbol for the American Civil Liberties Union, before it abandoned its mission of championing unfettered free speech for defending only speech it likes.

Left : Freedom of Speech , 1943, by Norman Rockwell. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum). Right : Poster from story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post , 1943, Office of War Information. (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum)

What inspired the paintings at that moment? Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms started as fears, or a single “fear of fear itself,” articulated first in his 1933 inaugural speech. Preparing for his 1941 State of the Union speech, Roosevelt first thought he’d develop the theme of fear further by evoking fear of losing free expression and free worship. He added fear of war and fear of a war-torn, collapsed economy.

It was, he thought, an awkward leap. He landed on the theme of freedom, not fear, as the driver of a new international order. He thought it was more positive and aspirational. Five freedoms — freedom to access information, freedom of expression, worship, and the press, and freedom from want — were whittled to four and then refined. When he addressed Congress on January 6, 1941, the four freedoms were freedom of speech and of worship and freedom from want and from fear.

The speech, centered around the new Lend Lease program, was a dud. If it inspired anything, it was anxiety. Was freedom from want and from fear code for socialism? Many thought these two freedoms invited more government intervention and guarantees, and by 1941 big chunks of the public saw the New Deal itself as a dud. Roosevelt kept pushing the Four Freedoms marketing theme without much traction, even after the Pearl Harbor attack. His Office of War Information was often inept. The number of freedoms grew larger and more trivial, including at one point freedom to borrow money at low interest rates. It wasn’t until Rockwell visualized them that the Four Freedoms finally took off. After Rockwell’s conception appeared in The Post , OWI quickly appropriated them and used them with abandon.

Three of these pictures — Freedom of Speech , Freedom of Religion , and Freedom from Want — are among the best-known works of American art. Whistler’s portrait of his mother, Grant Wood’s American Gothic , and Washington Crossing the Delaware , by Emanuel Leutze, are their only competition. When I was in graduate school, intellectuals, especially art historians, viewed Rockwell with contempt. He was an illustrator, so for those believing an impregnable wall separated high art — painting, prints, drawing, and sculpture — from low art, or commercial art, Rockwell was a no-account. That he made a very good living from it was worse. Most academics look with scorn at artists who get rich.

On the one hand, critical opinion dismissed Rockwell as a fantasist, a myth maker, a nostalgia peddler. On the other, Rockwell and his masters at The Post are faulted for presenting as a great, coveted good a world that the artist might have faithfully portrayed but that was too Christian, rural, patriotic, Republican, and what many would call today “heteronormative.” Rockwell’s style was representational. “Bad,” I heard. “That’s for simpletons.” His subjects lacked angst. “What’s life without angst?” Rockwell seemed doomed to cornball obscurity. Sometimes you find people who’ll never be satisfied.

It’s quite a trick to be wrong about so much. Yes, Rockwell was out of fashion even in middlebrow America by the 1970s. His bread and butter — magazine and calendar illustration — was a disappearing art long before he died in 1978, displaced by color photography. His anchor employer, The Saturday Evening Post , folded in 1971. He worked for the Boy Scouts of America until 1976, producing illustrations for his last of 64 years’ worth of annual calendars. In academia, it was not until the American Studies movement blossomed in the 1980s that Rockwell’s work was critically resuscitated. Unpacking Rockwell’s work was a gold mine of American civic myth. But how much of it was myth?

The fact is, Rockwell is a realist in the tradition of the great 19th-century American realists like George Caleb Bingham, Francis Edmonds, William Sidney Mount, and Eastman Johnson. The real fantasists are the academics and highbrow critics who claim that Rockwell’s world didn’t exist. Rockwell depicted the everyday life of what was then called “the common man,” whom Rockwell found in Arlington, Vt.

I combed through the 1940 census to get a demographic sense of Arlington, which no one else has done. I found that the Four Freedoms pictures convey the place with perception and correctness. This is nothing for which the artist — or the art — needs to repent. He was working in Vermont, using Vermont models, and expressing strands of Vermont culture. For Rockwell’s critics, he presents some favorite hate charms. His subjects are rural. They’re working-class. They’re not sodden with weepy grievance.

Overwhelmingly, Arlington was working-class, white, and native-born. Of its 1,418 people, 29 percent lived on a farm. Arlington had one densely populated neighborhood — East Arlington — but was otherwise rural. East Arlington contained a one-road business district of grocery stores, a barber shop, a hardware store, and Hale Furniture Company, a manufacturer of home and office furniture with about 300 non-union employees, and considerable low-density factory housing. There were no African Americans or Asian Americans in Arlington. About 8 percent were foreign-born.

Arlington is in the geographic center of Bennington County. In 1940, half of Bennington County’s rural, non-farm population had some high school education. Only 15 percent were high school graduates. About 5 percent were college graduates. Of non-farm working men, 11 percent were professionals, business owners, or managers. Thirty percent were laborers and factory workers. About 11 percent of working-age men were unemployed in 1940, though this had surely changed by 1943 given a new state of full, wartime employment. The balance were craftsmen, foremen, service workers, clerks, and sales people. Of non-farm females over 21, about a third were employed.

Arlington is about 60 miles from Albany, N.Y. It’s not exactly in the middle of nowhere. In 1932, avant-garde Bennington College opened about ten miles south. Rockwell audited classes there. Historically, Arlington shares something with Carthage, Xian, and Constantinople. It was once a national capital. Vermont was not one of the 13 original states. It’s the 14th state. In 1777, Arlington was the first capital of the Vermont Republic, the wild frontier between New Hampshire and the Hudson River. Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, the riffraff band of profiteers and guerillas, lived in Arlington, next-door Sunderland, and Bennington. That was Arlington’s time in the spotlight. It faded into rural, workaday insignificance. Its population in 1940 was about the same as in 1800.

Arlington is about 200 miles north of New York City, a few hours’ drive, but light years away in almost every respect, today and in the 1940s. Rockwell was born and raised on the Upper West Side in Manhattan. He lived in Manhattan until he and his wife, Mary, moved to New Rochelle in the early 1930s. When he visited one summer in the mid-1930s, he quickly felt Vermont’s otherness and was direct in describing it. He liked it, too.

Rockwell came to Arlington to withdraw from the city life, and in his autobiography, he was direct in describing Vermont’s attraction. “The people we met were rugged and self-contained . . . none of that sham ‘I am soooo GLAD to know you’ accompanied by radiant smiles,” he said. “They shook my hand, said, ‘how do,’ and waited to see how I’d turn out.” Vermonters were “not hostile but reserved with a dignity and personal integrity which is rare in suburbia, where you’re familiar with someone before you know him.”

“It was like living in another world . . . a more honest one somehow,” Rockwell wrote. “Because almost everyone had lived in the town all his life and had known one another since childhood and even everybody’s parents and grandparents, there could be little pretension.” Rockwell understood that since so many people in town were farmers, there was less of a spirit of competition. “The pressures were very strong, not toward conformity, but toward decency and honesty. . . . A mean-tempered man would soon find soon felt isolated since his neighbors wouldn’t be bothered with him.”

Freedom of Worship , 1943, by Norman Rockwell. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum)

Rockwell drew his themes from everyday life in Arlington, using local people, not professional models. Carl Hess, the model for the central figure in the Freedom of Speech picture, owned a gas station near Rockwell’s house, one of two in town. He was owner, mechanic, and gas pumper. To his left is Bob Benedict, who owned and operated the other gas station. In Freedom of Worship Walt Squires, a carpenter in Arlington, modeled for the vaguely foreign figure, wearing what is likely a kufi. Jim Martin, one of Rockwell’s neighbors, modeled for the chin-stroking agnostic. Rose Hoyt, the young woman holding rosary beads in the picture, was a Rockwell favorite. Her husband was part of the Arlington road crew. He made 38 cents an hour. He and his wife had eight children. These and many of Rockwell’s models were his social set. Aside from Squires, no one disguised his appearance. Rockwell found in the average people in Arlington his Everyman and Everywoman. It’s the real world of 1940s Vermont: simple, reserved, honest, and straightforward.

Next week, I’ll look at each picture, examining what they meant then and now.

BRIAN T. ALLEN is an art historian.

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

A tribute to the great realist painter, who loved America and it's people.

Very good article, Vic. My dad was a big fan of Rockwell's artwork.

I paint, so I always appreciated Rockwell's work. The man was totally underrated and dismissed as an illustrator instead of a true artist, who captured American life. He captured all the important moments and the everyday ones. Really nice article, Vic.

Excellent find Vic. I've always loved his work.

I like his work