The Strike That Shook America

This coming Monday the U.S. will be celebrating Labor Day. The origins of Labor Day are not a picnic and BBQ, but brutal fighting for the rights of workers. This is one of the strikes that changed America.

CHRISTOPHER KLEIN The power looms that thundered inside the cotton weaving room of the Everett Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts, suddenly fell silent on January 11, 1912. When a mill official demanded to know why workers were standing motionless next to their machines, the explanation was simple: “Not enough pay.”

The weavers who had opened their pay envelopes that afternoon discovered their weekly wages had been reduced by 32 cents. A newly enacted Massachusetts law had reduced the workweek of women and children from 56 to 54 hours, but mill owners, unlike in the past, cut worker’s wages proportionally. For workers who only averaged $8.76 per week, every penny was precious, and 32 cents made the difference between eating a meal or going hungry.

Word of the strike by the women of the Everett Mill swept through Lawrence’s squalid tenements that night, and the following morning the walkout cascaded through neighboring mills. Even above the looms’ deafening din, the shouts of strikers could be heard: “Short pay! All out! All out!” In spite of arctic temperatures, bad blood boiled over. Knife-wielding strikers overwhelmed security gates and slashed machine belts, threads and cloth. They tore bobbins and shuttles off machines. Through the falling snow, rioting workers shattered windows with bricks and ice, and police beat them back with billy clubs. By the end of January 12, more than 10,000 workers were out on strike.

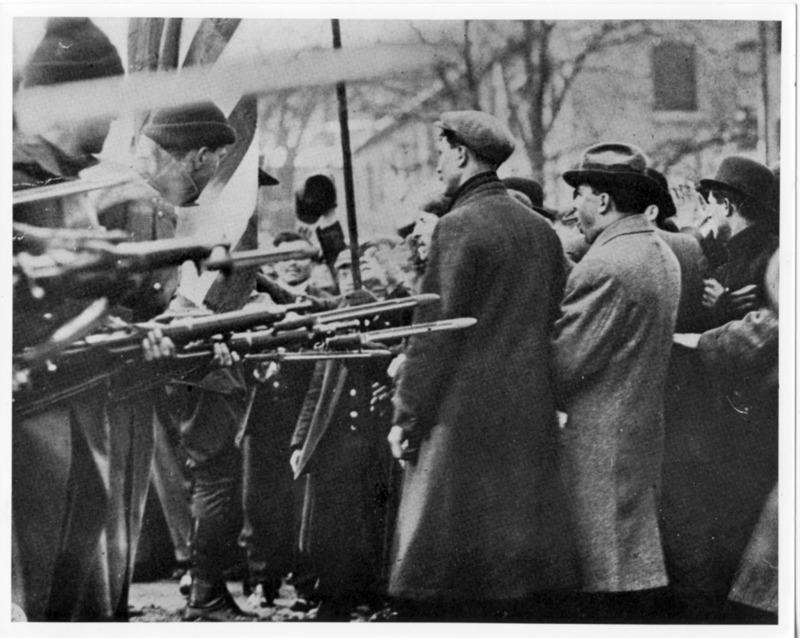

Massachusetts militiamen face strikers in Lawrence.

Their numbers swelled the following week. Thousands of strikers, their numb feet crunching on the snow, chanted and sang protest songs as they paraded through the streets. Picket fences of state militiamen protected the massive brick mills with the spears of their bayonets pointed squarely at the picket lines of strikers who protested outside. Women didn’t shy away from the protests. They delivered fiery rally speeches and marched in picket lines and parades. The banners they carried demanding both living wages and dignity—“We want bread, and roses, too”—gave the work stoppage its name, the Bread and Roses Strike.

Lawrence, known as “Immigrant City,” was a true American melting pot with citizens from 51 nations wedged into seven square miles. Although strikers lacked common cultures and languages, they remained united in a common cause. The social networks of the day—soup kitchens, ethnic organizations, community halls—stitched the patchwork of strikers together. And once news of the walkout went viral in newspapers around the country, American laborers took up collections for the strikers and local farmers arrived with food donations.

Mill owners and city leaders hired men to foment trouble and even planted dynamite in an attempt to discredit strikers. Lawrence’s simmering cauldron finally bubbled over on January 29, when a mob of strikers attacked a streetcar carrying workers who didn’t honor the picket line. That afternoon, as police battled strikers, an errant gunshot struck and killed Anna LoPizzo. The following day, 18-year-old John Ramey died after being stabbed in the shoulder by a soldier’s bayonet.

With the city on a hair trigger, striking families sent 119 of their children out of harm’s way to Manhattan on February 10 to live with relatives or, in some cases, complete strangers who could provide food and a safe shelter. A cheering crowd of 5,000 greeted the children at Grand Central Terminal, and after a second trainload arrived from Lawrence the following week, the children paraded down Fifth Avenue. The “children’s exodus” proved to be a publicity coup for the strikers, and Lawrence authorities intended to halt it. When families brought another 46 children bound for Philadelphia to the city’s train station on February 24, the city marshal ordered them to disperse. When defiant mothers still tried to get their children aboard the train and resisted the authorities, police dragged them by the hair, beat them with clubs and arrested them as their horrified children looked on in tears.

Children who fled Lawrence during the turbulent strike demonstrate in New York City. (Library of Congress)

The national reaction was visceral and marked a turning point in the Bread and Roses Strike. President Taft asked his attorney general to investigate, and Congress began a hearing on the strike on March 2. Striking workers, including children who dropped out of school at age 14 or younger to work in the factories, described the brutal working conditions and poor pay inside the Lawrence mills. A third of mill workers, whose life expectancy was less than 40 years, died within a decade of taking their jobs. If death didn’t come slowly through respiratory infections such as pneumonia or tuberculosis from inhaling dust and lint, it could come swiftly in workplace accidents that took lives and limbs. Fourteen-year-old Carmela Teoli shocked lawmakers by recounting how a mill machine had torn off her scalp and left her hospitalized for seven months.

After the children’s testimony, public tide turned in favor of the strikers for good. The mill owners were ready for a deal and agreed to many of the workers’ demands. The two sides agreed to a 15-percent wage hike, a bump in overtime compensation and a promise not to retaliate against strikers. On March 14, the nine-week strike ended as 15,000 workers gathered on Lawrence Common shouted their agreement to accept the offer. Only five sounded their dissents.

The Bread and Roses Strike was not just a victory for Lawrence workers. By the end of March, 275,000 New England textile workers received similar raises, and other industries followed suit. A century later, the echoes of the strike still reverberate in Lawrence. The city is hosting special centennial commemorations, including its annual Labor Day festival, and Lawrence-based Small Planet Communications has developed a special curriculum for high school history students.

Have a great Labor Day, compliments of the ILWU.

Really interesting article Kavika. I know that in most mills, women and children were abused.

Just 1 year earlier was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in which 23 women and girls and 23 men died from jumping to their death trying to escape the fire since the owners of the factory had chained the doors of the factory shut during work hours. There was no escape. The event lead to the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), which fought for better working conditions for sweatshop workers.

People take for granted that workers get a fair shake, and so "Labor Day" has lost its meaning, but these brave souls made it safe for all of us today who work in factories.

Sadly most do. There were many such strikes that cost the strikers their lives. The Pullman strike of the late 1890's was another. Brutal, resulting in the deaths of dozens of strikers.

It's the reason that the longshoremen have a legal holiday celebrating, ''Bloody Thursday''.

I think the issue that some people get confused is that they think our labor day, is akin to May 1, which is the socialist Labor day. They are nothing alike. Ours comes from our labor not being abused and from a lot of sweat and blood and is not political in origin.

Dear Brother Kavika: "Tzedik tzedik tirdof" ("Justice, justice shall you pursue" - Torah).

Three cheers for the rank and file.

Everyone needs to live n peace, harmony and respect.

Each of us must be the keepers of all our brothers and sisters.

Solidarity is the way to go.

Then, now and going forward.

Great topical and important article.

Thanks for sharing.

P&AB.

Enoch.

The people that fought for worker's rights, at the cost of their lives, and built the American middle class.

Excellent thread and history Kavika. Hopefully, many will read it and actually gain some understanding.

We'll see, it seems that if it isn't about politics/religion not many bother to get informed on important parts of our history.

Interesting seed, Kavika.

Raised as I was in a UMWA household, the union was always a source of conversation in our family. My dad, his father, and 3 of his 4 brothers were all coal miners and members of the UMW. My mom told me some stories about my grampap and his organizing of coal miners. Labor Day was also celebrated as John L. Lewis day where I grew up.

labor activism runs in my family. I still have distant family back in the WV coal mining region.

Excellent.

Many in our family worked in the iron mines of northern Minnesota. Both the underground and open pit.

All union and I can well remember the strikes, and it got very rough for the strikers.

At one time we lived in a company house and bought from the company store.

They were all union members for life.

I grew up in West Virginia, so the WV mine wars of Paint and Cabin Creeks were taught as part of my middle school history classes, and you can see monuments to those wars on any drive through the southern part of the state. More recently, the explosion at the Upper Big Branch Mine showed us why those miners were fighting for not just better wages, but better safety conditions.

There were no coal mines in my county, but the larges employer there when I was growing up was an aluminum plant unionized by the United Steelworkers of America. That's where my dad worked for decades, and there were times during layoffs and a lockout in the nineties that the union paid our mortgage and made sure we kids had a Christmas, in addition to fighting pay and benefits cuts and unfair treatment by supervisors.

I went through 2 contract strikes growing up. Contract strikes can be brutal because they got to get both the union and the coal operators to the table and it can take months before anyone wants to talk. I think Dad got a little something from the union during those times but it wasn't much and Mom went and applied for food stamps so we could eat. Good times.

Our lockout was over a new contract, and it lasted almost 2 years. The union was willing to continue work under the old contract, but were locked out by the company. Because you can't let smelting pots go cold (they'd have to be replaced entirely), the company brought in scabs (and yeah, I'm going to flat-out call them scabs, because they were) to keep the plant operating. At the end of it all, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that the company had bargained in bad faith and engaged in unfair labor practices, but the union never got any back pay for those 20 months they were locked out of their jobs.

It tore the county apart. Businesses closed for several reasons - nobody had extra money to spend, and if any business was found to be supporting the aluminum company or the scabs was boycotted. People who were friends outside of work lost their friends because they fell on opposite sides of the union/management line.

Mom and dad both found minimum-wage jobs, so we didn't qualify for food stamps, but they didn't make enough to pay the mortgage, either. The union helped a bit with that, and also ran a food pantry, so their wages stretched farther. I remember one Christmas getting a Christmas package from the union - some perfume, a sweater (I think). Mom and Dad bought us some small gifts, too. It ran into my senior year, when I was applying for colleges, and I had to apply for the application fees to be waived, because we couldn't afford them. Needless to say, my parents couldn't put any money away for college for me or my siblings.

Scabs....not a dirty word in my house. It was used often. My dad almost went to jail because of scabs. Two of my uncles did go to jail for that reason (same incident)

Here's another great union song:

Which Side Are You On?

______________

" Which Side Are You On? " is a song written in 1931 by Florence Reece, the wife of Sam Reece, a union organizer for the United Mine Workers in Harlan County, Kentucky.

Background

In 1931, the miners and the mine owners in southeastern Kentucky were locked in a bitter and violent struggle called the Harlan County War. In an attempt to intimidate the family of union leader Sam Reece (Cont'd HERE)

I believe a part of the reason we are still in business and employing hundreds of middle class workers is because we were able to keep the union out. Almost all of our union competition has gone out of business and their work went overseas as the union priced them out of competition. Maybe the unions did some good years ago but everything I saw out of them was bad news for the businesses they hurt and ultimately the members as they priced themselves out of global competition.

Dean,

I think there is good and bad with unions. It just really depends on the union. My dad worked for two unions at Republic and Fairchild and there were walkouts over over pay and ultimately he lost his job at both. When he went to work at Grumman, there was no union because Grumman sold the idea that they were a "family". It was all fine and dandy until they lost a bid, made my dad make a choice of losing his job or taking a demotion (he took the demotion), and then when he retired, they cut his pension and health insurance. If he was in a union, that would have never happened.

Usually business thrives at the cost of their workers.

So the one take away I got, was never worked for the man, but not everyone can do that, and they need some protection, too. btw, when I was a teacher I was part of the UFT and I really don't think they did much in either direction.

And there were some great songs that came out of the struggle,

Union Maid

BANKS OF MARBLE

(This video has some excellent historical photos BTW)