The rise and fall of the Jack Daniel’s committee: How D.C.’s police lodge made thousands selling whiskey online

Category: Other

Via: hallux • 4 years ago • 6 commentsBy: Peter Hermann, David A. Fahrenthold and Dana Hedgpeth - WaPo

They were selling whiskey on the Internet.

It was called the Jack Daniel’s Fundraising Committee.

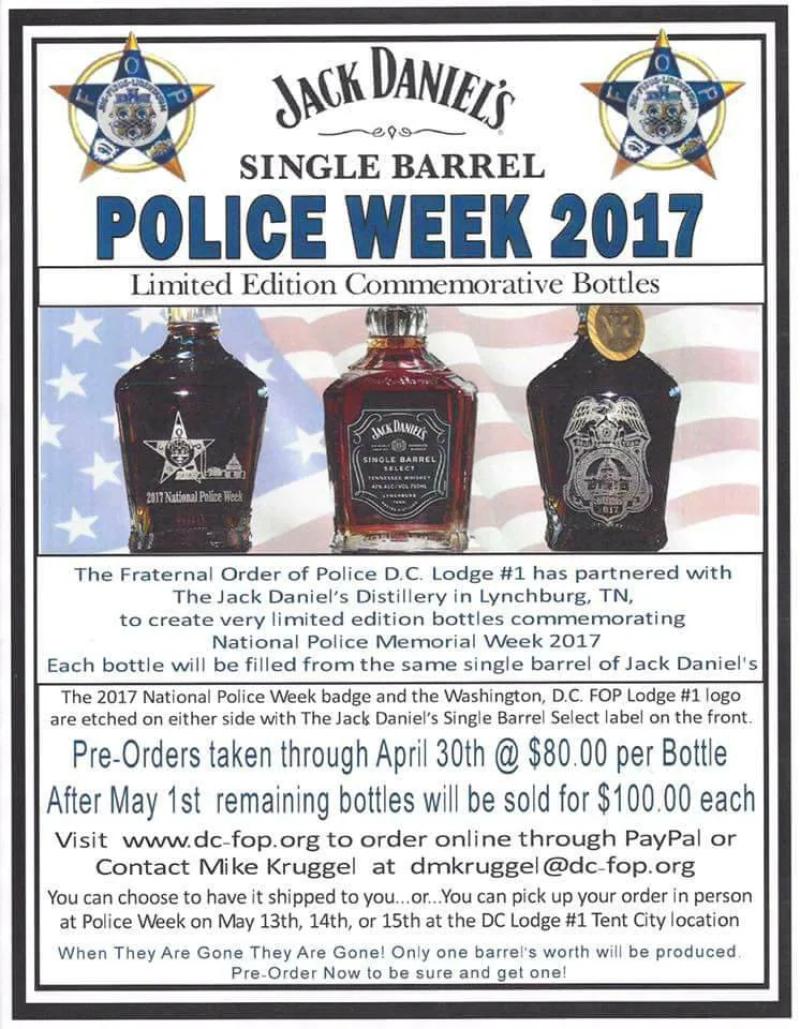

The lodge’s leaders were buying Jack Daniel’s whiskey, engraving the bottles with a police-union logo, then reselling them online at the marked-up price of $80. They’d been overwhelmed with orders.

“$38,000 has been collected, just on PayPal,” said Marcello Muzzatti, a retired D.C. police officer and the lodge’s past president, according to a recording of the meeting.

One of the few non-police officers in the room spoke up.

“Is this, like, legal?” said the woman, who union leaders said was a paralegal.

“Yes. Absolutely,” said Andy Maybo, then the lodge’s president, who made the recording and shared it with The Washington Post.

The Jack Daniel’s committee was a go.

Over the next three years, the D.C. lodge — a group of active and retired police officers, working from a clubhouse near the FBI Field Office — sold more than 3,000 bottles of whiskey to people across the country, according to internal lodge documents and interviews with lodge leaders.

But the sale of hard liquor is tightly regulated — the shipment of hard liquor even more so. And The Post could find no evidence that the lodge ever obtained the permits required to do what it did: sell liquor by the bottle, and ship it across state lines.

“All Jack Daniel's bottled beverages were sold illegally without the proper licensing and shipped in violation of the law,” the lodge’s own internal inquiry concluded in 2020.

The whiskey-selling operation was run by a man named Michael Kruggel, who had become an officer at the D.C. lodge despite working as a security guard at a Tennessee Walmart. Under him, the Jack Daniel’s committee took in more than $500,000 — but spent nearly all of it on expenses and travel, according to the lodge’s internal inquiry. Kruggel, lodge records showed, submitted reimbursements for 72,706 miles of driving in two years, enough to circle the earth 2.9 times.

The Jack Daniel’s committee was shut down last year, when a new slate of officers took over the D.C. lodge. They commissioned an internal report that said the sales, if discovered, could jeopardize the lodge’s nonprofit status and the liquor license for its restaurant. Now, the D.C. lodge is stacked with cases of unsold whiskey.

So far, neither the lodge nor the leaders of the Jack Daniel’s committee have faced legal consequences. The D.C. police investigated, but prosecutors declined to file charges. Now, D.C. alcohol regulators say they are investigating and will report their findings later this month.

The story of the Jack Daniel’s committee suggests how police unions can occupy a bubble of perceived impunity, right next to the law. Even now, some involved in the liquor sales say they’re not convinced they were improper.

“If it was ever against the law, we would never have done it,” said Maybo, the former lodge president, in a recent interview. After all, he said, the whole thing was done by police officers, in front of police officers. “I would imagine that if I’m doing something illegal, if the FOP were doing something illegal, somebody would have said that. And it went on for years.”

Experts in alcohol law said the Jack Daniel’s committee’s actions appeared to be a clear-cut violation of the law in D.C. and multiple states.

“These are cops?” asked Michael Brill Newman, who leads the alcoholic-beverage team at the firm Holland & Knight.

“That’s selling alcohol without a license, and it’s a crime,” said Will Cheek III, a Nashville attorney specializing in liquor regulations.

Illegal shipment of liquor is a misdemeanor or even a felony in some states. But legal experts said it’s rare that anyone faces jail time for illegal alcohol sales.

Instead, offenders typically face civil penalties, like a fine, a lawsuit or a revocation of an existing liquor license — which could be devastating to the financially shaky D.C. lodge.

Cheek said that the D.C. lodge’s operation seemed to violate laws meant to stop minors from obtaining alcohol through the mail: “It goes right back to bootlegging. It’s like opening your trunk and selling out of your trunk.”

Kruggel, who led the Jack Daniel’s committee, responded to questions through an attorney, Michael Bruckheim.

“Mr. Kruggel categorically denies all allegations of wrongdoing with respect to his participation with this committee,” Bruckheim said. Kruggel, like others involved in the committee, blamed rival factions within the lodge for raising doubts about the committee: “The ongoing efforts of these rogue D.C. FOP members who continue to sling false allegations publicly will be met with litigation against both the D.C. FOP and these members individually.”

The Jack Daniel’s committee started at a time of financial problems at the D.C. lodge — a state-level outpost of the country’s largest police lodge. The D.C. lodge, with 9,500 members, includes the labor unions for all the city’s major local and federal police departments. But the lodge itself doesn’t handle labor contracts and bargaining. Instead, it offers broader services to officers, such as a legal-defense plan, social events and a clubhouse where officers could eat breakfast near D.C. Superior Court.

By spring 2017, however, a change in court procedure meant that far fewer officers needed to testify in person. No officers, no breakfasts. The lodge was bleeding money.

“When we closed the restaurant, we had to unfortunately let two of our employees go. These employees had 25-plus years up here, each,” Maybo — then the lodge president — told the members at the March 2017 meeting. He had shuttered the clubhouse’s restaurant and cut its bar back to three nights a week. He had sold the car reserved for lodge presidents.

But, in the midst of that crisis, the lodge allowed Kruggel to try out a new idea.

Whiskey.

The lodge bought a 53-gallon barrel of whiskey for $11,000 at the Jack Daniel’s distillery in Lynchburg, Tenn. The distillery put that whiskey into 240 bottles, and Kruggel had them engraved with the D.C. lodge’s logo. The lodge advertised the bottles on Facebook, with a link to pay via PayPal; buyers could have the bottles shipped or pick them up at an annual police convention in D.C.

Kruggel said the lodge’s leaders wanted to see if he could sell 138 bottles, and recoup their initial investment. They gave him 30 days.

He did it in two.

“As of 40 hours into the sale, we had sold 297 bottles. Which is phenomenal, ” Kruggel said at the March 2017 meeting. The lodge had now ordered three more barrels, officials told the members, to keep up with the surging demand.

“Guys,” Kruggel said, “We make between $8,000 and $10,000 per barrel.”

Kruggel, a jovial 57-year-old, had an unusual background for an officer of the D.C. lodge. For one thing, he lived 670 miles away in Tennessee. For another: The D.C. lodge’s bylaws say that members must be active or retired police from departments headquartered in Washington.

But Kruggel wasn’t, and never had been. He had last been a full-time police officer in California: from 1987 to 1990, Kruggel worked for the now-defunct Los Angeles Community College District police, according to state records.

Since then, Kruggel has worked as a security guard and private investigator. He is a security officer at a Walmart in Nashville, his attorney said.

Kruggel also serves as an unpaid volunteer deputy with the small sheriff’s department in Morgan County, Tenn., two and a half hours from Nashville. The sheriff there, Wayne Potter, said that Kruggel usually works on weekends, riding with a friend of Kruggel’s who is a narcotics officer.

“He has good communication skills, and he is very neatly dressed,” the sheriff said. “I have not had any complaints on him.” He was not aware of the allegations about the Jack Daniel’s committee until The Post called.

Long after Kruggel left his last full-time police job, he became deeply involved in police unions.

That appears to have begun in Nashville, where around 2006, the Teamsters and the Fraternal Order of Police were in the middle of a bitter fight over which union would represent the city’s police. Kruggel was an organizer for the Teamsters, which he’d joined as a security guard in California. But in Nashville, records show, he switched over to the Fraternal Order of Police, which eventually won the fight.

As it happened, Nashville was also the home of the Fraternal Order of Police national headquarters, called the Grand Lodge. Kruggel worked at the headquarters in 2007 and 2008, and got to know Patrick Yoes — a Louisiana officer who was then the national secretary and a rising star.

“I know Mike to be a very passionate and very hard-working individual, and I’ve seen his generosity to people quite often,” Yoes said in a recent interview. On Facebook, Yoes posted photos of himself and Kruggel at a parade, restaurants and Fraternal Order of Police events.

In 2010, Kruggel joined the Fraternal Order of Police D.C. lodge. Bruckheim, Kruggel’s attorney, said that the lodge’s leaders approved it. He said Kruggel had planned to move to D.C. but changed his mind.

“We don’t know how he got to be a member,” said Gerald Neill Jr., a retired D.C. police officer and the lodge’s current president. “Officially, we don’t know how that happened.”

While leading the Jack Daniel’s committee, Kruggel gained a more prominent role at the lodge. He got the President’s Award for volunteer service. He got a column in the newsletter, which he used to warn officers that Jack Daniel’s bottles were selling out fast.

“I don’t want you to be the one left out,” he wrote .

In 2017, Kruggel — who had no police powers in Washington — also got a D.C. government-issued “Authorized Emergency Vehicle” sign for his car, according to the D.C. Department of Motor Vehicles. That allowed him to use emergency lights and a police siren in the city. His attorney said it was related to his work for the lodge.

Revenue from the Jack Daniel’s committee soared, from $124,000 in 2017 to $179,000 in 2018, according to internal lodge documents. The committee added new, more expensive bottles: one for the Washington Capitals’ Stanley Cup win, one for the holidays and a “Ladies Only Bottle.”

At Jack Daniel’s, spokesman Svend Jansen said the distillery knew the lodge was reselling these bottles of whiskey but assumed they were doing so legally — “given the fact this was a law enforcement” organization.

But as revenue increased, so did the Jack Daniel’s committee’s expenses — fast enough to consume nearly all of the money the committee made.

In 2018, lodge records show, about $42,000 went to Kruggel himself, as reimbursement for his claimed expenses. The records show he obtained reimbursement for 84 nights in hotel rooms and 35,159 miles of driving, saying he had traveled to sell Jack Daniel's at police conferences, to transport bottles to be shipped or engraved or to sell other lodges on starting their own Jack Daniel’s committees.

One particularly long trip, according to lodge records, took him from Pensacola, Fla., to Nashville to Washington to Nashville to Lynchburg to Nashville to Pensacola again, for a total of 2,376 miles.

Kruggel’s attorney, Bruckheim, said Kruggel did not control the Jack Daniel’s committee’s spending directly: He had to apply to the lodge’s treasurer to be reimbursed. Bruckheim said Kruggel believed the lodge’s figures about his mileage were inaccurate but he no longer had the records to prove it.

The lodge’s other top officers, who outranked Kruggel, also seemed to benefit from the Jack Daniel’s committee. Some posted photos of themselves in Lynchburg, where Jack Daniel’s allows big customers — those who buy whiskey by the barrel — to visit for special tours and tastings.

“Jack Daniel’s Selection committee,” wrote Robert Berretta, the lodge’s vice president at the time, on Facebook in 2019 next to a photo of himself, Kruggel and seven others in Jack Daniel’s barrel-filled warehouse. Berretta’s next photo showed eight glasses with whiskey samples: “Eeny, meeny, miny, mo . . . ” he wrote .

Lodge records show that Kruggel charged the lodge repeatedly for his own travel to Lynchburg. In an interview, Berretta said the lodge had paid for his travel as well, since he was carrying out his duties as a lodge officer: “We’re making an investment in a barrel.”

After the barrels were chosen, Kruggel took delivery of the whiskey in bottles, then took the bottles to locations in Tennessee to be engraved.

Then, the lodge’s internal inquiry found, Kruggel sold some of the engraved bottles in person, from booths set up at police conventions in D.C., Tennessee, Louisiana and other states. And he sold some over the Internet, taking payment via PayPal and shipping the bottles, according to lodge records.

He had, in effect, entered the lodge into the highly regulated business of selling liquor by the bottle.

But he does not appear to have obtained the licenses required to do it legally.

In the District, for instance, selling liquor by the bottle requires an “ off-premises retailer ” license. But the lodge did not have one : It had only a “club” license, which limits the lodge to selling liquor by the drink in its restaurant. In Tennessee, Louisiana and New Jersey, where the lodge’s investigation found Kruggel sold bottles at police conventions, authorities said they could find no evidence he’d obtained a permit to do so.

Shipping liquor across state lines is even more restricted: 44 states ban it entirely. By talking to buyers, The Post found that the D.C. lodge had shipped Jack Daniel’s to consumers in at least three of those states: Georgia, Iowa and Maryland.

“I wanted to support the FOP,” said Timothy Green, 60, a collector of Jack Daniel’s in Woodstock, Ga. He saw the lodge’s ad on Facebook and bought a bottle for $125 in 2019.

Green said he later read on the Internet that only a small fraction of the proceeds had been left over for the D.C. lodge. “It was kind of disappointing,” Green said. “I thought it would go to widows or children, that’s what I thought that group supported.”

The Post also found that the lodge shipped a bottle to a buyer in Florida, where shipping liquor is legal only with a license. The lodge did not have a license, according to state records.

The lodge’s internal report found that the committee did not have permits to sell bottled liquor “anywhere in the United States.”

Did Kruggel believe what they were doing was legal?

His attorney, Bruckheim, responded with a statement that did not directly address the question.

“Anything done by the Jack Daniel’s Fundraising committee were done as a DC FOP Lodge #1 event and not just one person. This was done at the direction of and with the APPROVAL of the Board of Directors and the General Membership,” Bruckheim wrote.

In recent interviews, two former lodge officials who oversaw the committee said they still weren’t convinced the sales violated the law.

“I don’t know about that,” said Muzzatti, a past president and recording secretary at the lodge. “Is it illegal? You’ve got to ask ABRA,” or Alcoholic Beverage Regulation Administration, the D.C. liquor-control authority.

Maybo, who was president when the whiskey sales began, said he thinks he was right to say the commmittee’s activities were legal.

“I think it was the right answer,” he said. “And to this day I haven’t seen anything otherwise.”

As sales grew, Kruggel also used the committee’s money to give the D.C. lodge — and himself — a higher profile on the national stage.

When the Fraternal Order of Police board met in New Orleans in 2019, the Jack Daniel’s committee paid $17,500 to put on a dinner at the National World War II Museum. One of the speakers was Yoes — Kruggel’s friend from Tennessee, then running to become the union’s national president.

Berretta, the D.C. lodge vice president, also spoke. At the front of the room, there was a huge photo of Kruggel, welcoming everyone in the name of the Jack Daniel’s committee. It was a remarkable turnabout: just two years after the Jack Daniel’s committee began, it had put a volunteer police officer from Tennessee — and lodge so broke it couldn’t afford a car — at the center of the police union world.

“Please buy more Jack Daniel’s !!,” wrote Berretta , as he posted photos of the event on Facebook.

But at its moment of greatest success, both Kruggel and the Jack Daniel’s committee began to attract questions within the lodge. Critics in the lodge questioned Kruggel’s police credentials, and — in one dramatic incident in 2019 — one of them even called the D.C. police’s elite Gun Recovery Unit, saying that Kruggel was carrying a gun illegally.

According to a D.C. police report, officers came to the lodge and found that Kruggel was indeed carrying a gun. But they left after talking by phone to Potter, the Morgan County, Tenn., sheriff, and verifying that Kruggel was a reserve police officer, the report said. Kruggel was not charged.

The next lodge’s presidential election, in November 2019, was won by Neill, the retired D.C. police officer. Neill said he’d campaigned in part on seeking answers about the Jack Daniel’s committee.

After taking over in January 2020, he asked a retired D.C. police homicide detective, Lorren Leadmon, to investigate.

Leadmon’s report, issued in summer 2020, was scathing. It said the committee had taken in roughly $516,000 over three years, but — because of “extremely excessive expenditures” — it had only produced $11,000 in net revenue for the lodge.

Leadmon blamed both Kruggel and the leaders of the lodge.

“At no time did anyone of these individuals put a stop to this misconduct or obtain the proper licensing,” he wrote. Leadmon died in February 2021.

Earlier this year, Neill sent out Leadmon’s report to the lodge’s mailing list, which includes thousands of email addresses. The D.C. lodge voted this year to expel Kruggel, Neill said. Kruggel’s lawyer said he is appealing.

In response to allegations about the committee, the national Fraternal Order of Police board placed the D.C. lodge under “national oversight” and will recommend ways to improve its in-house financial controls, Yoes said.

Yoes is now the Fraternal Order of Police national president. In an interview, he said he had allowed Kruggel to use the national organization’s warehouse, but he assumed Kruggel was handling the legal questions.

“I knew that it was Jack Daniel’s,” Yoes said. “They were operating a D.C. lodge under their permits, and since it had nothing to do with us, I never got involved.”

Yoes said he had been cleared of wrongdoing by the national union board.

So far, it appears that no one has faced legal consequences as a result of the committee. A D.C. police spokeswoman, Kristen Metzger, said that officers from the financial crimes section had investigated allegations about the Jack Daniel’s committee in October 2020. They presented their finding to the U.S. attorney’s office, Metzger said, but prosecutors found that the records about the committee were too scant to reach a conclusion.

“The documentation was insufficient to present a finding,” Metzger said. “Based on that issue, the United States Attorney’s Office decided not to move forward.”

Bill Miller, a spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office in the District, said the office “typically does not confirm or deny investigations and has no comment regarding this matter.”

ABRA, the D.C. liquor agency, said it was investigating after receiving an anonymous tip in the mail.

Now, questions about the Jack Daniel’s committee have become a major issue in its lodge’s next elections, set for Nov. 10. Muzzatti is running for president again. One of his opponents is Trevor Hewick, a former D.C. officer whose campaign fliers say the committee is proof that “DC Lodge #1 has lost its way!!!”

In the meantime, Neill — the lodge’s current president — said the Jack Daniel’s committee, intended as a fundraiser, had left the lodge just as broke.

In March 2020, after the Jack Daniel’s committee was shut down, lodge leaders discovered more than 1,000 liquor bottles stored around the clubhouse. There were 300 more bottles in the national Fraternal Order of Police warehouse in Nashville — so much that the lodge needed a special permit just to drive it back to Washington.

In all, the D.C. lodge was left with 1,425 bottles of Jack Daniel’s, the unsold remnants of the Jack Daniel’s committee.

How long will it take them to sell that whiskey legally?

Well, the bar is open three nights a week.

“We’re better than $200,000 in arrears. How the hell does that happen?” Neill said. On the floor of his office, and on top of his couch, were cases of Jack Daniel’s whiskey

Seeing as I bought drugs from the police (they had the best stuff) in the 1970s, I have no comment pro or con.

bwah ha ha, so did I. $80 for over a pound, straight out of the police evidence locker. thanks benny!

MP's were my go to guys. They hated the paperwork if they caught someone with weed so they would just turn around and sell it.

To serve, protect and make an illegal buck. The new LEO motto.

... ignorance of the law is no excuse. put the bracelets on them...

Trust a guy from Tennessee to know how to bootleg...using the internet