The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More

Jeff Campbell worked for 20 years as a criminal investi gator for the state of New Mexico. He specialized in cold cases. These days, he applies his sleuthing skills to a case so cold it’s buried beneath a century and a half of windblown prairie.

“Here’s the crime scene,” Campbell says, surveying a creek bed and miles of empty grassland. A lanky, deliberate detective, he cups a corncob pipe to light it in the flurrying snow before continuing. “The attack began in predawn light, but sound carries in this environment. So the victims would have heard the hooves pounding towards them before they could see what was coming.”

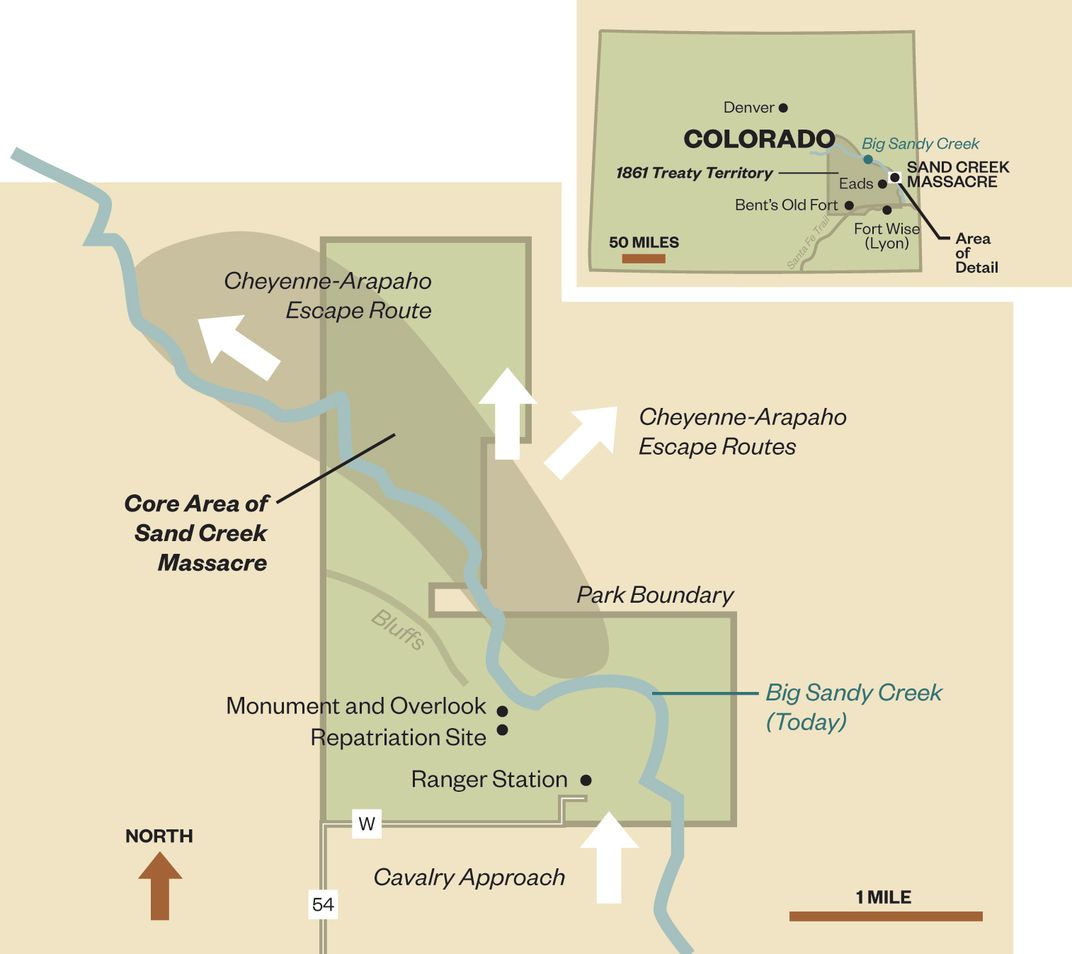

Campbell is reconstructing a mass murder that occurred in 1864, along Sand Creek, an intermittent stream in eastern Colorado. Today, less than one person per square mile inhabits this arid region. But in late autumn of 1864, about 1,000 Cheyenne and Arapaho lived in tepees here, at the edge of what was then reservation land. Their chiefs had recently sought peace in talks with white officials and believed they would be unmolested at their isolated camp.

When hundreds of blue-clad cavalrymen suddenly appeared at dawn on November 29, a Cheyenne chief raised the Stars and Stripes above his lodge. Others in the village waved white flags. The troops replied by opening fire with carbines and cannon, killing at least 150 Indians, most of them women, children and the elderly. Before departing, the troops burned the village and mutilated the dead, carrying off body parts as trophies.

There were many such atrocities in the American West. But the slaughter at Sand Creek stands out because of the impact it had at the time and the way it has been remembered. Or rather, lost and then rediscovered. Sand Creek was the My Lai of its day, a war crime exposed by soldiers and condemned by the U.S. government. It fueled decades of war on the Great Plains. And yet, over time, the massacre receded from white memory, to the point where even locals were unaware of what had happened in their own backyard.

That’s now changed, with the opening of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. “We’re the only unit in the National Park Service that has ‘massacre’ in its name,” says the site’s superintendent, Alexa Roberts. Usually, she notes, signs for national historic sites lead to a presidential birthplace or patriotic monument. “So a lot of people are startled by what they find here.”

Visitors are also surprised to learn that the massacre occurred during the Civil War, which most Americans associate with Eastern battles between blue and gray, not cavalry killing Indians on the Western plains. But the two conflicts were closely related, says Ari Kelman, a historian at Penn State University and author of A Misplaced Massacre , a Bancroft Prize-winning book about Sand Creek.

The Civil War, he observes, was rooted in westward expansion and strife over whether new territories would join the nation as free states or slave states. Slavery, however, wasn’t the only obstacle to free white settlement of the West; another was Plains Indians, many of whom staunchly resisted encroachment on their lands.

When the Park Service and tribal leaders clashed over the exact location of the tragedy, Campbell concluded both were right: the massacre spread out over an area of 12,500 acres. Jamie Simon

When the Park Service and tribal leaders clashed over the exact location of the tragedy, Campbell concluded both were right: the massacre spread out over an area of 12,500 acres. Jamie Simon “We remember the Civil War as a war of liberation that freed four million slaves,” Kelman says. “But it also became a war of conquest to destroy and dispossess Native Americans.” Sand Creek, he adds, “is a bloody and mostly forgotten link” between the Civil War and the Plains Indian Wars that continued for 25 years after Appomattox.

One reason Sand Creek remains little known is its geographic remoteness. The site lies 170 miles southeast of Denver, in a ranching county that never recovered from the Dust Bowl. The nearest town, Eads, is a dwindling community of about 600 that can field only a six-man high-school football team. The unpaved, eight-mile road leading to Sand Creek crosses short-grass prairie that appears almost featureless, apart from a few cattle and a grain silo 30 miles away in Kansas, visible on clear days.

The historic site also offers few landmarks: a visitors center housed, for now, in a trailer, an Indian graveyard and a monument atop a low bluff beside Sand Creek, a narrow stream fringed by willow and cottonwood. “It was treeless here in 1864 and the creek was mostly dry by late November,” says Campbell, the criminal investigator, who is now a seasonal ranger at the site. No trace of the village site or massacre remains, apart from bullets, artillery fragments and other relics dug from decades of windblown dirt by archaeologists.

While visible evidence of the crime is scarce, the “witness pool,” as Campbell calls it, is unusually large. Indian survivors drew maps of the attack, painted it on elk hides and told of the massacre to their descendants. But for white Americans at the time, the most damning testimony came from soldiers, who not only described the massacre but also fingered their commanding officer, a larger-than-life figure regarded, until then, as a war hero and rising star.

John Chivington stood 6-foot-4, weighed over 200 pounds, and used his booming voice to good effect as a minister and ardent abolitionist before the Civil War. When war broke out, he volunteered to fight rather than preach, leading Union troops to victory at Glorieta Pass, in New Mexico, against a Confederate force that sought to disrupt trade routes and invade the Colorado gold fields.

That 1862 battle—later hailed as the “Gettysburg of the West”—ended the Rebel threat and made Chivington a colonel. But as Colorado troops deployed east, to more active campaigns, conflict increased with Indians in the thinly settled territory. Tensions peaked in the summer of 1864, following the murder of a white family near Denver, a crime attributed at the time to raiding Cheyenne or Arapaho. The territorial governor, John Evans, called on citizens to “kill and destroy” hostile natives and raised a new regiment, led by Chivington. Evans also ordered “friendly Indians” to seek out “places of safety,” such as U.S. forts.

The Cheyenne chief Black Kettle heeded this call. Known as a peacemaker, he and allied chiefs initiated talks with white authorities, the last of whom was a fort commander who told the Indians to remain in their camp at Sand Creek until the commander received further orders.

But Governor Evans was intent on the “chastisement” of all the region’s Indians and he had a willing cudgel in Chivington, who hoped further military glory would vault him into Congress. For months, his new regiment had seen no action and become mockingly known as the “Bloodless Third.” Then, shortly before the unit’s 100-day enlistment ran out, Chivington led about 700 men on a night ride to Sand Creek.

“At daylight this morning attacked Cheyenne village of 130 lodges, from 900 to 1,000 warriors strong,” Chivington wrote his superior late on November 29. His men, he said, waged a furious battle against well-armed and entrenched foes, ending in a great victory: the deaths of several chiefs, “between 400 and 500 other Indians” and “almost an annihilation of the entire tribe.”

This news was greeted with acclaim, as were Chivington’s troops, who returned to Denver displaying scalps they’d cut from Indians (some of which became props in celebratory local plays). But this gruesome revelry was interrupted by the emergence of a very different storyline. Its primary author was Capt. Silas Soule, a militant abolitionist and eager warrior, like Chivington. Soule, however, was appalled by the attack on Sand Creek, which he saw as a betrayal of peaceful Indians. He refused to fire a shot or order his men into action, instead bearing witness to the massacre and recording it in chilling detail.

“Hundreds of women and children were coming towards us, and getting on their knees for mercy,” he wrote, only to be shot and “have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.” Indians didn’t fight from trenches, as Chivington claimed; they fled up the creek and desperately dug into its sand banks for protection. From there, some young men “defended themselves as well as they could,” with a few rifles and bows, until overwhelmed by carbines and howitzers. Others were chased down and killed as they fled across the Plains.

Soule estimated the Indian dead at 200, all but 60 of them women and children. He also told of how the soldiers not only scalped the dead but cut off the “Ears and Privates” of chiefs. “Squaws snatches were cut out for trophies.” Of Chivington’s leadership, Soule reported: “There was no organization among our troops, they were a perfect mob—every man on his own hook.” Given this chaos, some of the dozen or so soldiers killed at Sand Creek were likely hit by friendly fire.

Soule sent his dispatch to a sympathetic major. A lieutenant at the scene sent a similar report. When these accounts reached Washington in early 1865, Congress and the military launched investigations. Chivington testified that it was impossible to tell peaceful from hostile natives, and insisted he’d battled warriors rather than slaughtering civilians. But a Congressional committee ruled that the colonel had “deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre” and “surprised and murdered, in cold blood” Indians who “had every reason to believe that they were under [U.S.] protection.”

That authorities in Washington paid attention to distant Sand Creek was striking, particularly at a time when civil war still raged back East. Federal condemnation of a military atrocity against Indians was likewise extraordinary. In a treaty later that year, the U.S. government also promised reparations for “the gross and wanton outrages” perpetrated at Sand Creek.

Chivington escaped court-martial because he had already resigned from the military. But his once-promising career was over. He became a nomad and failed entrepreneur rather than a Congressman. Soule, his principal accuser, also paid for his role in the affair. Soon after testifying, he was shot dead on a Denver street by assailants believed to have been associates of Chivington.

Another casualty of Sand Creek was any remaining hope of peace on the Plains. Black Kettle, the Cheyenne chief who had raised a U.S. flag in a futile gesture of fellowship, survived the massacre, carrying his badly wounded wife from the field and straggling east across the wintry plains. The next year, in his continuing effort to make peace, he signed a treaty and resettled his band on reservation land in Oklahoma. He was killed there in 1868, in yet another massacre, this one led by George Armstrong Custer.

Many other Indians, meanwhile, had taken Sand Creek as final proof that peace with whites was impossible and promises of protection meant nothing. Young Cheyenne warriors, called Dog Soldiers, joined other Plains tribesmen in launching raids that killed scores of settlers and paralyzed transport. As a result, says the historian Ari Kelman, the massacre at Sand Creek accomplished the opposite of what Chivington and his allies had sought. Rather than speed the removal of Indians and the opening of the Plains to whites, it united formerly divided tribes into a formidable obstacle to expansion.

Sand Creek and its aftermath also kept the nation at war long after the South’s surrender. Union soldiers, and generals such as Sherman and Sheridan, were redeployed west to subdue Plains Indians. This campaign took five times as long as the Civil War, until the infamous massacre at Wounded Knee, in 1890, all but extinguished resistance.

“Sand Creek and Wounded Knee were bookends of the Plains Indian Wars, which were, in turn, the last sad chapter of the Civil War,” Kelman says.

Sand Creek also left an open wound among the Cheyenne and Arapaho, who were ultimately driven onto distant reservations in Oklahoma, Wyoming and Montana. The reparations promised them in 1865 were never paid. And Sand Creek gradually morphed in white memory, from a massacre condemned by the U.S. to a “battle,” etched on the 1909 Civil War monument by the Colorado statehouse, alongside victories like Glorieta Pass. Many sites in Colorado were named for Chivington, Governor Evans and other players in the massacre. The scalp of an Indian killed at Sand Creek remained on display at the state historical museum until the 1960s.

“For many years, the story of Sand Creek was told as a triumph of civilization and a founding victory of Colorado,” says William Convery, the state’s official historian. “Then the story wasn’t told, even in school. It nearly vanished.”

Over the past 16 years, Sand Creek has been reclaimed by Coloradans, but not without heated controversy. When History Colorado, the state’s new historical museum in Denver, decided to include Sand Creek among its inaugural exhibits, some donors and veterans’ groups complained. “They worried we’d portray the state and the military in a bad light,” says Convery, who is director of exhibits at the museum. “A lot of people feel this is a place to celebrate Colorado and wonder why we’re dwelling on the negatives.”

But in the view of many Indians, the exhibit that opened in 2012 wasn’t negative or truthful enough. In particular, tribal leaders objected to the exhibit’s title, “Collision,” which makes Sand Creek sound like a no-fault car accident rather than a massacre.

The museum revised the exhibit and added material such as videotaped interviews with tribal elders. But the furor continued, causing History Colorado to close the exhibit in June 2013.

Two universities have joined the fray over memory of Sand Creek. John Evans, the territorial governor who encouraged Chivington in his campaign against natives, was a leading founder of both the University of Denver and Northwestern University in Evanston, the Illinois city named for him. Both schools recently appointed committees to study Evans’ involvement in Sand Creek and determine whether he and the universities were financial beneficiaries of the massacre. Northwestern’s study, released last May, found that Evans didn’t plan the massacre, but his defense of it “warrants condemnation” and both he and the university profited from the economic development that accompanied whites displacing Indians on the Plains.

Angry debate has also dogged the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, which was mandated by Congress in 1998 but didn’t open for almost a decade. Coloradans who disliked the name and mission of the site became particularly vocal after 9/11. To them, it seemed unpatriotic to memorialize a massacre by American troops, particularly at a time when many Colorado residents were serving in Afghanistan and Iraq. One historian challenged the notion that Sand Creek was a massacre at all, and said of Black Kettle, “he was harboring terrorists.”

The Park Service’s efforts to locate the massacre site became another flash point. Longtime ranchers in the area believed they knew where it lay. So did descendants of Cheyenne and Arapaho attacked at Sand Creek. The tribes had long hallowed a bend in the creek marked on a map made by a survivor and identified in subsequent visits by spiritual leaders. But the Park Service mainly relied on government maps and archaeological evidence, which put the massacre more than a half-mile away. The search for the site became a cultural clash, over different notions of history and knowledge, with Indians feeling they were being disrespected and dispossessed yet again.

“This is our history, our elders have always known what happened and where it happened,” says Joe Big Medicine, a Cheyenne descendant. “All people had to do was listen.”

A truce, of sorts, was brokered with the help of Campbell, the criminal investigator, who moved to the area in 2002. For years, he pored over old maps and archival documents, and studied the terrain, weather and other elements. One of his key findings was that the course of the creek had changed over time, accounting for much of the confusion over bends and other features. Also, the massacre spread across miles as Indians fled the initial assault and were chased by troops. In short, areas identified by the Park Service, ranchers and descendants of the victims all had validity and lay within the boundaries of the national historic site, which encompasses some 12,500 acres.

“I won’t call it ‘case closed’ because there are many questions still to answer about how and why the massacre took place,” Campbell says. But tensions have cooled, and the site has been open for seven years now to mostly positive reviews. Local fears that the massacre site might stigmatize the community and invite Indian land claims, even casinos, have not been realized, and some in the area have had their eyes opened to history hidden from them for generations.

“People just called it ‘the Indian battle,’ that’s all we knew,” said one local visitor, Joyce Mayo, who grew up near Sand Creek and didn’t visit the historic site until she was in her 70s. “Something happened here that nobody should have ever did. Which makes me wonder what else happened in our history that we weren’t told about.”

Military personnel stationed in Colorado have been frequent visitors as well, including officers in a combat brigade headed to Afghanistan; for them, Sand Creek offered a harrowing and cautionary lesson about the treatment of native inhabitants. American Indians also come in large numbers, from as far away as Mexico and Canada, leaving turquoise, bundles of sage or tobacco, and other offerings at the base of the bluff-top monument.

“Sand Creek isn’t like Mount Rushmore or the geysers at Yellowstone,” says Karen Wilde, a Native American who works as tribal liaison for the Park Service. “You feel a presence here rather than just taking in the sights.” Sand Creek, she adds, has significance for all tribes, “because this is an example of what happened to so many native people across the land.”

The site has special meaning for the Cheyenne and Arapaho, who hold a ceremony there each November, followed by a “healing run” from Sand Creek to the Colorado statehouse, where the letters of Silas Soule are read aloud. Some of those killed at Sand Creek have also come home, following the repatriation of skulls and scalps by private holders and museums, including the Smithsonian Institution. In 2008, descendants interred these remains at the Sand Creek cemetery, finally burying their dead from 1864—uncounted casualties from the Civil War.

Before the remains were lowered into the ground, a drum group sang the death song of White Antelope, a Cheyenne chief killed at Sand Creek. “Nothing lives long,” he chanted as troops bore down on the village. “Only the earth and the mountains.”

“Hundreds of women and children were coming towards us, and getting on their knees for mercy,” he wrote, only to be shot and “have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.” Indians didn’t fight from trenches, as Chivington claimed; they fled up the creek and desperately dug into its sand banks for protection. From there, some young men “defended themselves as well as they could,” with a few rifles and bows, until overwhelmed by carbines and howitzers. Others were chased down and killed as they fled across the Plains.

Soule estimated the Indian dead at 200, all but 60 of them women and children. He also told of how the soldiers not only scalped the dead but cut off the “Ears and Privates” of chiefs. “Squaws snatches were cut out for trophies.” Of Chivington’s leadership, Soule reported: “There was no organization among our troops, they were a perfect mob—every man on his own hook.”

Tell me that this wasn't/isn't genocide or "White mob rule".

In your history book? Very seriously doubt it 'cause your history don't matter if you're an Indian.