With historical promises in mind, justices weigh state criminal jurisdiction in Indian country

At the last Supreme Court oral argument of Justice Stephen Breyer’s career, the court stepped into a dispute over the state of Oklahoma’s criminal jurisdiction authority in Indian country. After nearly two hours of debate on Wednesday, four justices appeared strongly inclined to vote against Oklahoma, but the rest of the court did not seem so sure.

Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta involves the state’s jurisdiction to prosecute a non-Indian defendant’s criminal neglect of an Indian child with special needs inside of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma’s reservation. The case comes on the heels of the court’s monumental 2020 decision, McGirt v. Oklahoma , which reaffirmed that the reservation of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation within Oklahoma remains “Indian country.” In Indian country, state criminal jurisdiction is limited to crimes involving non-Indians only. Oklahoma courts have extended the McGirt holding to include other Indian reservations, including that of the Cherokee Nation. As a result, most of eastern Oklahoma is now understood to be Indian country — a development that, according to the state, has disrupted the criminal justice system there.

Castro-Huerta ’s legal issues are narrower than those in McGirt . The case depends on whether the General Crimes Act prohibits Oklahoma’s prosecution of non-Indians who commit crimes against Indian victims in Indian country. Enacted in 1948, the GCA extended to Indian country the general federal criminal laws that apply in places where the federal government has exclusive jurisdiction (i.e., federal enclaves). The question is whether the GCA therefore prohibits concurrent state criminal prosecutions.

The justices favoring exclusive federal jurisdiction focused on two kinds of historical context. On the first, broader context, Justice Neil Gorsuch pointedly reminded the state’s advocate, veteran Supreme Court practitioner Kannon Shanmugam, of the promises made by the United States in its treaties with the Cherokee Nation. In those treaties, the United States accepted a duty of protection (usually known as the trust relationship) favoring the Cherokee Nation. Later, in a colloquy with Zachary Schauf, counsel for Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, Gorsuch teased out more specific federal promises, including that “no other sovereign” would have power within the Cherokee lands and that the Cherokee government must consent before state powers would be applicable. Gorsuch noted that the court had stated in older cases that the states were the “deadliest enemies” of tribes and Indians. Gorsuch’s history lesson formed the basis for the general rule that states do not possess powers in Indian country absent congressional authorization.

On the second, narrower historical context primarily advanced by Castro-Huerta, Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor focused on the history of the GCA itself. They pointed out that, for 200 years or so, the court has uniformly noted that the GCA preempts state criminal prosecutions. Shanmugam’s responses on the point attempted to remind the justices that those statements in prior opinions were merely dicta, which drew heated rebukes at times from both Kagan and Gorsuch, the latter of whom stated, “It’s easy enough to say that [states possess inherent powers without congressional authorization], standing on the podium in Washington, D.C.” Kagan added that, given the weight of history and practice, Oklahoma’s ask for concurrent criminal jurisdiction was, alternately, a “big lift,” “completely weird,” and even “bizarre.” When Shanmugam objected to the number of cases actually saying this, Gorsuch insisted the state’s count was “parsimonious.”

Breyer pressed Shanmugam for reasons why Oklahoma couldn’t just go to Congress for relief. He added that, excepting Oklahoma, the other 49 states all acted under a “general assumption” that state jurisdiction was forbidden absent congressional authorization. Sotomayor added that many states have declined to assert jurisdiction in Indian country, an expensive obligation with little or no federal money available to pursue, and that if Oklahoma prevailed here, those states would be shackled with an “unfunded mandate.” Arguing for the United States on the side of Castro-Huerta, Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler, making his 150th argument before the court (a fact noted by the chief justice at the conclusion of the argument), added that the GCA is part of a criminal jurisdiction regime reflective of “sovereign choices by the United States” that are “fundamentally a political decision,” and not for the judiciary to upset.

The justices were more sympathetic to Oklahoma’s views on whether the GCA’s text alone is sufficient to preempt state jurisdiction. The chief justice and the court’s newest justice, Amy Coney Barrett (who was not on the court for McGirt and may be a pivotal vote in this case), seemed intent on reading the GCA in a vacuum, pointing out that the statute does not affirmatively strip states of powers in Indian country. Justice Clarence Thomas suggested that concurrent jurisdiction would not create any “conflict” of the sort that is typically present when the court finds that federal authority pre-empts state authority. Schauf, in an answer later echoed by Kneedler, asserted that the very structure of the Constitution, which strips states of power over Indian country lands, supplies the conflict, citing one of the court’s earliest Indian law decisions, Worcester v. Georgia (1832). Musing on the continued validity of Worcester , the chief justice invoked Justice Felix Frankfurter, who suggested in Organized Village of Kake v. Egan (1962), that Worcester ’s main thrust had been undercut by “subsequent developments.”

The lion’s share of Shanmugam’s presentation involved repeated assertions that the federal government was failing to fill the gap left in law enforcement left by the McGirt decision. In a move unusual for Supreme Court arguments, Sotomayor cited an article published this week in The Atlantic by Rebecca Nagle and Allison Herrera questioning Oklahoma’s assertions that thousands of criminals were roaming free because of McGirt . Even the chief justice wondered if Oklahoma’s repeated invocation of McGirt was just “waving the bloody shirt.” Gorsuch wondered, “Are we to wilt today because of a social media campaign?”

Even so, Justice Samuel Alito pressed Kneedler for evidence that the U.S. Department of Justice’s response was “concrete” and “sustainable.” Alito, joined later by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, suggested that more governments exercising criminal jurisdictional powers would only benefit Indian victims. Gorsuch responded by once again noting that the tribe and the federal government long ago negotiated for federal jurisdiction only and that the GCA should be read with those “treaty promises” in mind.

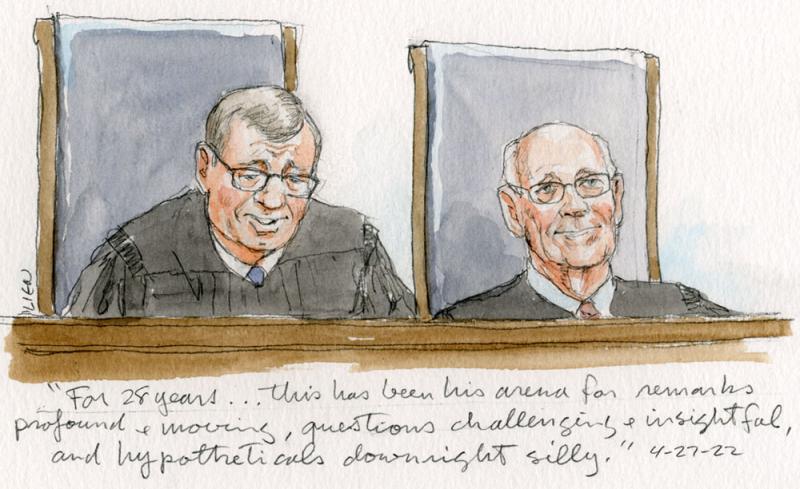

After the conclusion of the argument, an emotional Chief Justice John Roberts fêted Breyer, who is retiring this summer. Roberts jokingly referred to the beloved justice’s hypotheticals (including one just last week about “radioactive muskrats”). “For 28 years,” the chief justice said, “this has been his arena for remarks profound and moving, questions challenging and insightful, and hypotheticals downright silly. … We leave the courtroom with deep appreciation for the privilege of sharing this bench with him.”

The Constitution clearly states that the Feds make Treaties with Tribes/Nations and no one else can.

Criminal jurisdiction for crimes occurring on Indian lands, unless stipulated by Congressional law, is between the tribes/nations/Feds.

The states have no standing over criminal incidents involving non-Indian/Indians on Indian lands UNLESS specifically stipulated by Congress.

OK has lost 29 out of 30 appeals on this particular jurisdiction - and they're getting ready to lose # 30.

True, however, the current court's philosophy seems to be bent on turning everything over to the States.

Not wanting to push this too far off topic; but, with current uproar about abortion I think this is a good question, could a tribe decide abortion is legal and the surrounding state be unable to enforce a law prohibiting abortion?

Good question, charger. IMO, yes they could be based on current law. I believe there was a brief by Harvard law that stated that tribes could prohibit abortion based on their sovereignty so if that is correct then they would have the right to decide abortion is legal even if the surrounding state prohibited it.

I'll do some research on this and see what else I can find.

charger here is a link to the Harvard Law article. Quite interesting.

Thanks, very interesting

The Supreme Court weighing......................

Tell you what. It is past time to make the SCOTUS an elective office, with single 8-year terms. The court is partisan, fraught with inequities, infested with ill equipped/substandard personnel whose main qualifications were "I like beer---Do You Black Out--- placed by a deliberative body that is incapable of deliberating anything substantive and only able of delivering nonsense and mayhem.

The Court of The Supreme Beings? Hell with it. Let the voters decide. After all, the voters are the ones paying for it.

The original McGrit decision was 5-4 with Gorsuch writing the majority decision. There are only two justices on the court that understand US/Indian law and treaties and they are Gorsuch and Sotomayor.

I suspect that the court will rule against Oklahoma. Of course, there is a new addition that knows nothing about treaties/Indian law that could make a mess of this.

Could the jurisdiction possibly just need to be re-visited and a new agreement worked out? Possibly like an agreement similar to what the military has with each state? There seems to be so much confusion with it especially when you look at how much the laws of both the Native American communities and states have changed over the years.