When Sci-Fi Anticipates Reality

“A Spectrum of Futures”

I have some good news for readers of The Daily who are also active in the metaverse (if, indeed, you exist): Legs are on their way. Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook, announced this week that its users would soon be able to add legs to their avatars in the VR versions of Meta Quest’s Horizon Home and Horizon Worlds . Before this update, figures in these virtual worlds were floating torsos that hovered above chairs and whooshed around conference rooms; legs were apparently a much-requested feature. Now the metaverse’s avatars will, in some ways, become more human, while also becoming more uncanny.

Reading about this news, I told my editor—mostly as a joke—that the metaverse users interested in accessing alternative realities and stepping into other lives should consider simply reading a novel. I stand by that cranky opinion, but it also got me thinking about the fact that the metaverse actually owes a lot to the novel. The term metaverse was coined in a 1992 science-fiction novel titled Snow Crash . (The book also helped popularize the term avatar , to refer to digital selves.) And when you start to look for them, you can find links between science fiction and real-world tech all over.

People often say that a new, hard-to-believe piece of technology (like eyeball-scanning orbs ) seems plucked from science fiction. In many cases, the relationship between tech and sci-fi works both ways: Technologists might get ideas from sci-fi movies and books; scientists consult on sci-fi projects to make them more realistic. And creators of both tech and fiction are frequently sharing the same cultural anxieties and references. Sometimes the influence of sci-fi is explicit. The man credited with inventing the first cellphone reportedly drew inspiration from Dick Tracy; the government’s “Gorgon Stare” surveillance-drone technology can apparently be traced back to the Will Smith movie Enemy of the State . The name for the Taser references a young-adult science-fiction novel. The list goes on !

Often, though, the influence of science fiction on tech is less literal. Scientists are not generally reading novels and plucking new concepts for new inventions from them wholesale. But they may use pop-culture references to illustrate their ideas, or refer to science fiction in their research, Philipp Jordan, a lecturer in informatics at the University of Indiana, has found . His work has shown that nods to science fiction in computer-science papers have gone up in recent years, and that computer scientists have used fictional depictions of human-robot relationships—both positive, like with WALL-E, and dystopian, like with Skynet—as reference points in talking about the subject.

Jordan told me that there is a feedback loop between cultural output and technology. Science-fiction movies may reflect widespread fears about new technologies at a given moment—and then the public’s engagement with those films may be fed back into the scientific discourse. “I think [science fiction] is an extremely valuable asset for students, for the next generation of researchers, because it shows us a spectrum of futures, good and bad,” he said.

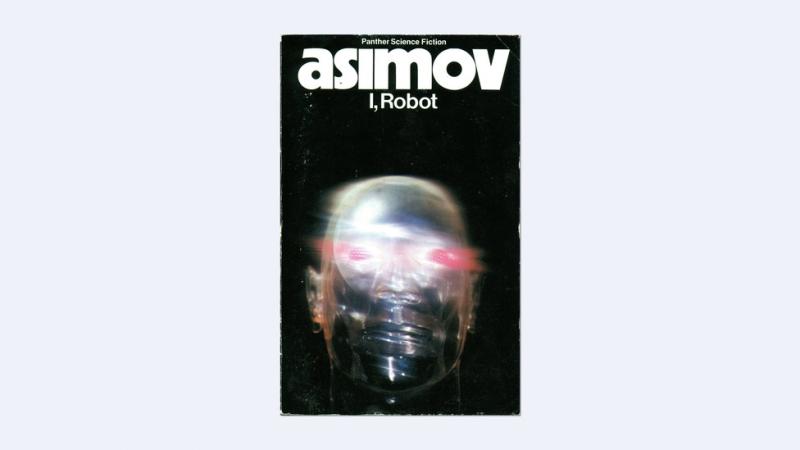

Ross Andersen, an Atlantic writer who covers science and technology, also told me he suspects that “a messy feedback loop” operates between sci-fi and real-world tech. Both technologists and writers who have come up with fresh ideas, he said, “might have simply been responding to the same preexisting human desires: to explore the deep ocean and outer space, or to connect with anyone on Earth instantaneously.” Citing examples such as Jules Verne’s novels and Isaac Asimov’s stories, Ross added that “whether or not science fiction influenced technology, it certainly anticipated a lot of it.”

The pattern of science fiction anticipating, or at least dovetailing with, cutting-edge real-world ideas is not new: In a 2016 article for The Atlantic , Edward Simon explored the sci-fi that was published during and before the peak of the scientific revolution, including such novels as Thomas More’s Utopia , Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis , and Johannes Kepler’s Somnium . Literature helped spark curiosity as new scientific understandings were developing, he explained. “Science fiction alone did not inspire the scientific revolution, but the literature of the era did allow people to imagine different realities—in some cases, long before those realities actually became real,” Simon wrote.

Literature—even beyond pure science fiction—can help us imagine modes of living alongside new technologies. Don DeLillo’s work, notably White Noise , is freighted with the anxieties of the Cold War era . A more recent novel of his, Zero K , is laced with awe and longing about the capacity of science to ward off death. Works of climate fiction have attempted to reconcile enjoying life with living morally in a time of chaos and destruction, and many Silicon Valley novels throw the ethical shortcomings of dangerous inventions into relief. If art and technology have an invention feedback loop, perhaps they could develop an ethical one, too. Novels about technology tend to focus on the existence and the drama of dystopian tech itself—but they’re even more powerful when writers use narrative to examine the people that created those tools, and the human dynamics driving their existence. Writers have a unique power to explore moral questions about any new invention. Even more than new gadget ideas, the real world of tech could stand to learn from that.

Related:

Tags

Who is online

59 visitors

An article for Sci-Fi lovers who appear to be the sanest group on NT.

My reading suggestion in the genre is Michael Moorcock's The Dancers at the End of Time.

I read some sci-fi. My preference is time travel or alternate timelines. I recently acquired Robert Heinlein's "Stranger in a Strange Land" and will commence reading it this weekend...if Mr Giggles leaves me alone enough to read

I have this one too. I liked it a lot.

I have most of Moorcock's books including this one. I prefer The War Hound and the World's Pain myself.

I knew there was a reason to like you.

I'm also a big Roger Zelazny fan.

Be still my heart!

Love Moorcock, Heinlein, Zelazny. But James P. Hogan and Larry Niven have to be 2 of my favorites. A BIG BIG suggestion nowadays is Dennis E. Taylor's Bobiverse series.

I just finished reading Marko Kloos' Frontline series - It's 8 books long, but they read fast and are free on Kindle Unlimited if you are subscribed.

Of further interest is Sci-Phi: Science Fiction as Philosophy , a 24 part lecture series by David Kyle Johnson, Ph.D., University of Oklahoma.

I'll have to check that out.