Are Native American Dual Citizens of the US. The Indian Citizenship Act at 100 years old.

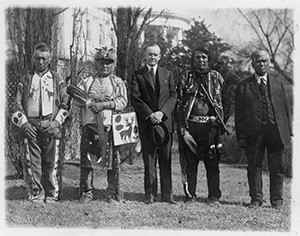

One hundred years ago President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act also known as the Snyder Act.

THE INDIAN CITIZENSHIP ACT AT 100 YEARS OLD

The Promise of Citizenship

President Calvin Coolidge and four Osage Indians, White House, 1925 ( https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/94508991/)

One hundred years ago, on June 2, 1924, the United States government conferred citizenship on Native American people by passing the Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act. Prior to that time, Native Americans had been explicitly denied citizenship—first in the United States Constitution and, later, through the 14 th Amendment. However, while the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 ensured that all Native Americans born within the United States had citizenship, the Act failed to fulfill the promise of citizenship because Native Americans were not also granted voting rights. It would be decades before all 50 states granted Native American citizens the right to vote. And even today, due to the inequities that Native Americans endure when accessing registration, early voting, and Election Day polling places, the promise of full citizenship remains broken.

While the 15 th Amendment declared that the right to vote could not be denied on account of race, many states were able to find other ways to deny Native American people the vote—residence on a reservation, tribal enrollment status, taxation, and incompetency were all used by states as reasons to disenfranchise Native people. One tragic outcome was that thousands of Native American veterans— including American Indian Code Talkers returning from World War II— found themselves prohibited from participating in basic civil liberties in the nation that they had risked their lives to protect.

In reality, Native voting rights often have come about only because of extensive advocacy and litigation by Native American individuals, organizations, and Tribal Nations. Native voters have had to fight (sometimes repeatedly) to have their voices heard. So, on this 100 th anniversary, we reflect on 100 years of Native American efforts to fully realize their citizenship and obtain equal access to their freedom to vote. We also honor 100 years of Native American citizens working tirelessly to make things better for future generations.

100 Years of Fighting for the Freedom to Vote

Native voters have had to fight for the enforcement of their civil rights since the moment that they were granted citizenship 100 years ago. To that end, since its founding in 1970, NARF has undertaken high-impact cases that will ensure equal and fair access to voting for Native American citizens. Repeatedly we have encountered voting rights abuses against Native Americans in Alaska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Arizona, New Mexico, and other states with significant Native American populations.

NARF’s legal work protecting Native voting rights is part of a long history of persistence across Indian Country to obtain and protect Native civil rights. Using the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and various sections of the Voting Rights Act, Native American voters have filed dozens of lawsuits to gain access to elections and to have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. A 2008 review of voting rights cases involving Native Americans and Alaska Natives as plaintiffs identified 74 cases, filed in 15 states. Tellingly, the Native plaintiffs won over 90% of cases- they lost only four of these cases, obtained partial success in two, and secured victories or successful settlements in the remaining 68 cases. That is an impressive record of success, often based upon dismal facts.

Elizabeth Peratrovich (Tlingit) advocated for the nation’s first anti-discriminatory laws, which passed in Alaska in 1945. Alaskans celebrate her activism on April 21, Elizabeth Peratrovich Day.

Why do Native people have to litigate for their right to vote? Because state governments repeatedly pass legislation to prevent Native American voter participation. State laws that directly restricted Native voter participation were on the books as recently as 1957. In more recent years, voting restrictions have expanded from direct denial of voting rights to the dilution of voting rights and indirect (but effective) impediments that capitalize on systemic inequities. Given their lack of representation, Native Americans continue to see gross disparities in services and infrastructure—things like transportation, broadband, and home addressing. These disparities can be exploited as barriers to registering to vote, voting, and having votes counted.

Today, 100 years after the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, Native people still are forced to litigate for their right to vote. Tragically, states continue passing legislation that prevents Native people from voting in federal and state elections. For example, in Montana, the state legislature passed the Montana Ballot Interference Prevention Act in 2018. The law restricted ballot collection, which is used heavily in isolated rural Native communities. The Assiniboine & Sioux Tribes of Fort Peck, Blackfeet Nation, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, Crow Tribe, and Fort Belknap Indian Community, Western Native Voice, and Montana Native Vote challenged the law in court. In 2020, the court ruled in the case, Western Native Voice v. Stapleton , that blocking ballot collection was unconstitutional and does not serve the state due to the detrimental impacts on Native voters. Incredibly, mere months after that ruling, the Montana state legislature again restricted ballot collection. Tribes and Native get-out-the-vote organizations in Montana were forced to return to court yet again to protect the rights of Native voters from anti-Native election-related laws. The court found again that the voting restrictions were unconstitutional. However, it begs the question: how many times should Native voters have to go to court to protect their freedom to vote?

Meanwhile, in 2022, the Spirit Lake Tribe, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, and several voters filed a lawsuit challenging North Dakota’s state legislative map as unlawfully diluting the voting rights of Native Americans. The U.S. District Court for North Dakota determined that the districts in question were not legal under the Voting Rights Act and ordered a legal and fair map to be adopted. Rather than working to adopt a legal map and ensuring that all voters in North Dakota could be heard, the state’s Attorney General poured more resources into appealing the decision and is advancing legal theories challenging the right of Native litigants to be able to bring cases under the Voting Rights Act at all. That case’s appeal, and the radical attempt to block private plaintiffs from accessing the Voting Rights Act’s protections, is still under consideration in the higher courts.

Obviously, these voting restrictions reflect persistent racism and bigotry, but there also is a pragmatic reason for disenfranchisement. A fully enfranchised Native electorate is powerful. In many parts of the United States, Native voters could change the outcome of elections. Native Americans are poised to sway local, state, and federal elections. They make up key voting blocks in states like Arizona, Alaska, Nevada, Montana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, to name a few. Voting restrictions that target these communities can greatly influence electoral outcomes.

Elvis Norquay (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa) challenged North Dakota’s voter ID laws that restricted access to voting based on a person’s housing status and having identification that included a postal address even though many homes on reservations in North Dakota had not been issued postal addresses.

Democracy is Native

Ironically, despite not having full access to enfranchisement and the privileges of citizenship, Native Americans have contributed greatly to this nation’s democratic fabric. In fact, Native American cultures heavily influenced the development of early American democracy. Well before the founding of the United States, even before the arrival of the earliest European explorers and colonists, some of the region’s Indigenous Peoples had federalist systems of government. When the delegates of the United States’ 1787 Constitutional Convention met, many of them were well-familiar with federalism-in-action through their contacts with Indigenous governments. Famously, Benjamin Franklin cited the structure and strength of the Iroquois Confederacy as an organization the colonies could emulate as they formed their new union.

Democracy is Native and NARF is committed to protecting it. The obstacles faced by Native voters are unreasonable and unfair and rob them of their collective political power. The fundamental promise of American democracy, of Native American democracy, is that everyone can participate and effectuate change. One hundred years ago, Native American were promised citizenship and all the benefits thereof. We fight every day in courts and congress across the United States to hold governments accountable and honor that promise.

LINK TO ARTICLE; https://narf.org/the-indian-citizenship-act-at-100-years-old/#:~:text=One%20hundred%20years%20ago%2C%20on,as%20the%20Indian%20Citizenship%20Act.

OFF-TOPIC COMMENTS WILL BE DELETED WITHOUT WARNING.

A question that most Americans are unaware of is the question of dual citizenship of Native Americans. Under the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 it is addressed and YES WE ARE DUAL CITIZENS.

First, we are citizens of our tribe and then Citizens of the United States of America.

For example, I am a citizen of the Ojibwe Nation and the United States thus a dual citizen since the US recognized the Ojibwe as an independent Nation.

My grandfathers and grandmothers on both sides were born in the 1870s/80s and were not US citizens until 1924 all four of them turned it down. Since one grandfather fought in the last battle of the Indian wars, Leech Lake MN, 1898 he felt that being a citizen of his tribe and nation was more than enough. Both my father and mother were born before 1924 so neither was a citizen until 1924.

It does get complicated since one grandparent was born in Canada and is a citizen of the Ojibwe Nation and both Canada and the US.

It is a unique situation but one that we (Native Americans) hold dear. Our Tribal Citizenship goes back thousands of years, and our US citizenship a short one hundred years.

I was told recently that (The very rights & existence you have today came from those very people you dislike so much.) by an NT member.

That comment is false on many levels.

So, yes I am a dual citizen of the United States of America.

But, being a dual citizen in the U. S. does not give us the same Constitutional rights as non-Natives - including Illegal Immigrants - the "so-called" Bill of Rights.

gullible people that vote for their oppressors usually get what they deserve...

ICRA is different from the Constitution's Bill of Rights.

ICRA’s guarantee of free exercise of religion does not stop a tribe from establishing a religion. Many tribes do not separate religion from government and other areas of life.

The ICRA guarantees a criminal defendant the right to a lawyer at the defendant’s own expense, BUT a tribe does not have to provide a lawyer for a defendant who cannot afford one.

There is no right to a jury trial in civil cases under the ICRA.

Yes, there are some differences between the two.

[✘]

Can you imagine...

What would have happened had the Europeans not brought disease with them?

Or that NT member's view about whites and Indian if there were still 120 million Indians

and probably not 50 states...

[✘]

I am not sure that I am striking the right tenor here, but here goes:

There are 'forever' forces arrayed against allowing such change to come. Cutting through the noise of centuries in the U.S. there are many, shall we call them, "originalists" that see the voting power of minorities (including women as a class) as seeking to compete with and top their power. That is, they choose to not give up any of their own capacity to minorities. . . for fear that a day will come (as promised) when minorities can band together and Kavika as you put it, "effectuate major change."

The article lists recent and current moves to limit our ability to vote, and although we were made citizens in 1924 it was not until the 1960s that all states followed suit and allowed us to vote.

It has been an ongoing battle for decades, CB.

I'm curious. . . are any so-called, 'blue-states' part of the opponents battling Native American voting rights? (I don't know, but would like to get a sense of scale on this.)

It's mostly red states, the most recent, North and South Dakota, Montana, OKlahoma etc.

I see. I will try to research the blue states that are part of the problem. The red states sadly are expected to oppose any sort of changes to control. Thank you.

A treat (for me anyway) :

Credit :

Sounds so much like the Blacks in that war who came back home to face the status quo of their prior condition and "station." Oh the highs and lows of being in the land of the free while yet maintaining a collective station.

My father was a recipient of that treatment after he came home from WWII.

This is a huge problem in the US/Canada/Central America.

MMIW, Murdered Missing Indigenous Women.

This is a real problem right now that the media doesn't really want to talk about. I know for a fact that our local media won't talk about women being abducted around the tourist area because it's bad for business.

Sadly, that is true, evilone. That and the response of law enforcement is for shit at best and that includes the FBI.

Kavika, this is not the information I went in search of, but it is very delightful read about this very thing with a positive outcome in a few key states. (I will continue to seek what I was after too.)