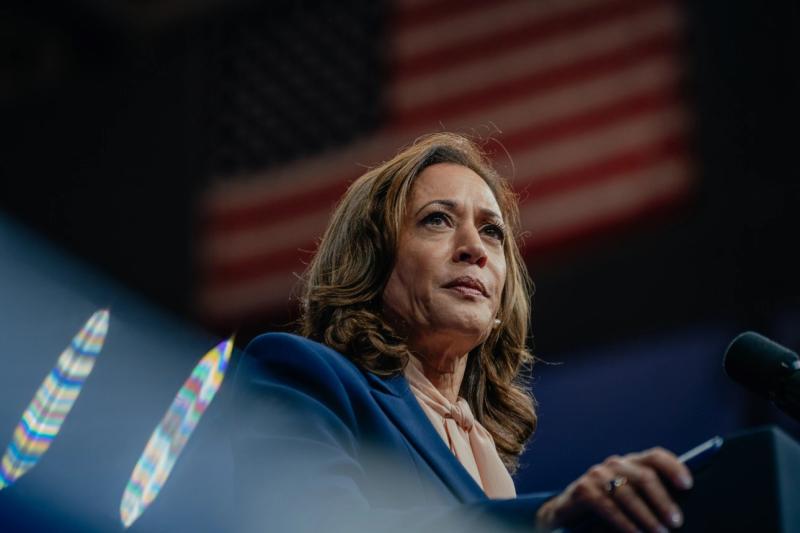

Kamala Harris is making one big strategic break from Hillary Clinton

Kamala Harris, if elected, would make history as the first woman president. And she’s letting that fact speak for itself.

Harris — already the first Black woman and South Asian American person to lead a major party ticket — is not, so far, heavily promoting the history-making elements of her campaign in TV ads or in her stump speech, focusing instead on her middle-class upbringing and prosecutorial track record. It’s a marked departure from Hillary Clinton, the first female Democratic presidential nominee, who highlighted her gender throughout her 2016 run, immortalized in white pantsuits, the Javits Center glass ceiling and the slogan: “I’m With Her.”

The vice president’s strategy reflects a candidate of a different generation and circumstance than Clinton, who lost to Harris’ now-opponent, Donald Trump, in 2016 and who will speak at the Democratic National Convention on Monday night.

“Quite frankly, talking about, ‘I’m the first Black this, I’m the first that,’ gets you nowhere,” said former Illinois Sen. Carol Moseley Braun, who ran in the 2004 Democratic presidential primary and was the first Black woman to serve in the Senate. “It really puts you in a corner and leaves you open to being accused of ‘playing the race card,’ and so she has not done that, and that’s very smart of her.”

Moseley Braun, who called for removing the metaphorical “men only” sign from the White House door during her own presidential run, said that Harris is “inheriting a different kind of playing field,” where “times have changed” and “people are more open to women doing these things.”

Harris, eschewing Clinton’s example, appears instead to be borrowing from Barack Obama, who, barring a few exceptions , did not talk much about his race in his own historic 2008 campaign. Even as Obama benefited from Black Americans’ enthusiasm for his candidacy, he spent most of his time speaking to a broader electorate, especially the white swing voters he needed to win battleground states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan.

Harris is taking a similar approach. Her TV ads in swing states talk up her work as an attorney general, a college summer job at McDonald’s, and her record of taking on Wall Street banks and Big Pharma, all while images flash on the screen of her alongside cops and workers wearing hard hats. In her biggest stretch of retail campaigning yet, Harris embarked on a bus tour this weekend across western Pennsylvania, a predominantly white area home to many union Democrats-turned-Trump supporters.

“She will have to bring in more of those voters who see themselves living on the outskirts of hope. They’re the voters that Trump picked up,” said Donna Brazile, a former Democratic National Committee chair who is part of a small group of women Harris turns to for advice. “Remember, Obama had them. He won Indiana. Now she has to get them. And the same way that Barack Obama appealed to them, you have to appeal to them based on values and they know that you care for them, that you see them.”

“There’s no other way to win in America,” said Brazile, the first Black woman to manage a presidential campaign.

Harris isn’t avoiding her identity, even if she is not making it a centerpiece of her campaign. Last week, she told new students at Howard University , her alma mater and a historically Black college, that one day “you might be running for president of the United States.” In an interview with Essence, she talked about growing up in a community where she was told as a child that she was “young, gifted and Black,” referencing a Nina Simone song and an Aretha Franklin album. Harris’ walk-on music features Beyonce’s song, “Freedom,” while her merch store sells T-shirts that read “The First But Not the Last.”

And in her time as vice president — before she replaced Biden at the top of the ticket — she showed an eagerness, at times, to speak with striking candor about her trailblazing career and obstacles facing people of color. This spring, while speaking at a health forum for Asian-American, Native-Hawaiian and Pacific Islander organizations, Harris gave them advice about breaking barriers and being first to do it.

“We have to know that sometimes people will open the door for you and leave it open,” Harris said. “Sometimes they won’t, and then you need to kick that fucking door down.”

Even so, Harris has largely limited such appeals to times when she is speaking directly to those communities, or when she’s trying to excite the Democratic base or raise money — appealing to the kinds of voters who would be motivated by voting for a “first” candidate. To the extent that gender features at the Democratic National Convention this week, it will largely be base voters Democrats are trying to excite.

Harris also doesn’t benefit from “Obama’s maleness and she doesn’t have Clinton’s whiteness,” said LaTosha Brown, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, a progressive voting rights group.

“She’s navigating a new space,” Brown said.

People who have known Harris for years said that the approach isn’t new for her, after having shattered barriers as district attorney, attorney general and senator. As a local and state candidate in California, she bristled at questions from reporters about her identity, seeing them as a distraction from her campaign’s focus on values.

“She always joked — people asked her, ‘What’s it like to be the first woman attorney general or DA?’ And she’s like, ‘I don’t know what to tell you, I’ve always been a woman, so I don’t really understand what it would be like to be somebody else,’” said a person who worked with Harris when she served as attorney general and was granted anonymity to speak frankly. “She’s like, ‘pretty unoriginal question, I don’t know what to do with that. I can tell you what I care about.’ She does try to approach this as: ‘My job is to tell voters what I’m about, what I care about.’”

Unlike Harris, her Republican opponent, Trump, has focused heavily on her identity in his efforts to demean Harris, the daughter of Jamaican and Indian immigrants. The former president has questioned her biracial identity , asserting that she only recently “became Black.” He regularly mispronounces her name and recently referred to her as a “beautiful woman” — a string of dog whistles, critics say, aimed at invoking racist and sexist stereotypes. Trump’s running mate, Sen. Sen. JD Vance , once referred to Democrats as “childless cat ladies.”

Harris’ responses to such attacks represent “a way different approach” from “gender politics [that] has been used in the past,” said Sen. Amy Klobuchar , who became the first woman to represent Minnesota in the Senate when she was elected in 2006.

“Instead of saying, ‘Oh no, that’s sexist,’ they said, ‘Really? This is hilariously weird,’” Klobuchar said, citing the Harris campaign’s response to Vance’s “childless cat lady” line. “They’ve picked moments to ignore it … but they’ve also [used] humor to take them on.”

One reason Harris may not highlight her gender is because she didn’t need to in a primary. In 2016, Democratic strategists said Clinton emphasized her gender, in part, because she faced a serious challenge from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) — and needed to differentiate herself from her husband, former president Bill Clinton. Spotlighting her history-making candidacy was an effort to excite the liberal base.

Harris, on the other hand, can run “the more Obama playbook,” where she’s saying, “we don’t have to talk about it — you can see I’m a woman of color,” said Patti Solis Doyle, who managed Clinton’s 2008 run, becoming the first Latina to manage a presidential campaign.

That decision, Solis Doyle said, “would not be possible if Hillary hadn’t leaned into it before her” because Clinton “got us to a place where it’s not front-and-center, and it’s not the first thing voters look at.”

Harris’ approach, as her mother would say, didn’t fall out of a coconut tree. It’s built on top of the strategies used by a wave of women who have run for office since 2016, many of whom also opted against centering the history-making nature of their bids.

During their 2022 race, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore and Lt. Gov. Aruna Miller also “did not talk about” how they’d be the first Black and South Asian statewide leaders of Maryland, Miller said.

“Look, anybody that was in the room looking at us could tell, we were a unique ticket,” Miller said. “There was no need to talk about it. It was more about our stories.”

The visibility of women and women of color in positions of power has also grown significantly since 2016. Women now represent 28 percent of members of Congress, compared to less than 20 percent of it in 2016. Twice as many women governors are in office in 2024 than in 2016, according to Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics .

“The face of power has changed,” said Rep. Lauren Underwood (D-Ill.), who was part of that wave of women elected in 2018, becoming the youngest and the first Black woman to represent her district. “In 2019, the most powerful voices coming out of Washington, D.C., were Nancy Pelosi and the Squad.”

But even in 2020, when six women ran for the Democratic presidential nomination, they were dogged by whispers about their “electability” against Trump. Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren sparred on the debate stage over whether the Vermont senator privately told Warren that a woman couldn’t beat Trump. At the time, Klobuchar called sexism “a real barrier” for the women running for president.

“Because of who Donald Trump is, because of the 2016 election, people thought that a woman couldn’t beat Trump,” Klobuchar said in a recent interview with POLITICO. “This time, as the polls show, in fact, they strongly do believe a woman can beat him.”

“That is a major, major, major shift, and, to me, this didn’t all happen at once,” Klobuchar added.

Indeed, public polls find Harris leaping ahead of Trump in some battleground states and national surveys. She’s built on an ever-widening gender gap for Democrats, where she holds a 10-percentage point edge among women compared to Trump’s 9-point lead among men, according to a CBS News poll released Sunday .

Even with that progress, women running for elected office still face hurdles not felt by their male counterparts. When making TV ads, for example, men “get to throw on the same blue shirt,” said Meredith Kelly, a Democratic ad-maker who worked on Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand’s 2020 presidential run, while “women have to wonder: is a dress too feminine? Is a suit trying too hard? Can we wear pink?”

“Women are judged on the words they say and how they say them. And while men are seen as strong if they attack their opponents, women can be considered whiney or rude if they do the same,” Kelly said. “Female candidates and their teams have to think about each and every move through a different lens than men do.”

Kelly added, “We have made a lot of progress … but this is still an ongoing project.”

Democrats hope the fact that Harris already served as vice president for the past three-and-a-half years means that Americans have become accustomed to the image of a woman in the White House. And Clinton already broke the barrier of becoming the first woman Democratic presidential nominee, so that’s not new, either.

There are “many, many, many, many more women [in elected office] at all levels, and it just wasn’t necessarily like that in 2016,” Underwood said. “There’s been this huge increase in the number of women in power, both in elected office and grassroots, community organizing, and I think that Kamala Harris is really benefiting because we’re ready,” Underwood said. “We saw, and we got in formation.”

Women now make the rules and have reserved the right to change them as soon as men learn them ... it's a good thing.