How “Useless” Science Unraveled an Amphibian Apocalypse

O ne spring day in 1984, Joyce Longcore got a phone call from Joan Brooks, a biologist at the University of Maine. Brooks had received a National Science Foundation grant to study the interactions of fungi and bacteria in peat bogs. She needed a hand, and she heard through the grapevine that Longcore knew a bit about fungi.

Longcore did. She’d studied them at the University of Michigan in the late 1960s before leaving lab life to raise a family full time. Now her oldest son was headed to college and she was looking for something to do. She’d figured on getting a job at the grocery store. Instead she took Brooks up on the offer. When their work ended after several years—it would later inspire a commercial peat-based sewage filtration system —Longcore decided to get her doctorate. The focus of her research: a division of fungi called chytridiomycota, or chytrids.

At the time, chytrids were about as obscure as a topic in science can be. Though fungi compose an entire organismal kingdom, on a level with plants or animals, mycology was and largely still is an esoteric field. Plant biologists are practically primetime television stars compared to mycologists. Only a handful of people had even heard of chytrids, and fewer still studied them. There was no inkling back then of the great significance they would later hold.

Almost overnight Longcore went from obscurity to the scientific center of an amphibian apocalypse.

Longcore happened to know about chytrids because her mentor at the University of Michigan, the great mycologist Fred Sparrow, had studied them. Much yet remained to be learned—just in the course of her doctoral studies, Longcore identified three new species and a new genus—and to someone with a voracious interest in nature, chytrids were appealing. Their evolutionary origins date back 600 million years; though predominantly aquatic, they can be found in just about every moist ure-rich environment; their spores propel themselves through water with flagella closely resembling the tails of sperm. Never mind that studying chytrids was, to use Joyce’s own word, “useless,” at least by the usual standards of utility. Chytrids were interesting .

The university gave Joyce an office and a microscope. She went to work: collecting chytrids from ponds and bogs and soils, teaching herself to grow them in cultures, describing them in painstaking detail, mapping their evolutionary trees. She published regularly in mycological journals, adding crumbs to the vast storehouse of human knowledge: “ Morphology and Zoospore Ultrastructure of Chytriomyces angularis sp. nov . (Chytridiales) ,” “Zoospore ultrastructure of Monoblepharis polymorpha, ” “Chytridiomycete taxonomy since 1960.” The last established that blastocladiales, then recognized as an order within chytrids, is a phylum unto itself, which was a bit like realizing that sea slugs and monkeys don’t belong in the same category—though, mycology being what it is, only a few devotees would notice. A particularly big crumb, then.

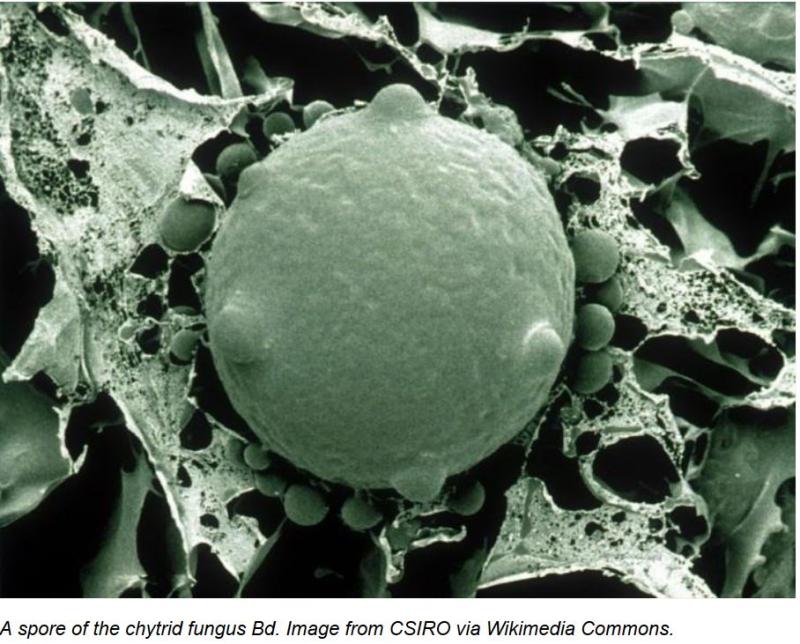

And so it might have continued but for a strange happening at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., where poison blue dart frogs started dying for no evident reason. The zoo’s pathologists, Don Nichol and Allan Pessier, were baffled. They also happened to notice something odd growing on the dead frogs. A fungus, they suspected, probably aquatic in origin, though not one they recognized. An internet search turned up Longcore as someone who might have some ideas. They sent her a sample which she promptly cultured and characterized as a new genus and species of chytrid : Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, she named it, or Bd for short.

Article is LOCKED by moderator [smarty_function_ntUser_get_name: user_id or profile_id parameter required]

Article is LOCKED by moderator [smarty_function_ntUser_get_name: user_id or profile_id parameter required]

Which is why I'll always support scientific research of any kind, even if the knowledge is considered useless for years, decades, centuries there will come a day when it is important.

One never knows what the study of ''useless'' will result in...

We should always encourage scientific research.

It's only ''useless'' until it isn't.

...another piece of the vast puzzle.

We see them all the time: the mocking headlines about research into the nuptial dance of komodo dragons, or somesuch. "What a waste of money!"

Fascinating post, SP.