In Ahmaud Arbery Shooting, a George Zimmerman-Style Defense May Resonate With Georgia Jurors

By: Roger Parloff (Newsweek)

Gregory and Travis McMichael, the father and son charged in the shooting death of Ahmaud Marquez Arbery, appear likely to invoke a defense similar to that raised by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman when he won acquittal of second-degree murder and manslaughter charges in the 2012 shooting death of Trayvon Martin, the unarmed 17-year-old African-American who was shot to death while visiting his father in Sanford, Florida.

Arbery, an unarmed, 25-year-old black man, was killed in February near Brunswick, Georgia, after a scuffle with Travis McMichael, 34, who was armed with a shotgun. Travis and Gregory, 64, who was carrying a .357 magnum, suspected Arbery of having committed burglaries in the area, Gregory has said.

Like the McMichaels, Zimmerman was not arrested immediately after the shooting. He was charged only after six weeks of mounting public outrage and media pressure. At trial, the defense maintained that when Zimmerman stopped Martin, Martin attacked him, had him on the ground and was hammering his head into the ground. Fearing for his life, Zimmerman shot him, according to the defense. Zimmerman did have head lacerations and some neighbors saw a fight and heard yells for help. The jury acquitted Zimmerman after two days of deliberations.

In addition to the Zimmerman example, the McMichaels have a surprising source for material for their defense—the three-page memo written last month by an early prosecutor in the case, Waycross District Attorney George Barnhill, who found no probable cause to arrest the pair.

"Given the fact Arbery initiated the fight," wrote Barnhill then, "at the point Arbery grabbed the [suspect Travis McMichael's] shotgun, under Georgia Law McMichael was allowed to use deadly force to protect himself."

In an email response to questions from Newsweek, Barnhill declined to discuss the Arbery case specifically because of ethics rules. But he wrote, "In general terms, I think it's an excellent idea to research and write about Georgia's unique laws on citizen's arrest, rights of public carry of firearms, and self-defense. What 99 percent of America think they know about these laws comes from TV and movies which are generally and loosely based on California and New York, not Georgia."

Barnhill's exoneration of Gregory and Travis McMichaels appears to have held sway from Feb. 23, the day of the shooting, until about May 5, the day a cellphone video of the shooting was posted on the Internet by a local radio station. Within 36 hours, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) arrested the McMichaels, charging them with murder and aggravated assault. The U.S. Department of Justice has also said it is reviewing the incident to see if federal hate or civil rights crimes were committed.

GBI Director Vic Reynolds effectively repudiated Barnhill's analysis, saying "there was more than sufficient probable cause" to arrest the McMichaels. The GBI has said it is now scrutinizing Barnhill's handling of the case. The record of his office in two previous cases—involving controversial prosecutions of black women—has also aroused press scrutiny, and there have been calls for him to resign.

In his email to Newsweek, District Attorney Barnhill said: "As far as any investigation or review into my office, I welcome the review and look forward to working with them."

Though some controversy now swirls around Barnhill, as a prosecutor with 36 years experience practicing in both Brunswick and neighboring Waycross, his analysis provides considerable insight into the likely defense—and possibly into local juror perspectives. It also suggests that the case might raise inflammatory evidentiary issues over whether Arbery's criminal record can be introduced before the jury.

Lawyers for the McMichaels, who are still in custody, have characterized Arbery's death as a tragedy while denying that their clients are criminally responsible. "So often the public accepts a narrative driven by an incomplete set of facts, one that vilifies a good person, based on a rush to judgment, which has happened in this case," Gregory McMichael's lawyer, Laura Hogan, said last week. She and her law partner and husband, Franklin Hogan, have said that important additional evidence will be coming to light including—intriguingly—another video of the shooting. (Some such evidence might emerge at an as-yet-unscheduled preliminary hearing.)

"Travis has a presumption of innocence," said Travis McMichael's attorney Jason Sheffield at another press conference last week. "That presumption of innocence follows him from now throughout the course of this trial."

Before attempting a legal analysis of Arbery's case, it's helpful to recap what's known about the evidence so far, and how we got to this point.

Arbery was killed in the suburban Satilla Shores neighborhood near Brunswick, a coastal town about an hour north of Jacksonville, Florida. According to his family, he often jogged in that neighborhood and was jogging the day he was gunned down.

The McMichaels lived on Satilla Drive. Two doors down from them was a house construction site. The open site was owned by Larry English, who lived in Douglas, about 90 miles to the west. It was equipped with two motion-detector video surveillance cameras. Whenever the camera was triggered, it would send a text alert to English, who would notify the Glynn County Police Department, English's lawyer has said.

Between Oct. 25 and Feb. 23, the day of the shooting, the camera was triggered five times by a young black man who looks like Arbery. (Arbery's family has confirmed Arbery's identity only in the last clip, on the day of the shooting.) In the surveillance videos, obtained by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the young man is always dressed in shorts and running shoes, and on one occasion he can be seen leaving the site at a jogger's pace. Often, but not always, he came after nightfall. English's lawyer has said that nothing was ever stolen from the site. She has speculated that the young man might have been drinking water from the functioning faucets at the site. (On one occasion, last November, a white couple triggered the surveillance camera, also at night.)

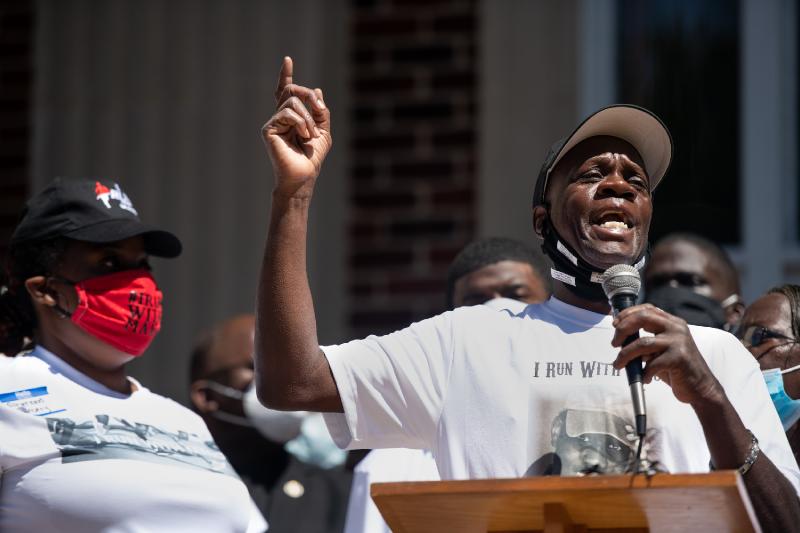

Gregory McMichael poses for a mugshot photo after being arrested in connection with the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, at the Glynn County Detention Center on May 7, 2020 in Brunswick, GeorgiaGlynn County Sheriff's Office/Getty

In mid-November, after the young black man had visited the site twice, surveillance video and descriptions of him were distributed on the neighborhood's Facebook page and Nextdoor app, according to the Journal-Constitution.

On December 20, three days after a young man had triggered the surveillance camera a third time, a Glynn County police officer texted English advising him that whenever he got an alert from his camera, "day or night," he should contact Gregory McMichael, who lived near the site and had a law enforcement background. Gregory had been an officer with the Glynn County Police Department from 1982-89, and then served as an investigator with the Brunswick D.A.'s office until he retired in 2019. English's lawyer told the Journal-Constitution that he did not notice this text until after the shooting, and that he never contacted McMichael, whom he doesn't know.

On January 1, 2020, an event occurred that may have nothing to do with Arbery—there is no evidence that links him to it—but which the McMichaels seem to have suspected did. Travis McMichael's pistol was stolen from his unlocked pickup truck, according to a police report. His truck had been parked outside the McMichael home, two doors down from the construction site.

At about 7pm on February 11, around the time the surveillance camera was next triggered, Travis McMichael made a 9-1-1 call (also obtained by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution). In it, Travis reported a black male having just entered the construction site.

"When I saw him and backed up, he reached into his pocket and ran into the house," Travis told the operator. "I don't know if he was armed or not but he looked like he was acting like he was." He said the man had "a flashlight looking through the house." He added, "we've been having a lot of burglaries and break-ins around here." (There has been no corroboration of actual burglaries. Visits to an open construction site would be misdemeanor trespasses, according to Ronald Carlson, a law professor emeritus at the University of Georgia. The taking of Travis' gun would be a felony theft.)

Finally, on February 23—the day of the shooting—the surveillance camera was triggered again, at about 1pm. Greg McMichael was in his front yard, according to the statement he would later give police. He saw a young black man "hauling ass" down Satilla Drive and believed that he recognized him as the same one involved in the earlier incidents. He went inside to get his son Travis, and then each armed themselves. They did so because of their suspicion—from the Feb. 11 incident—that he might be armed, according to the statement.

The McMichaels followed Arbery in their truck, Greg told the police. Travis, driving, tried to cut Arbery off, but Arbery turned and ran in the opposite direction, according to Gregory's account.

At that point, a man named William "Roddie" Bryan got involved, although it is not clear exactly how or why. Bryan's lawyer has said he did not coordinate with the McMichaels, though lawyers for the Arbery family have alleged that he did. Bryan also tried to block Arbery with his car, but failed, according to Gregory McMichael's statement.

At that point, Bryan, from his car, made the now ubiquitous cellphone video. Bryan is following Arbery as he runs at a jogger's pace down the street. Arbery is approaching the McMichaels' pickup truck, parked at the right side of the road. Greg is in the bed of the truck, while Travis is standing to the left of the driver's side door, holding a shotgun. According to the New York Times, Greg McMichael is actually making a 9-1-1 call from the bed of the truck at the time, describing a black male running down the street. (A remarkable detail, first revealed by the Times, is that Bryan's tape was leaked to the local radio station by an early attorney for the McMichaels, Alan Tucker. Evidently the McMichaels and Tucker regarded it as helping their case.)

As Arbery nears the truck, he veers to the right and goes around the right side of the truck, briefly out of view. Some yelling can be heard. The first shot rings out as Arbery, now on the far side of the truck, can be seen pushing Travis across the street toward the left, holding the barrel of Travis's gun, as the two scuffle. The two go off screen to the left, and a second shot is heard. They come back on screen, still scuffling, and there is a third shot. Then Arbery begins to stagger down the street, falling to the roadway a few steps later.

Here is Greg McMichael's account to the police, as recorded in the police report: "McMichael stated they saw the unidentified male and shouted 'stop, stop, we want to talk to you.' McMichael stated they pulled up beside the male and shouted stop again at which time Travis exited the truck with the shotgun. McMichael stated the unidentified male began to violently attack Travis and the two men then started fighting over the shotgun at which point Travis fired a shot and then a second later there was a second shot." After Arbery fell, Greg said he rolled Arbery's body over to see if he was armed, and discovered he wasn't.

The autopsy report showed that Arbery had three shotgun wounds—two "gaping" wounds to the chest, and one "deep, gaping, shotgun graze wound" to the right wrist.

Although the Brunswick District Attorney, Jackie Johnson, would have ordinarily handled the case, she deferred, because McMichael had worked as an investigator for her office. She therefore had the Glynn County police take the case to District Attorney Barnhill in Waycross, in the adjoining judicial district to the west. The next morning, Barnhill told the Glynn police that it looked to him to be a justifiable homicide, though he continued to hold the case while awaiting the autopsy report.

At some point Barnhill became aware that his son, who worked in the Brunswick D.A.'s office, had handled a "felony probation revocation" involving Arbery, and had also actually worked with Gregory McMichael on a "prosecution of Arbery," according to the New York Times.

Barnhill nevertheless kept the case until Arbery's family began alleging that he suffered from a conflict of interest. On April 3, a few days after the autopsy was completed, Barnhill wrote to a Glynn police captain, explaining that while he thought the conflict allegations were meritless, he would ask the Georgia Attorney General's Office to appoint a new prosecutor. He went on to provide his detailed explanation of why he had concluded there was "insufficient probable cause to issue arrest warrants."

(On April 13, the Georgia Attorney General's Office appointed the third district attorney to the case, replacing Barnhill. But on May 11, after the video emerged, the Attorney General transferred the case to a fourth district attorney, Joyette Holmes of Cobb County, north of Atlanta, citing the greater resources in her office. Holmes is the first African-American to hold the office.)

In finding no grounds to arrest the McMichaels, District Attorney Barnhill focused first on Georgia's citizen's arrest law. That law allows a private person to make an arrest in two circumstances. First, "if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge." Alternatively, he or she can make an arrest "upon reasonable and probable grounds for suspicion," but only "if the offense is a felony and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape."

In his letter, Barnhill calls Arbery "a burglary suspect"; says the McMichaels were acting with "solid, first-hand probable cause"; and says that they were "asking/telling him to stop."

"It appears their intent was to stop and hold this suspect until law enforcement arrived," Barnhill wrote. The fact that the McMichaels were armed was lawful under Georgia's "open carry" laws, he added.

Carlson, the University of Georgia law professor emeritus, says the citizen's arrest claim may be an "uphill battle." Carlson isn't sure the provision would apply, based on what we know so far. The only offense committed in the McMichaels' presence appears to be Arbery's unauthorized presence on the open construction site—a misdemeanor trespass. Nobody saw Arbery steal Travis's gun, and any evidence that he did so is highly circumstantial. There's no evidence at all that Arbery committed any actual burglary.

In his April memo to the police captain, Barnhill concludes that Arbery attacked Travis McMichael and that Travis responded in self defense. Relying on the cellphone video that Roddie Bryan made, Barnhill writes: "It appears that Ahmaud Arbery was running along the right side of the McMichael truck then abruptly turns 90 degrees to the left and attacks Travis McMichael, who was standing at the front left corner of the truck. A brief skirmish ensues in which it appears Arbery strikes McMichael and appears to grab the shotgun and pull it from McMichael. . . . Given the fact Arbery initiated the fight, at the point Arbery grabbed the shotgun, under Georgia Law, McMichael was allowed to use deadly force to protect himself."

While that appears to be a fair reading of a section of the video, it leaves open the question of how and why Arbery came to be running along the right side of the truck in the first place. "The McMichaels set up that situation," says Carlson, the law professor—or at least that is how the prosecution will likely portray it. Travis, holding a shotgun, was blocking Arbery's path as he jogged on the street, while Greg was in the bed of the truck. Under these circumstances, "Arbery was not the aggressor," the prosecution will argue, Carlson says. "The law of self-defense cannot be invoked where the aggressor pulls the trigger." (Carlson is the author of 18 books on evidence, trial practice and criminal procedure.)

But Lawrence Zimmerman, president of the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (and no relation to George Zimmerman), is less willing to dismiss Barnhill's argument at this point, given how little we know so far. If the McMichaels were just asking Arbery to stop and talk, Arbery could still be seen as the aggressor—regardless of whether there were technical grounds for them to perform a citizen's arrest. "It could be they went to talk to him, drove up, guns pointed down," Zimmerman says.

In his analysis, Barnhill also cited in passing the state's stand-your-ground law—a law that became controversial in the Trayvon Martin case in Florida. (Contrary to pretrial speculation, Zimmerman's defense team did not ultimately invoke Florida's stand-your-ground law at his trial.) Barnhill didn't spell out what he had in mind, but it appears to relate to the fact that Travis McMichael had no duty to retreat when Arbery came towards him. "In some states, a person with a weapon has to retreat 'to the wall' before he can resort to using lethal force," Carlson says. Georgia is one of the more than twenty stand-your-ground states, however, he says. "If a person fears for his life, he's allowed to use a forceful response."

Barnhill raised one additional defense in his letter—a surprising one. "While we know McMichael had his finger on the trigger," Barnhill writes, "we do not know who caused the firings." What he means is that the gun may have gone off not because McMichael pulled the trigger, but rather because Arbery was pulling the barrel during the scuffle. "Arbery would only [have] had to pull the shotgun approximately 1/16th to 1/8th of one inch to fire [the] weapon himself and in the height of an altercation this is entirely possible."

That might be a more plausible argument had there been only one shot. Three well-spaced shotgun blasts may be harder to portray as accidental.

Finally, Barnhill, after raising the accidental shooting argument, raised a knotty evidentiary question. "Arbery's mental health records & prior convictions help explain his apparent aggressive nature and his possible thought pattern to attack an armed man," he wrote.

No one knows yet what Barnhill meant by "mental health records," but some references to Arbery's brief criminal history have emerged, from newspaper archives or from Barnhill's email to the attorney general April 7, alluding to the conflict-of-interest issues Arbery's family had raised against him.

In late 2013, when Arbery was 19, he allegedly tried to bring a loaded Big Bear .380 handgun into a high school basketball game. When officers tried to stop him, he fled and, though he was apprehended, a school officer fractured his hand in a fall. Arbery was indicted for that event in January 2015 and charged with two gun counts and three counts of obstructing an officer, according to the Brunswick News and a Jacksonville TV station. It's not clear how the case was resolved. In 2018, he was convicted of shoplifting and probation violation, according to the New York Times. (Emails and calls to three attorneys for Arbery's family were not returned.)

Could any of Arbery's criminal record be admitted before the jury? Professor Carlson, defense lawyer Zimmerman, and a second law professor, Russell Covey of Georgia State University, all say Arbery's record would most likely be found to be irrelevant, since the McMichaels themselves didn't know of the victim's history at the time of the incident. Georgia's evidentiary law was changed in 2013, according to Zimmerman, to make it harder to introduce character evidence of this kind.

Nevertheless, Carlson believes prosecutors will have to be careful not to inadvertently open the door to allowing that evidence in, by somehow implying that Arbery was law abiding or non-aggressive by nature. "I expect a real court dogfight on this issue because admission of the prior misdeeds will damage the prosecution," Carlson says.

In the days ahead, the McMichaels are expected to ask for a preliminary hearing. There, the prosecutor will have to present evidence to establish probable cause, and the McMichaels will have a chance to present some, too, if they choose.

But just as important as the facts is the jury pool that will sift through them. That D.A. Barnhill saw no need to make any arrests, and that the McMichaels themselves thought Bryan's cell phone video was helpful to them, may signal that many local jurors' perspectives may not align with the public whose outrage ultimately prompted the charges.

So much wrong here.

That it went through four DA's...

Sorry but it is a stupid law that anyone can hold someone at gunpoint just for what they think is suspicion.

I am guilty myself as over the years I have stopped at looked at houses under construction.

No matter what they say, they were aggressors and tracked and followed the young man, even blocking him with their vehicles.

That right there is what makes me suspicious of the white guys. And who steals stuff at 1 o'clock in the afternoon...broad daylight?

They could also see he was not carrying anything. Plus the owner of the home under construction never had anything stolen.

Like I said above, I have gone in and looked at houses under construction. Looking at the layout and how it was being done.

I guess I am a criminal now.

I couldn't see anything in his hands in that poorly shot video

I have seen, (I think), all the related videos. The actual shooting itself was disturbing, (most news agencies cut away at the end, where the kid tries to run away only to collapse after a few feet and dies on the street, with his killers watching). This kid had stopped at the under construction house on several occasions, apparently to access a water source, (a spigot in the front or back of the house), to get something to drink and splash water on his face while jogging. I have wandered through house constructions myself more than once, and fairly recently. At worst, it's trespassing, which would probably garner a warning and a, "please don't do it again", at worst. In none of the videos is the kid seen taking anything and the owner confirmed that nothing was missing. In the video where he is shot, I saw some on the right, on Twitter saying that he attacked the guys that were armed. I highly doubt it. The kid was unarmed, and picking a fight with two people with shotguns seems VERY unlikely. I think it's far more likely that once the shooting started, Ahmaud did what most people would do, fight for his life and went after the person that wasn't in the truck. I know that's what I would have done.

Arbery was at a disadvantage in this entire scene. He was perused and ultimately shot and killed. Trying to remain as unbiased as I can, I can only come to one conclusion; Aebery was murdered, no more, no less.

Even if Arbery HAD stolen something, that is still NO justification for execution even if he did have his due process.

I agree with Prof. Carlson's take. Two grounds for making a citizen's arrest: 1) crime has to be committed in your presence or immediate knowledge, and the Georgia Court has held the terms are synonymous. No crime allegedly committed. Even if there was, there is an element of immediacy. Can't be talking about something that happened a month ago. So 1 is out. 2) if the crime is a felony and the offender is apparently fleeing. Again, there is no crime claimed. The McMichaels originally claimed they thought he might be the person targeting the area for burglary...at some unknown point in time. More info has come out, but nothing I would say gives them any ground to make a citizens arrest.

Self-Defense? You can't be the aggressor. Chasing a guy down the road, with guns, makes you the aggressor, and would put the guy being chased in immediate fear of death or severe bodily injury.

Here are the pertinent portions of 16-3-2, ie self defense.

If you can't make a lawful citizens arrest, you are the aggressor. I'm not even going to touch subsection (b)(1). Who knows what the intent was?

Why even bring up stand your ground?

I can't see that the use of force was in accordance with the code section. This isn't Tombstone. Call the damn police.

Well, never mind, maybe don't call the police. Apparently the cops already told them to employ the local vigilantes. "Uh, hey, look, we don't want to get involved. If this happens again, call one of your neighbors, he has a background in law enforcement. But, don't call us."

Supposedly McMichael was making a 911 call while driving down the road. I'd like to hear the contents of that conversation.

Exactly. Some were claiming that Arbrey was armed. In the video, you can see him running down the street in a t-shirt and shorts. If he was armed, I didn't see it nor did I see where he could have hidden it, (not saying it's impossible, just pointing out that it's unlikely). Also, if he was armed, why would he resort to fighting with his fists at a close range? Why not stay at a distance and shoot from a semi-concealed position. I mean, that's common sense.

Give Arbery gun. Doesn't change anything for me. Rednecks in one truck that are attempting to stop you and are chasing you down the road. Another redneck following and filming from behind.

You can't be the aggressor. The other guy can't announce his intent to leave the fray. They approached, chased, and cornered him, and he was running away, or attempting to.

How stupid was it for the guy to film it to begin with, essentially proving that Deputy Dog and his son intentionally murdered Mr. Arbery.

I'm glad they did.

Me too.

Just want to clarify to some readers, we are glad it was taped, not for the murder.

Absolutely. Although, I would hope that much is abundantly clear.

Yeah I know but you never know. Haha

The trial will be a modern day version of To Kill A Mockingbird.