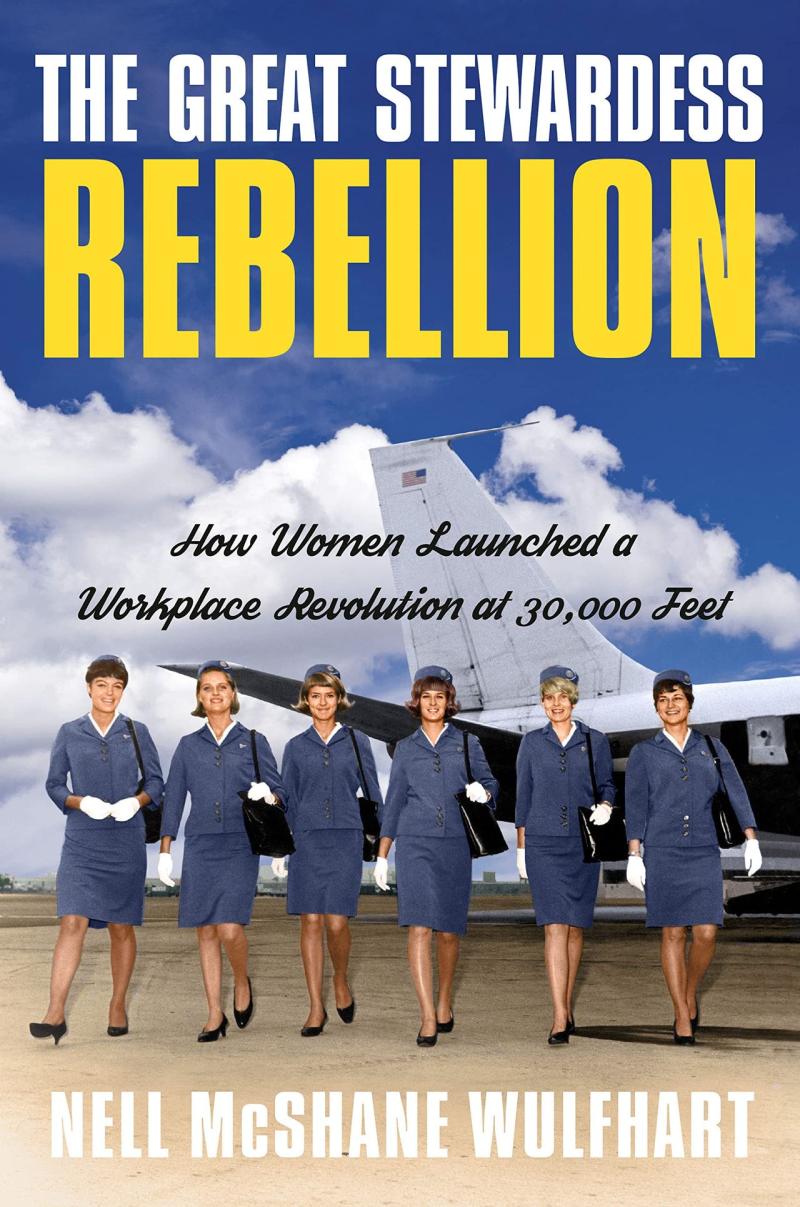

'The Great Stewardess Rebellion' Review: Revolution in the Sky

By: Barbara Spindel (WSJ)

Flight attendants in the 1960s were, to a one, young, thin, single women. But did they have to be in order to do the job? When stewardesses, as they were then called, began appealing to the newly created Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to challenge the airlines' discriminatory hiring practices, the airlines fought back, using what was known as the BFOQ loophole in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. They defended their right to hire only women and to fire them if they gained weight, married, got pregnant or entered their 30s, arguing that being a young, thin, single woman was, in fact, a "bona fide occupational qualification" for the position.

"It wouldn't be much of an exaggeration to say that in the 1960s the airplane cabin was the most sexist workplace in America," writes Nell McShane Wulfhart in "The Great Stewardess Rebellion." Most passengers at midcentury were male business travelers; airlines believed that having young, pretty stewardesses gave them a competitive advantage. Ms. Wulfhart's exhilarating account describes how a number of stewardesses, galvanized by the women's movement, took on the airlines and won.

Ms. Wulfhart, a journalist and the author of the audiobook “Off Menu,” centers her narrative around Patt Gibbs and Tommie Hutto, American Airlines stewardesses who became leaders in their union. Ms. Gibbs entered the American Airlines Stewardess College in Dallas in 1962 at age 19, beginning the six-week training program after signing a contract acknowledging that her employment was contingent upon her remaining attractive, pleasant and unmarried—and agreeing she would leave the job upon turning 32.

At the Stewardess College, nicknamed “the charm farm,” the women learned about food-and-drinks service and emergency procedures but were also instructed in standardizing their hairstyles, makeup and nails. Slowly, the trainees began to resemble one another. (The fact that they were all white was not spelled out like the other requirements but was implicit; American didn’t hire its first black stewardess until 1963.) “There was a saying among stewardesses,” Ms. Wulfhart notes, “that a pilot gained his identity when he put his uniform on, and a stewardess lost hers.”

The intense Ms. Gibbs was quickly drawn into the union. The stewardesses were represented by the air-transport division of the massive Transport Workers Union. Unlike Ms. Gibbs and Ms. Hutto, most stewardesses were uninterested in organizing: the age and marriage rules meant they wouldn’t be on the job for long, so why bother? Meanwhile, the union’s men—bus drivers, subway conductors, baggage handlers and maintenance workers—never failed to remind the women that they had families to feed. Ms. Gibbs came to feel that at every turn, in Ms. Wulfhart’s words, “the flight attendants were dominated by men, both American’s management and the TWU.

The passage of 1964’s Civil Rights Act opened legal avenues for the stewardesses. Their primary grievances were with the marriage and age rules, along with the humiliating weight checks. “The scale was weaponized,” Ms. Wulfhart writes, with management scheduling frequent public weigh-ins for those stewardesses perceived to be troublemakers.

As the women’s liberation movement exploded in the late 1960s, some stewardesses took to protesting. The airlines’ marketing frequently sexualized the flight attendants. (Several egregious ads are reproduced in the book.) In 1971 stewardesses joined members of the National Organization for Women in picketing the offices of the advertising agency behind National Airlines’ infamous “Fly Me” campaign, which featured real-life stewardess Cheryl Fioravante staring provocatively into the camera under the headline “I’m Cheryl. Fly me.” The picketers’ signs read “Go Fly Yourself.” The following year, hundreds, Ms. Hutto among them, joined Stewardesses for Women’s Rights, an activist group that found a loyal supporter in Gloria Steinem.

Through contract negotiations and lawsuits, the stewardesses gradually made progress. The eventual elimination of the age and marriage rules offered the possibility of a career instead of a brief stint between school and marriage. In 1971, after Celio Diaz, a man denied a job as a steward, sued Pan Am for sex discrimination and won, men began to enter the ranks. The women used the men as leverage to negotiate changes to their contracts. If men could do the job in flat shoes, for instance, why must women wear three-inch heels? When their new male counterparts got single rooms—stewardesses were still expected to double up—the women at American angered both the airline and the union by voting down the contract twice, insisting that it address the rooming issue. American finally caved.

Ms. Wulfhart is not the only author in recent years to rehabilitate the reputation of the unfairly maligned stewardess in the cultural imagination. Ms. Steinem’s 2015 memoir, “My Life on the Road,” credits flight attendants with fighting sexism and harassment on the job; Julia Cooke’s “Come Fly the World,” published last year, highlights the pivotal role of Pan Am stewardesses in Operation Babylift, the mass evacuation of orphans from Saigon at the close of the Vietnam War. Much of the ground in “The Great Stewardess Rebellion” has been covered before, most notably in Kathleen Barry’s 2007 “Femininity in Flight.” But Ms. Wulfhart is a vivid storyteller who writes with energy and style, and the experiences of Patt and Tommie, passionately pushing both the airline and the union to catch up with the changing times, lend her account poignancy.

A million applicants competed for 10,000 stewardess positions in 1965, Ms. Wulfhart reports. Of course, commercial air travel no longer projects the glamour that drew young women to these jobs in droves. The 21st-century travel experience means long security lines, delays, shrinking legroom and the occasional unruly passenger. Flight attendants surely still suffer their share of indignities at 30,000 feet—but these days we all do.

Ms. Spindel’s book reviews appear in the Christian Science Monitor, the San Francisco Chronicle and elsewhere.

For what it's worth: There are occupations in which appearances matter. Somehow that got lost in the shuffle.

The book is:

The Great Stewardess Rebellion: How Women Launched a Workplace Revolution at 30,000 Feet

Remember "coffee, tea...or me"

No, but I like it!

I dont fly often, but when I do I pay no attention to what the "stewardesses" look like. Their job is to help and serve the passengers , particularly should there be an emergency, not be eye candy.