Gratitude

The Lenten Season, those weeks leading up to the Passion and Resurrection of Christ, is as good a time as any for Christians to remind themselves of one thing that is all too easily forgotten:

The world is a gift.

The world can hardly be anything else from a Christian perspective. After all, Christians maintain that the world (the universe or cosmos) is a creature, the handiwork of a Creator. Unlike the pagans of antiquity, who regarded the world as either a brute fact, perhaps an emanation of an impersonal Being, Christians view it as the creation of a personal God.

Moreover, from the Christian vantage point, the world was created by God ex nihilo, i.e. not from some preexistent primal matter, as some of the pagans thought, but from nothingness. God created the heavens and the Earth, as Genesis informs us, and then declared His work good.

Being, or existence, is good. As St. Anselm of Canterbury put it in his (“ontological”) argument for God’s existence, “existence is greater than non-existence.” It is the most fundamental of all goods, for all others—virtue, intelligence, friendship, union with God, etc.—presuppose being. In order to enjoy anything, one must first exist.

Now, God created the world, not from any need or want on His part—the Supreme Being, given His perfection, can’t have needs or wants—but because God is Love and Love, from its very nature, gives of itself.

The world, then, is a gift.

And since the world is a gift, this makes its Creator, Sustainer, and Redeemer the Supreme Giver.

Human beings are in turn receivers.

Given this Giver/receiver relationship between human beings and the very Ground of all reality, the key to unlocking the secret of all secrets regarding the cosmos and, hence, living the human life that we are meant to live is nothing more or less than…gratitude.

The sole ingredient to aligning our lives with ultimate reality and flourishing as best that conditions in this fallen, temporal world permit is the oft-neglected virtue of gratitude.

The 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, a man who is unanimously (and rightly) regarded as having revolutionized Western philosophy, identified what he famously referred to as “the Categorical Imperative” with the moral law. For Kant, the Categorical Imperative, the supreme ethical principle, is a principle of universalizability, the philosophical equivalent of the much more memorable “Golden Rule,” the rule embodying the obligation of all human beings to do unto others as they would want others to do unto them.

However, the Categorical Imperative of the Christian—what we may call the Christian Imperative—boils down to the imperative to be thankful.

Of course, there is no contradiction between affirming the Golden Rule and affirming what I am here calling the Christian Imperative to express gratitude. Quite the contrary: The Golden Rule, understood in the Divine Light in which Jesus understood it, contains within it the Christian Imperative to be forever and always thankful.

Nor does this understanding of the Christian Imperative undercut the traditional Christian insistence that, of the three “theological” virtues of faith, hope, and love, the latter is the greatest. That gratitude presupposes and implies these virtues should be obvious:

Recognition of the world as gift is intrinsic to an essentially, an exclusively, religious sensibility. It entails faith in God, the Supreme Giver, and hope for an ever-perfected relationship with Him. Yet the knowledge of the Giver as giver is at once knowledge of the Giver as lover. To love is to give and to give is to love.

In knowing God as Giver, we are in a position to affirm, without hesitation or qualification, St. John’s proclamation that God is Love.

Yet knowing what we do about the giver/receiver relationship, we also know that receivers are never just receivers and that being a receiver carries with it the obligation to give thanks.

This insight underscores another Scriptural truth: Faith in God demands nothing more or less than love of God and love of others. But to love is to give and, in the case of all human givers who, unlike the Giver of all givers, are also receivers, to love, then, is to give thanks to God for all that we have received.

And to give thanks to God is to love others for, not necessarily their own sakes, but the sake of the Giver who blessed us with being and all other good things.

The Christian tradition, to a greater degree than any other, underscores the fundamentally loving essence of ultimate reality. For Christians, and Christians alone, the triune character of God insures that from all eternity love belonged to the nature of the Godhead in that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit has each given wholly of Himself to the others in this perfect community of Persons.

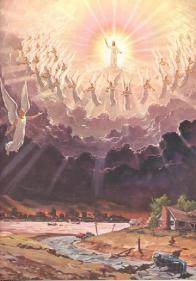

It is within the Christian worldview that Love becomes incarnate in the human being of Jesus of Nazareth so as to render it unmistakably clear to humanity that true love, and True Love, demand nothing less than the willingness of the lover to subject himself to the crucifixion of his selfish desires, his old self, in order to become a new creation. The Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ, who is God in the flesh, Love in the Flesh, teaches us a few things:

First, love is hard. Love inescapably involves suffering on the part of the lover.

Second, far from being incidental to it, the suffering that it entails is essential to love.

Third, this suffering is transformative. Just as the caterpillar doesn’t merely change into a butterfly, but is transformed into one, so love transforms those who it touches from an Earthly creature into a heavenly one, from an ego-centric biped into a child of God.

To be more precise, love is redemptive.

Finally, loving is self-giving.

Every act of love is a giving of oneself to others, and every time we so much as thank others for gifts received, however small and barely noticeable these gifts may be, we give ourselves, if only for the moment, to those to whom we give thanks.

In his Gratefulness: The Heart of Prayer: An Approach to Life in Fullness, Brother David Steindl-Rast observes that when the world is viewed as a grand gratuity, then life is seen a “great dance” in which “giver and receiver are one.” The author notes that while the recipient of a gift clearly depends upon the giver, “the circle of gratefulness is incomplete until the giver of the gift becomes the receiver: a receiver of thanks.”

But there’s more. In giving thanks, “we give something greater than the gift we received, whatever it was,” for the “greatest gift one can give is thanksgiving.” Steindl-Rast elaborates: “In giving gifts, we give what we can spare, but in giving thanks we give ourselves.”

The person who says “‘Thank you’ to another really says ‘We belong together.’ Giver and thanksgiver belong together.” The expression of gratitude precludes the condition of “alienation” that would otherwise be the human being’s lot in a Godless, material universe by binding together giver and receiver.

It is in gratitude, loving gratitude, that all beings are united together.

Recommended from Townhall

Who is online

438 visitors