'JFK' Review: The Road to Camelot

By: Philip Terzian (WSJ)

John F. Kennedy poses a problem for historians and chroniclers of American politics. He was a man of good looks, unquestioned charm and public eloquence. He was the Harvard-educated son of a wealthy New England financier, a decorated veteran of World War II and, not least, an acclaimed author of two books: a volume on foreign policy, written while he was still a college student, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning bestseller, produced while he was recovering from spinal surgery and a subsequent near-fatal infection. Kennedy was a shrewd member of the House and Senate, and his calculated rise to power was both swift and historic. In 1960 he became the youngest person ever elected president of the United States and the first (and, so far, only) Roman Catholic.

But, as every schoolboy knows, the best-known feature of the Kennedy presidency is that it was ended, in a ghastly tableau, toward the end of the third year of his single term when he was shot to death by a left-wing malcontent in Dallas. Whatever promise his brief tenure may have heralded was extinguished, leaving few tangible remnants. As his faithful acolyte Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. lamented, it was as if Franklin D. Roosevelt had been struck down in 1935, before the full flowering of the New Deal or World War II.

Nevertheless, in the immediate aftermath of his death, the challenge of concocting a legacy for our 35th president was quickly met. Kennedy had been a favorite among journalists and what we might call the cultural and intellectual caste in America; and he was, of course, a Democrat, though a somewhat unconventional one. So the man described, in 1965, by the British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge as “the easy-going, amorous, rather indolent and snobbish, amiable and agreeable American patrician of whom the late President’s intimates used sometimes to speak” had been transformed, by the end of the decade, into the Prince of Camelot, the lost leader of the better angels of our nature—a revered figure.

To be sure, in due course, the image has been revised and to some degree downgraded; but the mythology has been resilient. When Kennedy died, in 1963, the previous presidential assassination 62 years earlier—of William McKinley (in 1901)—seemed like antiquity; by contrast, JFK remains very much with us.

Fredrik Logevall, a diplomatic historian at Harvard, is aware of Kennedy’s “larger-than-life status.” But, he explains, “few serious biographies . . . have been attempted, and there exists virtually no full-scale biography, one that considers the full life and times and makes abundant use of the massive archival record now available.” He may well be right, although it’s hard to think of many presidents more voluminously chronicled than Kennedy.

But fair enough: In “JFK,” the first installment of a projected two-volume biography, Mr. Logevall takes Kennedy from his origins to age 39 and his debut as a national phenomenon at the 1956 Democratic National Convention, where, in the last genuinely contested balloting at a party conclave, he came within a handful of votes of winning the vice-presidential nomination. “To recapture him,” Mr. Logevall writes, “one must examine him when he was young and untried, still finding his way in his large and competitive Irish Catholic family and in the world, still learning what he was about.”

Does the author succeed? He certainly shows Kennedy to be, early on, less assured and worldly-wise than he became by the time he entered politics. He records as much as may possibly be known about the formative episodes in Kennedy’s life and career. He reminds us of his brilliant and diabolically ambitious father, Joseph P. Kennedy, whose wealth and world-wide connections afforded his more subtle and judicious son an enviable front-row seat at the mid-20th century—as well as plenty of money and timely assistance. Kennedy’s chronic ill-health is also recorded in startling detail: periodic episodes of weight loss, high fever, debilitating pain, physical delicacy and melancholy—not all of it attributable to the Addison’s disease that went undiagnosed until surprisingly late in life.

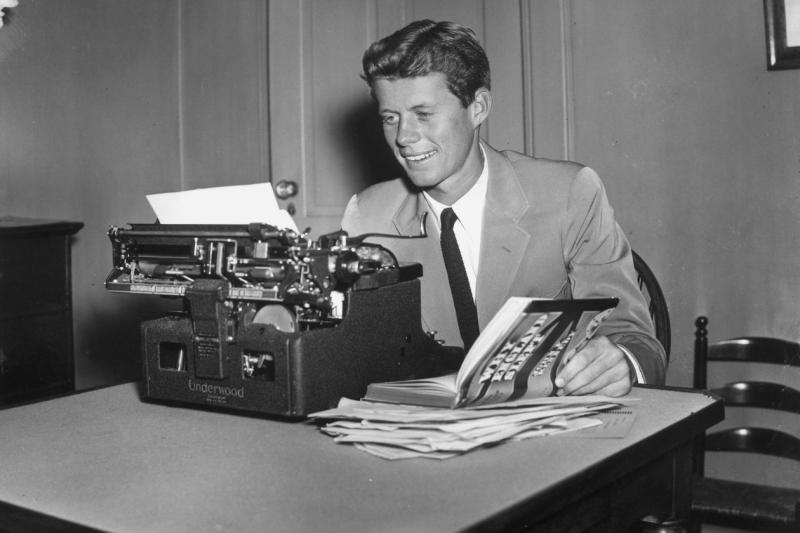

In his broad interests and extended apprenticeship, JFK comes across as the most intellectually adventurous, certainly the most personally appealing, member of the famous quartet of Kennedy brothers. Jack’s Harvard thesis, subsequently published as a slim volume titled “Why England Slept” (1940), was constructed with considerable assistance from well-placed enablers and pushed onstage by his father’s contacts and promotional skills, a process repeated for the (largely) ghostwritten “Profiles in Courage” (1956). But it’s difficult to imagine Joe Jr., Bobby or Teddy embarking on similar projects.

And yet, in the long run, Mr. Logevall labors a little too strenuously to persuade readers that Kennedy was more than the product of his family’s privilege and his own ambition and modest talents as intellect and interpreter of the world. The facts of his evident sexual appeal are repeated, and repeated again, with undue emphasis; his undergraduate insights and gathering worldview in office are recorded in admiring abundance. “JFK” is replete with testimonials to his ample qualities, yet nearly all of them are post-mortem assessments from the Kennedy circle. (“There was a basic dignity in Jack Kennedy, a pride in his bearing,” says one of his longtime aides.) His coterie of intimate male friends contained a revealing quantity of toadies, hangers-on and partners in pleasure. Not surprisingly, they have fond memories of Jack.

The legend, in other words, has been as hard for Mr. Logevall to penetrate, much less overcome, as for any of his predecessors in biography. One comes away from “JFK” suspecting that, the more detail we have of this truncated life, the less majestic it will appear to posterity.

Mr. Terzian, a contributing writer at the Washington Examiner, is the author of “Architects of Power: Roosevelt, Eisenhower, and the American Century.”

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Debunking Camelot? Or do we finally have someone writing a biography of JFK who is not an ardent admirer?

The review begins by acknowledging how difficult it might be to write an unbiased assessment.

We have other marble men in our history. It is only over time, as passions fade, that we get to have a clearer picture of the man.

Coincidentally, I've been reading another biography of Kennedy, An Unfinished Life by Robert Dallek. The author's excuse making over Vietnam is a little excessive, but it's pretty interesting. It really drives home what terrible shape he was in physically, he was addicted to pain pills. It's also drives home how standards have changed. His womanizing would put Trump to shame. Leaving Jackie to find her way home at parties while he took off with some one night stand was pretty common behavior. He was very lucky the media protected his image.

As we get farther away from the romanticized version that was peddled to the country, his reputation will continue to suffer. He was not a terrible President, but he certainly benefited from a media eager to canonize him.

It was also funny to read about Khrushchev telling the Politburo that they got Kennedy elected.

I love it. I believe there were others who made the same claim, starting with the mayor of Chicago.

The author's excuse making over Vietnam is a little excessive

They have to do that, you see Khrushchev had JFK backing down all over the world. Kennedy told a Times reporter that he would draw the line at a place called Vietnam. What did you think of the coups that Kennedy gave the green light to?

Sean, I'm just glad to hear that we have members who read books.