'The Bloody Flag' Review: Seas of Unrest

By: A. Roger Ekirch (WSJ)

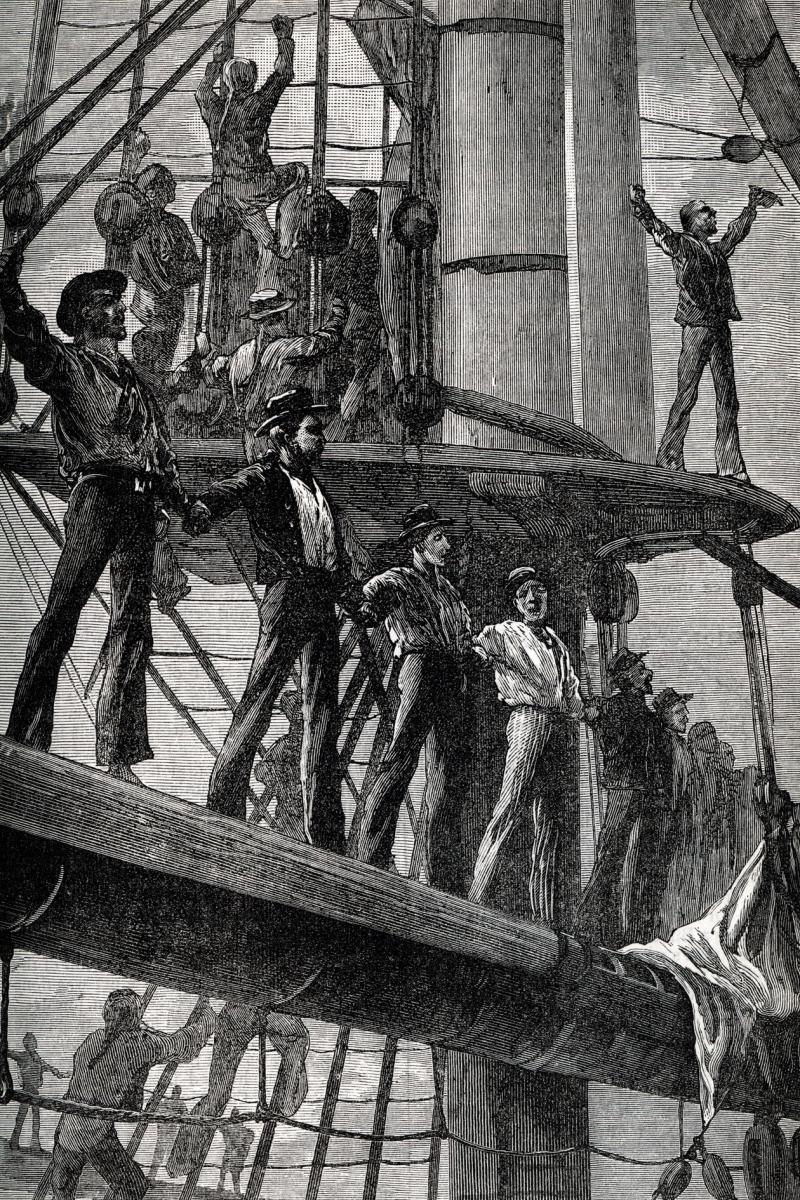

The 1789 mutiny aboard the Bounty in the course of its scientific expedition in the South Pacific remains the most famous maritime uprising of its era, and perhaps of all time. But in “The Bloody Flag: Mutiny in the Age of Atlantic Revolution,” Niklas Frykman portrays an era of lower-deck turbulence of far greater magnitude. In the midst of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), mutiny was a constant threat to the British, French and Dutch fleets of the North Atlantic and the Caribbean. Mr. Frykman, an assistant professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, estimates that by the early 1800s, from one-third to one-half of seamen in the North Atlantic had been involved in at least one mutiny.

Most uprisings, according to this slender, informative volume, embodied a radical maritime culture that would not again arise on such a spectacular scale until the 20th-century revolts in Kiel and Sevastopol. More than 150 single-ship mutinies erupted at the close of the 18th century, plus multiple fleet-wide insurrections. (A comprehensive appendix with information for each revolt would have been a useful addition.) Most sensational were the Great Fleet mutinies off southern England in the spring of 1797, first at Spithead, near Portsmouth, followed shortly afterward by a more extreme uprising—the so-called “floating republic”—at the Nore, an anchorage at the mouth of the Thames.

Seamen’s grievances abounded: On top of grueling labor, disease, flogging, poor pay, inadequate shore leave and cramped quarters, numerous sailors were forcibly impressed into naval service. So dilapidated were some French ships that they were called by their own crewmen “drowners.” As if all this weren’t bad enough, Mr. Frykman emphasizes the damaging shift in paternalistic relations between officers and seaman underway by the 1790s, particularly in the British navy. “Where previously there had been at the core of the shipboard social order a close bond between the officer corps and the most highly skilled men on the lower deck,” he observes, “after several decades of reform to make the navy a more efficient, centralized, and authoritarian institution, that close connection had eroded.”

Meanwhile, the French Revolution loomed in the imagination of sailors and admirals alike, whether as a celebration of liberty or a nightmare of mob rule. In “Billy Budd,” Herman Melville captured the emotions that underlay the Great Fleet mutinies: “Reasonable discontent growing out of practical grievances in the fleet had been ignited into irrational combustion as by live cinders blown across the Channel from France in flames.”Mr. Frykman acknowledges that shipboard casualties during the unrest of the 1790s were typically slight, with many mutinies more akin to strikes than to revolts. They lasted from a day or two to several months, such as when ships in French ports refused to weigh anchor. Most, moreover, were failures, frequently followed by the execution of hard-liners. That uprisings often occurred on ships at sea in time of war raised the stakes for naval superiors. The Spithead mutiny ended peaceably as the Admiralty made concessions on pay. The Nore mutineers, however, took on a more radical cast, and the most militant sailors threatened to seek haven in French ports. Out of several thousand mutineers, more than 25 were hanged, including Richard Parker, the elected “president.” Otherwise, class war rarely “replaced the war between nations,” with “only few instances of crews refusing to enter combat” against enemy fleets.

Despite demonstrations of “solidarity,” discord flared within mutinous crews, sometimes reflecting Irish-English animosity. A few conspiracies, owing to leaks, died at birth. In an odd twist, French warships, following the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, occasionally refused to implement government decrees. It was no small irony that Robespierre and his fellow Jacobins, insisting upon complete submission, incurred the ire of ever more radical crews determined to preserve popular sovereignty at sea. The butcher’s bill for such defiance was steep. In early January 1794, four mutineers from the French warship America, after being seized and convicted of a “counter-revolutionary crime,” were executed aboard a floating guillotine before the entire fleet anchored at Brest.

One mutiny, aboard HMS Hermione in 1797, draws Mr. Frykman’s special attention. Occurring off western Puerto Rico on the night of Sept. 21, it arose in large part, the author contends, because of the collapse of the Great Fleet mutinies and smaller revolts. “The crew of the Hermione had had enough,” he writes. “They decided to answer violence with violence, and judicial terror with treason.” In a crescendo of maritime radicalism, the ill-fated ship suffered the most violent revolt in the chronicles of the Royal Navy. In addition to the captain, the inexperienced and sadistic Hugh Pigot, nine officers were murdered with cutlasses, axes and tomahawks before being launched overboard. One marine lieutenant, “out of his mind in a Fever,” was carried from his cot in a sheet and cast over the side. Although the author inexplicably discerns in this orgy of bloodletting a semblance of due process, only the fate of the master, with valuable navigational skills, was put to the crew and his life spared.

With a majority of the crew, upward of a hundred or more, eluding capture, the Hermione revolt stands as one of the most consequential and successful mutinies in naval history. An indeterminate number fled to the United States, of whom one, Thomas Nash, was extradited to the British with the unthinking approval of President John Adams. Such was the outrage among Americans, already incensed by the impressment of the country’s seamen, that this fresh act of British “tyranny” helped Thomas Jefferson win the tumultuous election of 1800. Nash’s subsequent execution also led directly to America’s adoption of political asylum for European fugitives. In addition to a handful of liberal reforms implemented by the Royal Navy, the prospect of finding refuge in the United States—mutineers included—was arguably the most noteworthy legacy of this chaotic age of naval turbulence.

Mr. Ekirch is a professor at Virginia Tech and the author, most recently, of “American Sanctuary: Mutiny, Martyrdom, and National Identity in the Age of Revolution.”

Who is online

37 visitors