'The Man Who Ran Washington' Review: Invisible Touch

By: Tevi Troy (WSJ)

A first-term White House chief of staff faces three great tasks: avoid scandal, get the president re-elected and leave without getting fired. It is remarkable how few chiefs of staff, over the past several decades, have accomplished all three. But James A. Baker managed to do so, guiding Ronald Reagan’s White House in the early 1980s and going on to powerful cabinet positions under Reagan and George H.W. Bush. In “The Man Who Ran Washington,” veteran reporters Peter Baker (no relation) and Susan Glasser, a husband-and-wife team, offer an illuminating biographical portrait of Mr. Baker, one that describes the arc of his career and, along the way, tells us something about how executive power is wielded in the nation’s capital.

Mr. Baker’s résumé was impressive well ahead of Reagan’s victory. The scion of a wealthy Houston family and a prominent lawyer, he served in Gerald Ford’s Commerce Department and ran Ford’s 1976 campaign for president, as well as, four years later, George H.W. Bush’s campaign in the Republican primaries. The authors tell us that Mr. Baker first came into Reagan’s orbit by way of Bush, with whom Mr. Baker played tennis at a Houston country club. (Tennis is mentioned 36 times in “The Man Who Ran Washington”; the authors say that the game and its networking effects, early on, played a role in getting Mr. Baker into Washington politics in the first place.) After serving as Treasury secretary in Reagan’s second term, Mr. Baker ran Bush’s 1988 presidential campaign and, after the election victory, became his secretary of state. We learn that Mr. Baker was even offered the job of Defense secretary early in George W. Bush’s second term. It is the rare Washington power broker whose status has stood so high for so long.

As the authors make clear, Mr. Baker flourished in each of his positions because of his adherence to what might be called the Baker Method: working hard, maintaining smooth relationships with Congress, relying on a recurring team of talented aides, and, of course, keeping up a constant stream of media leaks to guide journalists and reinforce the Baker narrative. Mr. Baker was not above stepping away from a situation when things were headed in a bad direction—in 1992, for example, he was careful to avoid giving a speech touting George H.W. Bush’s proposed second-term economic agenda just when it seemed clear that Bush was unlikely to win the upcoming election. Nor was he reluctant to undercut adversaries: In the Reagan White House, he frequently clashed with Ed Meese, the counselor to the president, calling him “Poppin’ Fresh, the doughboy” and maneuvering him out of his foreign-policy responsibilities. But Mr. Baker didn’t hold grudges. Years after retiring from government service, he was called back to co-head the bipartisan Iraq Study Group. When Rudy Giuliani neglected to show up to the group’s meetings, and Mr. Baker needed another Republican to fill his shoes, he offered the position to his old rival Mr. Meese, who graciously accepted.

In their comprehensive narrative, the authors show that, while Mr. Baker was gliding from position to position and success to success, he was also dealing with a challenging personal life. His first wife, Mary Stuart (née Mary Stuart McHenry), died of cancer in 1970, when she was just 38 years old, leaving him with four rambunctious young boys. In 1973, he married Susan Garrett Winston, a friend of his first wife and the ex-wife of one of Mr. Baker’s own friends (who was suffering from alcoholism and eventually died of it). Susan brought three kids of her own to the union, and together they had another child, bringing the total number of this Brady-esque household to eight.

While Mr. Baker was running Washington, Susan was running the household and, at times, suggesting to her husband that his lack of focus at home had consequences. The children experimented with drugs and alcohol; Mr. Baker was not always aware of the extent of the problem. There is a telling exchange in the book, taken from the authors’ 70 hours of conversation with Mr. Baker (now age 90) at his home in Houston and elsewhere. “I think every one of our kids, with the possible exception of Bo and Mary-Bonner”—two of the youngest children—“tried drugs at one time,” Mr. Baker says. Susan shakes her head and responds, “Honey, Bo was the ringleader.” Mr. Baker tries again: “But MB never did, right?” At this, Susan smiles, asking: “Shall I burst the bubble?”

While Mr. Baker was serving as Reagan’s chief of staff, his son John was arrested on drug charges. Some media outlets reported it, but the story remained largely under the radar. The quiet treatment happened in part because it was a different time, when the press was less eager to reveal the personal lives of political figures, and in part because Mr. Baker, because of the inside intelligence he constantly offered up, had good relations with reporters. If he had been less popular, they might have had a field day with the son of the White House chief of staff being arrested at the same time that Nancy Reagan, the first lady, was launching her “Just Say No” campaign.

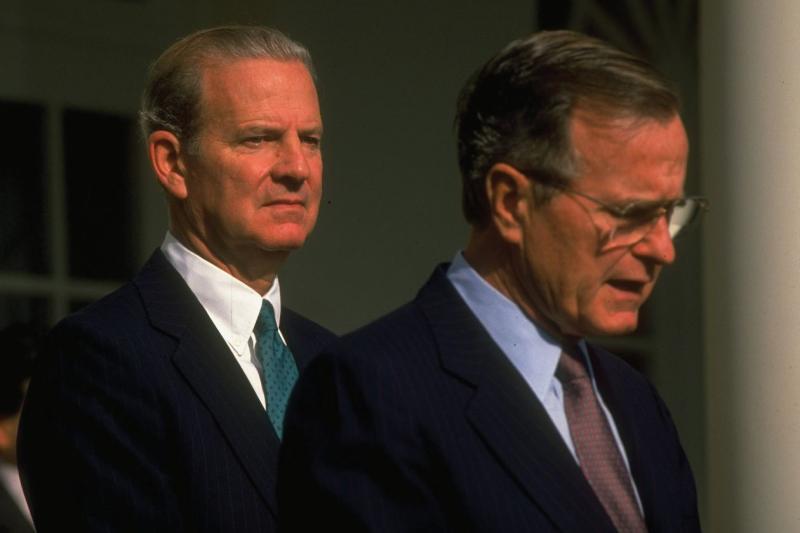

Inevitably a major figure in “The Man Who Ran Washington” is George H.W. Bush, Mr. Baker’s patron and friend, though their relations didn’t always run perfectly. The Bush family apparently resented Mr. Baker for ending up as chief of staff to Reagan after advising Bush to pull out of the 1980 primary campaign. According to the authors, Bush developed a “frivalry” with Mr. Baker over his secretary of state’s ability, in the midst of controversy or political challenges, to come out smelling like a rose—again, helped by Mr. Baker’s press management. When Mr. Baker reluctantly returned to the White House from the State Department to try to right Bush’s floundering 1992 re-election campaign, he raised hackles again. Barbara Bush was so disappointed with his absentee performance that she tagged him “the Invisible Man.”

As for Mr. Baker’s political outlook, he has long been taken for a pragmatist, perhaps less ideologically driven than many of the people who served in the administrations of Reagan and George H.W. Bush. The authors note: “When pressed, he insisted he was every bit as conservative as any other Reagan adviser. He was from Texas after all. But unlike the purists, he understood how to get things done.” On the foreign-policy front, there was clearly disconnect between Mr. Baker’s approach to the Middle East—he favored, for instance, pressuring the Israelis to make concessions to the Palestinians—and the increasingly ascendant pro-Israel tilt of the GOP.

“The Man Who Ran Washington,” thanks in part to the authors’ dozens of meetings and hours of conversation with their subject, often has the feel of a novel related by an omniscient narrator. The book is far from hagiography, but Mr. Baker is often allowed to communicate his perspective, clearly and comprehensively—the very approach that helped him succeed so spectacularly during his long and impressive run in politics.

—Mr. Troy, a presidential historian and former White House aide, is the author of “Fight House: Rivalries in the White House From Truman to Trump.”

Who is online

37 visitors