'The Zealot and the Emancipator' Review: A Deadly Confrontation -

By: WSJ

‘How does a good man challenge a great evil?” Fittingly, H.W. Brands asks this question at the outset of “The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom.” The great evil was slavery, and the subjects of Mr. Brands’s dual biography were the two most famous martyrs in the struggle against it. Recounting their parallel lives, Mr. Brands offers two diametrically opposed answers to his initial question.

Lincoln once compared slavery to a poisonous snake coiled in the bed with his children. The metaphor was designed to show why the Republican Party opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories but not immediate abolition where it already existed. No decent father would allow a snake to slither into his children’s bed, Lincoln said. But a father who found the snake already there must be careful. “Would I do right to strike him there? I might hurt the children; or I might not kill, but only arouse and exasperate the snake, and he might bite the children.”

Lincoln was not suggesting, like many slaveholders, that abolitionists threatened the physical safety of whites in the South. He expressly dismissed such fears as absurd. The real danger was that slavery would corrupt the devotion of Americans to their own national creed. “Familiarize yourselves with the chains of bondage, and you are preparing your own limbs to wear them,” Lincoln warned in 1858. Slavery was as old as sin. But the nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal was young and fragile—as vulnerable, in Lincoln’s eyes, as a sleeping child. His task was to preserve the nation from an evil that menaced it.

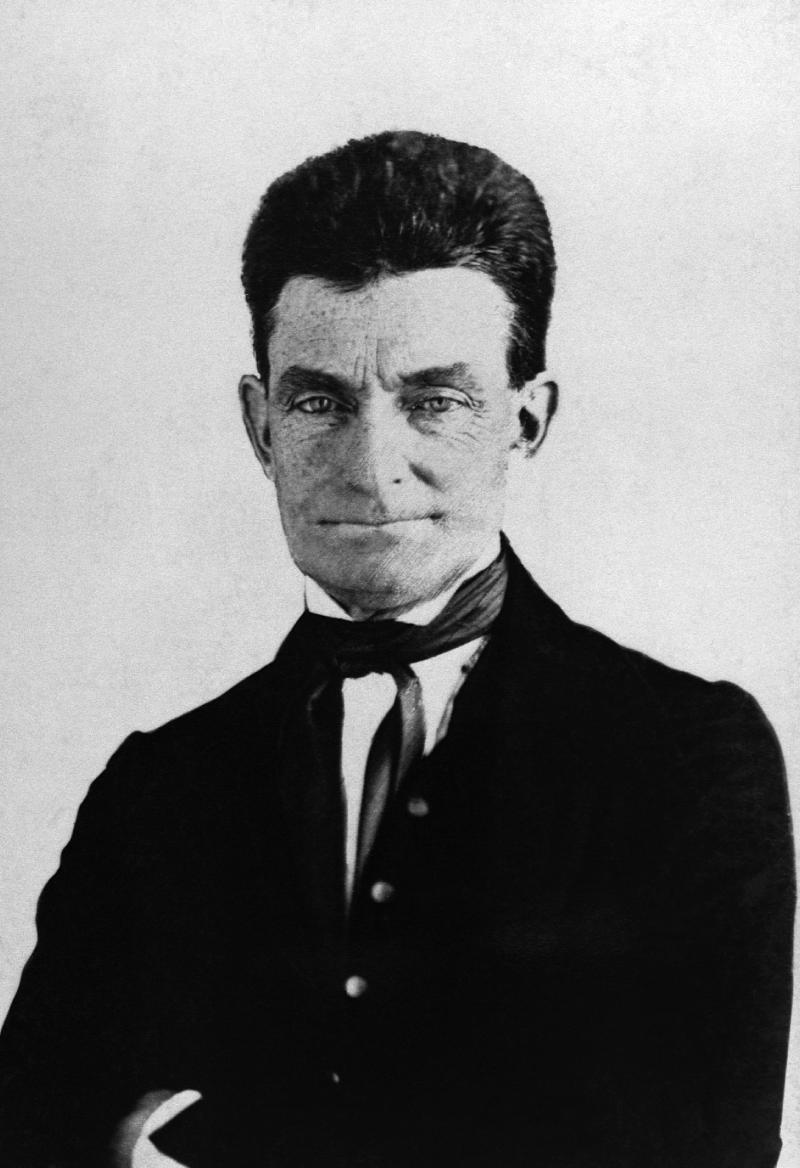

John Brown had a different purpose. “The crimes of this guilty land, will never be purged away; but with blood,” he wrote in 1859, just before he was hanged for treason. As the sectional conflict over slavery escalated in the 1850s, Brown did more than anyone to transform a moral impasse into a civil war.

Born in 1800, Brown was an old man when he began to make his mark on history, a failed businessman, the object of multiple lawsuits and the father of 20 children. American history is full of controversy, but no figure remains as polarizing as Brown. Historians have dismissed him as a lunatic, condemned him as a terrorist and canonized him as a hero. Mr. Brands, a history professor at the University of Texas, scrupulously narrates the relevant facts and trusts readers to form their own conclusions.

Between 1854 and 1856, as Kansas settlers prepared the territory for statehood, proslavery and antislavery partisans struggled to align its future with the North or the South. Like many riotous cities this past summer, the territory became a magnet for ideological fanatics and well-meaning fools, making life miserable for settlers primarily interested in earning a living. As Lincoln argued for excluding slavery from the territory in countless speeches, John Brown traveled there with a wagon full of weapons, ready for war.

“I mean to steal a march on the slave hounds,” Brown declared in May 1856. He and several followers, including four of his sons, targeted the Pottawatomie settlement in the middle of the night. Their first victim was James Doyle, who was asleep in a modest cabin with his wife and three sons when Brown’s so-called Army of the North knocked on his door. Brandishing pistols and broadswords, they kidnapped Doyle and two of his sons, sparing the youngest boy after his mother begged for his life. Mahala Doyle heard her husband and sons being murdered, and her youngest son discovered their corpses the next morning.

Brown’s militia continued its ghoulish campaign at the homes of two more sleeping settlers, claiming a total of five victims. None of them were slaveholders, and despite a mountain of scholarship on the incident, no one knows exactly why these men were singled out for murder.

The Pottawatomie massacre made Brown infamous in Kansas. But his antislavery allies outside the territory dismissed the story as a smear. “To the armchair abolitionists of New England,” Mr. Brands writes, “he was a great hero.” They hosted Brown in their homes and raised money for his endeavors. Into his grim appetite for righteous violence they projected their own lofty ideals. “I think him about the manliest man I have ever seen,” Bronson Alcott, the father of Louisa May Alcott, wrote as Brown prepared for an even more audacious adventure.

In October 1859, Brown invaded Virginia (present-day West Virginia) with 21 men, intending to seize the arsenal at Harpers Ferry as the beginning of a general uprising against slavery. “When I strike,” Brown predicted, “the bees will begin to swarm.” It didn’t turn out that way. As Lincoln later put it, the effort “was so absurd that the slaves, with all their ignorance, saw plainly enough that it could not succeed.” Their masters, however, took the incident far more seriously. Brown’s futile raid created a sense of crisis in the South that paved the way for the secession movement a little more than a year later.

“The Zealot and the Emancipator” relates these familiar events skillfully without pretending to offer new material or original interpretations. The final 150 pages gallop through the Civil War, quoting extensively from Lincoln’s most famous works, with cursory paragraphs providing context.

But Mr. Brands, who has written about nearly every era of American politics, seems to recognize that the contrast between Brown and Lincoln offers a lesson that has never been timelier. Prudence and idealism are complementary virtues. And zeal unencumbered by a concern for consequences is indistinguishable, in practice, from bloodlust.

Lincoln compared Brown to a political assassin who substitutes a single mad act for the constructive efforts that sustain political freedom. One future assassin, who detested Brown’s politics, couldn’t resist admiring a fellow maniac. “John Brown was a man inspired,” John Wilkes Booth declared, “the grandest character of the century!”

Mr. Rowe is a historian in Dallas.