‘Stalin’ Review: From Periphery to Power

By: By Joshua Rubenstein

Not surprisingly, Joseph Stalin has been the subject of many biographical studies, in recent years in particular, when formerly closed Soviet archives became open to students of history. Decades before, Leon Trotsky, Isaac Deutscher, Adam Ulam and Robert Tucker, to name a handful of prominent authors, wrote hefty volumes on Stalin’s life, attempting to tell the story with limited information. Their work has been surpassed by another generation of scholars, led by Dmitri Volkogonov, Robert Service, Oleg Khlevniuk and Stephen Kotkin. They have plumbed the archives and benefited from a host of memoirs that have deepened our understanding of a murderous dictator whose legacy, nearly 70 years after his death, still haunts the countries he once ruled.

Ronald Grigor Suny’s “Stalin: Passage to Revolution” is a worthy contribution to this continuing enterprise. “The telling of Stalin’s life has always been more than biography,” Mr. Suny writes. “There is wonder at the achievement—the son of a Georgian cobbler ascending the heights of world power, the architect of an industrial revolution and the destruction of millions of the people he ruled, the leader of the state that stopped the bloody expansion of fascism.” It is the story of how the Romanov dynasty, convinced of its own divine right to rule the Russian Empire, confronted “a newly emerging social class” of industrial workers, a clash that “exploded into violence, bloodshed, and eventually revolution.” Reading Mr. Suny’s chronicle, one can’t help recalling John F. Kennedy’s remark, in a 1962 speech, that “those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

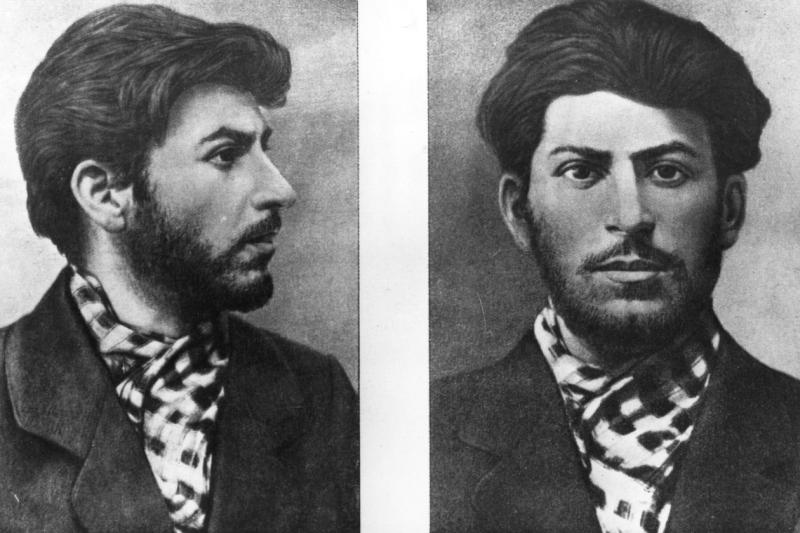

Mr. Suny’s focus is Stalin’s early decades, from his birth and education to the eve of revolution in 1917. Born in 1878 in the Georgian town of Gori, on the southern periphery of the Russian Empire, Ioseb Jughashvili, as he was christened, was raised in a poor family. His father scratched out a living as a cobbler; his mother was a religious woman who worked as a seamstress. The couple had lost their first two sons in infancy, driving his father to become “violent, erratic, and drunk,” Mr. Suny says, and to abandon the family. Convinced of Joseph’s abilities, his mother worked to gain his admission to a seminary so that he could become a priest.

Using his access to archives in Georgia, Mr. Suny describes the milieu in which the young Joseph grew up—the children’s games he enjoyed and the literature and myths that animated his imagination. It was at the seminary in the Georgian capital of Tiflis that the teenage Joseph confronted the obstinacy of his teachers, who denigrated Georgian culture and insisted on the primacy of Russian language and history. Life at the seminary, Mr. Suny writes, was “colorless and monotonous . . . , a strict routine designed to inculcate obedience and deference.” It proved to be as much a “crucible for revolutionaries as for priests” and pushed “an intelligent but still quite ordinary adolescent into opposition.” At the seminary, Joseph “came to socialism through reading and the fellowship of classmates.”

In highly readable prose Mr. Suny, a history professor at the University of Michigan, tells the story of the young Stalin’s rise within the ranks of the Bolsheviks, its disputes with the more moderate Mensheviks, and his frequent arrests and terms of imprisonment and exile. Stalin, known as Koba to his comrades, made a name for himself as a party organizer in the Caucasus, among miners and oil workers. Here confrontations with czarist officials were violent and bloody, marked by heists and assassinations.

Stalin closely studied the works of Marx and, not least, the writings of Lenin before he met the Bolshevik leader in 1905, an encounter that began a close and fateful association. Mr. Suny’s close study of these years uncovers the traits of suspicion and intrigue that came to define Stalin in power. Koba, he writes, “was not above using dubious means against comrades with whom he disagreed,” lying about them behind their backs to compromise their standing. In his encounters with Mensheviks, he indulged in anti-Semitic insults, knowing that there were more Jews among them than among the Bolsheviks he favored.

Mr. Suny’s account of the tensions between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks is spirited and compelling, especially when he describes these ostensible allies splitting into “antagonistic cultures,” each demonizing the other over their motives, making reconciliation ever less likely. Lenin is often at the center of this story, engaging in vicious polemics against his ideological adversaries. Regrettably, Mr. Suny’s account briefly falters when he writes about Lenin’s return toRussia in the spring of 1917 on a “sealed train.” Lenin not only relied on the cooperation of German officials to make the journey but also accepted German gold to support the Bolsheviks’ efforts, a well-documented claim that Mr. Suny doesn’t accept. (Germany was still at war with Russia, making Lenin vulnerable to the charge of treason.)

With his focused attention on Stalin, Mr. Suny also goes too far in trying to correct earlier scholars and figures who played down Stalin’s role in the October Revolution. Stalin may not have been a “gray blur,” as one Menshevik writer put it. Even so, he was not, as Mr. Suny depicts him, among the decisive players who made the revolution. While his newspaper work and party organizing in Petrograd made him a reliable comrade to Lenin, it was Lenin and Trotsky who directed Bolshevik strategy, dispatching soldiers and sailors to bring down the provisional government in October.

Stalin’s moment came in March 1922, when Lenin elevated him to the position of general secretary, handing him so much control of the party that upon Lenin’s death in 1924 he could outmaneuver the more prominent, but politically overmatched, Trotsky. It was then that the poor Georgian boy, who devoted himself to a movement that claimed to stand for equality, rose to become a tyrant. History is full of such figures. They dream of emancipating humanity and then, once in power, enslave millions.

Mr. Rubenstein’s most recent book is “The Last Days of Stalin.”