‘This Time Next Year We’ll Be Laughing’ Review: Fruits of Memory

By: By Anna Mundow

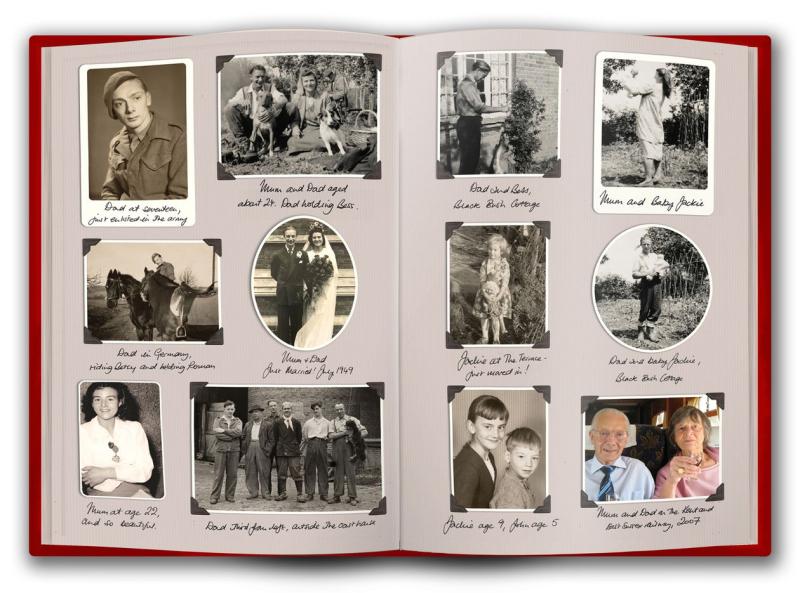

When Jacqueline Winspear was 4 years old she was given a child-size set of cleaning rags—for housekeeping, not for playing house. She already had her own garden shovel, her own tool kit and almost as soon as she could walk had become a seasonal picker in the fruit fields of England. “By fourteen I’d picked every kind of fruit grown in Kent,” Ms. Winspear writes in her new memoir, noting that even “strawberry plugging” was not as bad as working in the local egg packing factory, which, as a teenager, she also did. From her earliest days, then, she had worker’s hands. Indeed, in the cover photograph here—of a little girl in straw hat and summer dress, her serious gaze sliding off to the side—those hands, holding a bunch of hops, seem older than she is. And at her feet is her picking basket.

As the child of working-class parents in postwar Britain, young Jackie was hardly an exception. But hard times were not the only spur to work. “A job was always thought to be balm for any distress to the soul in our house,” Ms. Winspear explains. And in the wake of two world wars, there was no shortage of distress. Jackie’s mother, one of 10 children with a violent, drunken father, was evacuated from London in 1939 to the countryside, where she and her sisters were horribly abused. And Jackie, born in 1955, was raised on reminiscences of the evacuation, the Blitz, dead children being pulled from rubble, a downed German pilot being hanged in an English strawberry field. “My mother had to tell her stories,” Ms. Winspear explains, “so she told the person who was around her all the time. She told me.” (The child also witnessed her shell-shocked grandfather, a survivor of the Somme, stabbing her beloved doll in a frenzied flashback.) Later came her mother’s increasing fragility due to Graves’ disease. And underlying all of this was the daily round of “not enough money . . . worry . . . not enough money . . . worry.”

Yet the title of Ms. Winspear’s candid yet fond memoir, “This Time Next Year We’ll Be Laughing,” carries not a whiff of bitterness and only gentle irony. A favorite phrase of her father’s, who had his own share of wartime misery at home and in Germany, the sentiment expressed his generation’s wry optimism. It emerges here as quiet nobility, most movingly captured in Ms. Winspear’s recollection of sitting at her dying father’s bedside in 2012.

We spoke of this and that for a while, ordinary things . . . then Dad turned and reached toward my mother, taking her hands in his own.

“Haven’t we had a great life?” he said.

She leaned her head toward his, pulled back one hand and rested it against his cheek. He moved his head and kissed her palm.

Leaving them alone, their daughter stands in the hospital corridor, poleaxed by love and grief, “reading and rereading the wall-mounted instructions for evacuation in case of fire.” A model of contained emotion, the scene exemplifies the light touch that has attracted millions of readers to Ms. Winspear’s fiction, in particular to the Maisie Dobbs mystery novels set predominantly in 1930s Britain. (A stand-alone novel, “The Care and Management of Lies,” depicts World War I.) For each plot that tests “psychologist and investigator” Maisie Dobbs also contains a shrewd portrait of an era and a character in flux. “Change is woven into the fabric of my stories,” Ms. Winspear observes, “probably because when I was a child the dueling senses of belonging and being out of place were ever-present.”She was born in Kent, where her parents, like many Londoners, picked hops during the summers and had lived as a young couple in a “gypsy” caravan alongside a Romany woman who taught Joyce Winspear how to make and sell paper flowers, a basket on her and hoop earrings glinting for added flair. And while that episode recalls the 19th-century world of George Borrow’s “The Romany Rye,” many other conjure up the pastoral world of Laurie Lee’s “Cider With Rosie.” Here summer mist wreathes fragrant orchards and golden fields. And country walks with her father, Ms. Winspear recalls, always meant “stopping to look, to watch, to see, to remember.”

A vigilant child (what with her mother’s moods and a fractious baby brother), she observed, as her family moved from farm to village, the solitary women bereaved by war, the blind and disfigured making their way. And those haunting figures, along with Romany culture, Kentish farm life, the tales of London’s costermongers, the characters of beloved dogs and the prejudices of a class-ridden society not only shaped Ms. Winspear’s childhood but also became central to her fiction. There is a lived quality to the Maisie Dobbs novels, an immediacy of place—as well as an acute rendering of manners and emotions—that owes much, it seems, to the clarity of Ms. Winspear’s own recollections. “Hardly an event happened that was not catalogued in my mind,” she writes of the heightened awareness that followed a scalding accident, “When I left the hospital . . . I started to remember almost everything that came to pass from then on.” She was just fifteen months old. “At times,” she adds, “I worked hard at forgetting.”

Wounds recur in Ms. Winspear’s stories and early life (for the past 30 years she has lived in California), but in this disarming memoir injuries yield to kindness. “I watched as my father put an arm around Grandad’s shoulders and asked, ‘All right, Dad?,’ ” she recalls of one childhood morning. “My grandfather nodded as Dad knelt at his feet and began massaging his legs which I could see now were lined with deep purple scars. Every now and again he would tease something out . . . splinters of metal from the war.” And in a deft coda, Ms. Winspear attempts to tease out the facts behind her mother’s more lurid stories, the ones that have haunted her daughter for 60 years. “I read the official account twice,” she writes of an oft-repeated episode involving an uncle at Normandy in 1944, “then sat back and thought, ‘She lied.’ ” Of other stories, however, she can only to conclude that “whatever the facts, my mother had shared her truth.” Which is good enough, ironically, for a writer whose fictional sleuth might not settle for such equivocation. But Ms. Winspear is, above all, a forgiving chronicler. And the final scene in this affecting evocation of a vanished England and a resilient generation is an unashamedly tearful one. Walking in the hills above the northern California coast, a world away from the fruit fields of Kent, she sights a whale and hears her father’s voice.

“See that, Jack? . . . Look where I’m pointing—follow my hand . . . I bet no one will ever believe us—we’ve seen a whale! . . . Very lucky, aren’t we, love?”

—Ms. Mundow is a writer in central Massachusetts.