Five Best: Novels on Slavery and the Civil War

By: Dorothy Wickenden (WSJ)

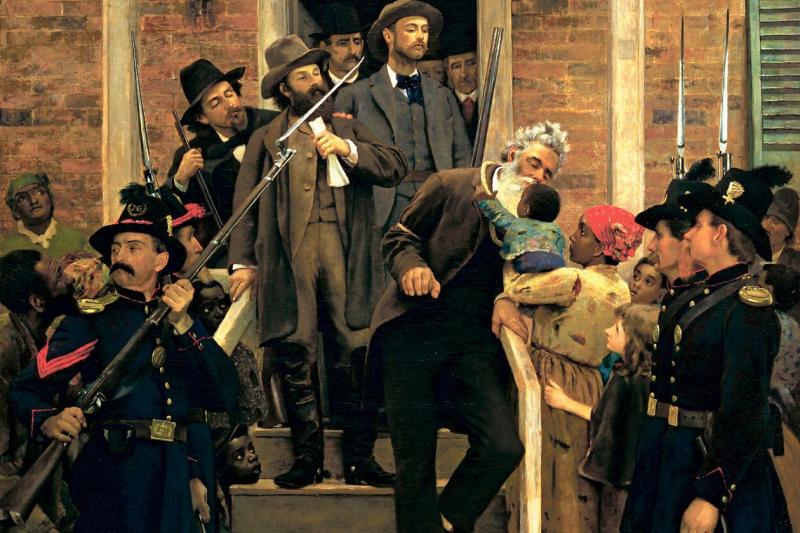

Thomas Hovenden's 'The Last Moments of John Brown' (ca. 1884).

By James McBride (2013)

1. James McBride's John Brown is a Bible-thumping, "low-down son of a bitch," a murderous zealot who looks "mad as a wood hammer" and whose infamous militia consists of a dozen of the "bummiest, saddest-looking individuals you ever saw." These are the early observations of the narrator, Henry Shackleford, an enslaved boy whom Brown mistakes for a girl and sweeps up in the wars of Bleeding Kansas. Henry "weren't for no fighting," but he accompanies Brown across the U.S. and into Canada as Brown flees the authorities and attempts to raise money and men. In this antic tale of the misadventures of the man who made the Civil War inevitable, Henry creates a portrait of Brown that grows fonder as the end approaches: "Pure to the truth, which will drive any man off his rocker. But at least he knowed he was crazy." Henry witnesses Brown's atrocities but also his tenderness and his puzzling commitment to fight "on behalf of the colored." Noting Brown's beatific smile before he is hanged, Henry says: "It was like looking at the face of God."

Henry and Clara

By Thomas Mallon (1994)

2. "Henry and Clara" established Thomas Mallon as a master of historical fiction. Clara Rathbone—vain, clever and socially ambitious—reflects, near the climax of this blood-drenched novel, that she always sensed "there was a secret sewn into the violence of that night." She is referring to April 14, 1865, when she and her fiance, Maj. Henry Rathbone, last-minute guests of the Lincolns in their box at Ford's Theatre, witness the assassination of the president. That much is true. But Mr. Mallon seamlessly blends fact and fiction in this sharply angled historic tableau. Clara's "blind love" for her Byronic stepbrother can only end tragically, and through Clara Mr. Mallon also conveys just how unprepared the North is for the cataclysm of the war. In the spring of 1861, when Clara learns that her father, U.S. Senator Ira Harris, will allow her semi-incestuous marriage as soon as the Union declares victory, she exclaims, "I'm so happy! Maybe this war is a blessing—God forgive me for saying it." Mr. Mallon, a stylish, witty writer, almost imperceptibly transforms his love story into a heart-stopping psychological thriller.

The Underground Railroad

By Colson Whitehead (2016)

3. "The lesson was unclear," Cora tells herself. No longer enslaved on the Georgia cotton plantation where she was raised, she finds that "misfortune had merely bided time: There was no escape." Relentlessly pursued by the Javert-like slave-catcher Ridgeway, she becomes accustomed to the sound of the lock on his wagon: "It hitched for a moment before falling into place." Ridgeway opines about "the American imperative": "To lift up the lesser races. If not lift up, subjugate. If not subjugate, exterminate." In Colson Whitehead's dazzlingly inventive narrative, the underground railroad is an actual rail line that takes Cora through four hellish states—from an ostensible "new era" in South Carolina, where sterilization and scientific experiments are performed on free blacks, to temporary respite on a black farm in free-state Indiana. Like Cora, the reader cannot escape the hideous legacies of slavery, but Mr. Whitehead holds out some hope for a redemptive future through his heroine: discerning, fierce, indomitable.

The Killer Angels

By Michael Shaara (1974)

4. Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, a 34-year-old professor of rhetoric at Bowdoin College, thinks of Aristotle after he leads his bayonet charge on Little Round Top: In the presence of real tragedy, he concludes, "you feel neither pain nor joy nor hatred, only a sense of enormous space and time suspended." Michael Shaara's Pulitzer Prize-winning "The Killer Angels" doesn't so much re-create the three-day Battle of Gettysburg as inhabit it. Drawing on primary documents, Shaara climbs inside the minds of the warring officers and invites the reader to experience the sights, sounds and smells of the killing fields. White-haired Gen. Robert E. Lee's bad heart leaves him with "a sense of enormous unnatural fragility, like hollow glass." The Yankees hold the superior position in the hills outside town, but Lee disastrously refuses to consider the defensive maneuver urged on him by his second-in-command, James Longstreet. After the defeat, he concedes, "It is all my fault, it is all my fault." As dusk falls, Chamberlain sits alone on the rocky hill, his mind "blasted and clean," watching men moving below him with yellow lights, "from black lump to black lump while papers fluttered and blew and fragments of cloth and cartridge and canteen tumbled and floated against the gray and steaming ground. . . . It rained all that night. The next day was Saturday, the Fourth of July."

Washington Black

By Esi Edugyan (2018)

5. This wondrous adventure story, punctuated by scenes of gruesome violence, begins in 1830. Young George Washington Black, a field hand on a Barbados sugar plantation who is about to lose his life for a murder he did not commit, is whisked away in a hot-air balloon. Its inventor, Christopher, the abolitionist brother of the malign owner of the plantation, is an eccentric naturalist and explorer who has been tutoring "Wash." In Virginia, Wash refuses to join two fugitive slaves on the underground railroad, preferring to accompany Christopher to the Arctic, on an apparently crazed search for Christopher's father. Wash later makes his way to Halifax Harbor, where he becomes an expert in marine life. In Esi Edugyan's crystalline prose, Wash observes the bloom of jellyfish in a nighttime sea: "fragile as a woman's stocking, their bodies all afire." But he is not all sensitivity and introspection. Attacked one night by a mercenary, Wash stabs him in the eye with an ivory-handled kitchen knife, then takes flight on his own quest, to find Christopher, the man with whom "freedom seemed a thing I might live in, like a coat"—only to discover that what he actually seeks is to shed the fear of "accepting my own power."

Tags

Who is online

94 visitors

To be filed under "what should be part of the curriculum"......in all American schools

About this I am not sure, I was one of those rarities in High Schools who devoured 3 or more books a week consistently showing up in class with 4 a.m. sleep clinging to my eyelashes like stalagmites and stalactites. Out of the literally 1000's of books I have read I would be hard pressed to establish a reading curriculum that the average student would willingly consume ... adding a 'this is a must read' today would require removing a 'must read' from yesterday.

You may be right. The books would have to go on a list and students should get a choice.

James McBride Takes An Admiring, Humorous Look At John Brown

(not my usual swipe at you Vic ... just adding some meat to the bone and so far thumbs up ... I have yet to look at the other authors) Anywho ... a quote:

“There weren’t a dumb beast under God’s creation — cow, ox, goat, mule, or sheep — that he couldn’t calm or tame to touch. He had nicknames for everything. Table was ‘floor tacker,’ walking was ‘tricking.’ Good was ‘dowdy.’ And I was ‘the Onion.’ He sprinkled most of his conversation with Bible talk, 'Thees’ and ‘thous’ and ‘takest’ and so forth. He mangled the Bible more than any man I ever knowed, including my Pa, but with a bigger purpose, ‘cause he knowed more words. Only when he got hot did the Old Man quote the Bible exact to the letter, and then it was trouble, for it meant someone was about to walk the quit line. He was a lot to deal with, Old Brown.”

I'm sure you recall what Herman Melville famously called Brown.

May I?

The very word is a flood in my memories, alas that I could not sing along with:

but I could with: