The triumph of Thomas Sowell by John Steele Gordon

By: Jason L.

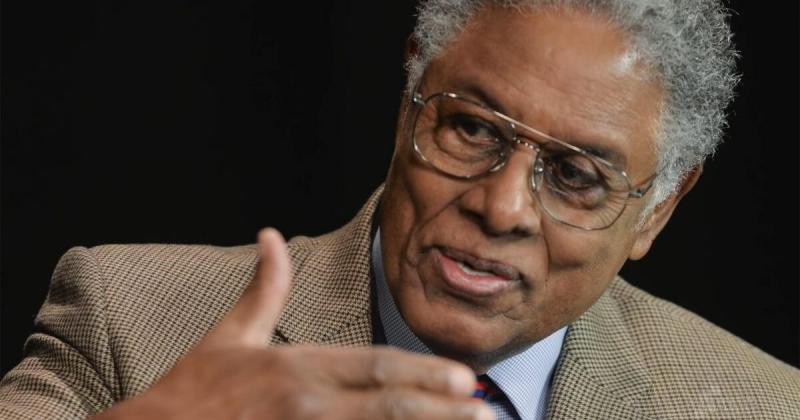

Thomas Sowell is one of the towering American intellectuals of our time. An economist trained at the University of Chicago and a social theorist of the first rank, he has been a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University since 1980.

He has written an astonishing fifty books (if you count revised and expanded editions), numerous essays, and a long-running, twice-a-week newspaper column. Extraordinarily wide ranging, he has covered everything from the rudiments of economics to race relations, the housing crisis of 2008 to late-talking children.

His best known book, Basic Economics (2000), a best-selling, chart-, graph-, and jargon-free introduction to the subject, is now in its fifth edition and has been translated into seven languages.

No less an authority than Milton Friedman, who taught Sowell at the University of Chicago, has said that "The word 'genius' is thrown around so much that it's becoming meaningless, but nevertheless I think Tom Sowell is close to being one."

So it's about time for there to be a biography of this remarkable man, although it should be noted that Maverick is far more an intellectual biography than a personal one.1 And we should be grateful to Jason L. Riley for writing a very good one. Riley is the author of Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to Succeed (Encounter). He is also a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a columnist at TheWall Street Journal.

Sowell's life did not get off to an easy start, to put it mildly. In 1930, the year he was born into a black family in Gastonia, North Carolina, the Great Depression was gathering strength. And Jim Crow was in full force, so he seldom encountered white people in his early years. As Riley explains, "He'd been turned away from restaurants and housing because of his skin color. He'd felt the pain and humiliation of racism firsthand throughout his life. He needed no lectures from anyone on the evils of Jim Crow."

His father had died a few months before his birth, and his mother, a housemaid, already had four children. So he was raised by a great-aunt.

The family moved to Harlem when he was nine, part of the great migration of black families from the South to the North in search of greater opportunity in those years. Forced to drop out of high school to get a job, he only went to college after a stint in the Marines during the Korean War.

He was the first member of his family to get beyond the seventh grade, and he was ignorant of even the basics of higher education. At first he thought that professors who were addressed as "doctor" were physicians as well as professors. "It came as a revelation to me that there was education beyond college," he wrote, "and it was some time before I was clear whether an M.A. was beyond a Ph.D. or vice versa. Certainly I had no plans to get either."

At first he attended night classes at the historically black Howard University. There, his professors noted his remarkable intellect and capacity for hard work and helped him transfer to Harvard the next year. He thrived there intellectually and graduated at the age of twenty-eight magna cum laude.

But he was less enamored of the social atmosphere in Cambridge. Sowell noted that he "resented attempts by some thoughtless Harvardians to assimilate me, based on the assumption that the supreme honor they could bestow was to allow me to become like them."

Chicago was not an imitation of anything. It was wholly itself.

He got his master's degree the next year at Columbia and intended to get his doctorate there as well, so he could study under George Stigler, who had written an essay on the early economist David Ricardo that Sowell had greatly admired. (It might be noted that the very first quotation in Sowell's Basic Economics, written many years later, is from George Stigler.) But when Stigler (who won a Nobel Prize in 1982) moved to the University of Chicago, Sowell followed him there. He was very glad he did.

For while Sowell thought Columbia was a sort of a "watered-down" version of Harvard, Chicago was not an imitation of anything. It was wholly itself.

And the economics department was extraordinarily rigorous. Ross Emmett, an authority on the economics department at Chicago, told Riley that "During that period of time, Harvard took in twenty-five to twenty-seven students and graduated twenty-five of them, whereas Chicago took in seventy students and graduated twenty-five of them." In the fifty-two years that Nobel Prizes in economics have been awarded, no fewer than thirteen have gone to scholars associated with the University of Chicago.

Although Chicago has long been the center of the study of free-market economics, Sowell was a Marxist in his twenties. He explained that, when working as a Western Union messenger after he left high school, he would sometimes ride the bus from the Wall Street area to his home in Harlem. The ride took him past the upscale department stores on Fifth Avenue, past Carnegie Hall, and through the affluent residential neighborhoods of Riverside Drive. "And then," Sowell wrote, "somewhere around 120th Street, it would cross a viaduct and onto 135th Street, where you have the tenements. And that's where I got off. The contrast between that and what I'd been seeing most of the trip really baffled me. And Marx seemed to explain it."

But then he took a summer job at the U.S. Department of Labor in 1960, when he turned thirty. Even after a year at the University of Chicago, including a course under Milton Friedman, Sowell had "remained as much a Marxist as I had been before arriving."

He spent the summer analyzing the sugar industry in Puerto Rico, where a minimum wage was set by the U.S. Government. It wasn't long before he noticed that as the minimum wage had risen, the number of sugar workers fell. He had always supported minimum wages, assuming they helped the poor earn a decent living. But now he realized that minimum-wage laws cost jobs and were a net detriment to the poor.

"From there on," Sowell wrote, "as I learned more and more from both experience and research, my adherence to the visions and doctrines of the left began to erode rapidly."

Soon, Sowell was "rethinking the whole notion of government as a potentially benevolent force in the economy and society." He also couldn't help noticing that his fellow bureaucrats did not care if the minimum wage helped workers. Their job was to enforce the laws. It was not to see if the laws did any good.

"It forced me to realize, Sowell wrote, "that government agencies have their own self-interest to look after, regardless of those for whom a program has been set up." Marxist theory ignores the powerful force of self-interest in the working of economies, and Sowell came to realize the centrality of self-interest to the human universe.

At Chicago, Sowell studied the history of ideas under the great Friedrich Hayek.

At Chicago, Sowell studied the history of ideas under the great Friedrich Hayek, but it was Hayek's own ideas that had lasting consequences for him. Hayek's essay "The Use of Knowledge in Society" dealt with how the information used to make economic decisions spreads through an economy. Its central insight is that knowledge is highly dispersed and no one person or group can possess all the knowledge needed to make good economic decisions. Therefore, he argued, the decision-making process should also be decentralized, the opposite of what Marx argued for.

Later, when Sowell was asked to teach a course on the Soviet economy, the significance of Hayek's essay hit home:

I could see what the factors were that led the Soviets to do what they were doing, and why it wasn't working. There was a knowledge problem that was inherent in that system. In a nutshell, those with the power didn't have the knowledge, and those with the knowledge didn't have the power.

Out of this came one of Sowell's most important books, Knowledge and Decisions (1980), which extended Hayek's work and, as Riley says, "would do so in ways that even Hayek had never contemplated."

In hopes of reaching a wider audience than Hayek, who wrote in the technical language of economics, Sowell's book, in "lieu of graphs and equations . . . offers rich metaphors and copious real-world examples that make the weightier concepts under discussion not merely digestible but tasty." This appeal to a wider audience is no small part of the reason that Sowell has been so influential.

Another is that, while an economist by training, Sowell's mastery of subjects is far wider. Gerald Early, of Washington University, noted that his expertise extends to sociology and history as well. "He had some kind of mastery of other fields to do the kind of comprehensive stuff he was doing. Whether you agree totally with his ideas or not, it was impressive what he was doing. Who knew an economist could write that stuff?"

Indeed, far too many economists can't write, period. Sowell most certainly can. Early, who is black himself, noted that "I knew lots of black people who were not academics and who had heard about him and were reading his stuff because it was accessible."

Another thing that distinguishes Sowell from all too many other economists is his insistence that theory be tested in the real world. Gunnar Myrdal, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1974, for instance, argued that third-world countries could not develop without extensive foreign aid and much central planning, despite the fact that post-war Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore did exactly that in the late twentieth century.

"I got no sense," Sowell wrote,

that Myrdal actually investigated these theories of his and compared them with anything that actually happened. I myself, of course, started out on the left and believed a lot of this stuff. The one thing that saved me was that I always thought facts mattered. And once you think that facts matter, then of course that's a very different ball game.

Myrdal and his type are essentially theoretical in their approach to economics. Sowell, like Stiller, Hayek, and Friedman, is empirical, demanding real-world proof, not just elegant ideas.

"The market can be ruthless in devaluing degrees that do not mean what they say."

Sowell has always regarded himself as fortunate that his higher education came before the era of affirmative action, which he regards as an unmitigated disaster for blacks. In his memoir, My Grandfather's Son (2007), the Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas recalled how shocked he had been when his law degree from Yale and his sterling grades failed to impress the white-shoe law firms where he applied for a job. "Now I knew what a law degree from Yale was worth when it bore the taint of racial preference," he wrote.

But Sowell had predicted this in the very first days of affirmative action. "The double standard of grades and degrees is an open secret on many college campuses, and it is only a matter of time before it is an open secret among employers as well," he predicted in 1970. "The market can be ruthless in devaluing degrees that do not mean what they say. It should be apparent to anyone not blinded by his own nobility that it also devalues the student in his own eyes."

One of Sowell's most important contributions has been to notice how wide the gap often is between ordinary black Americans and black intellectuals and civil rights leaders. In a pair of op-eds in The Washington Post in 1981, Sowell wrote that

Historically, the black elite has been preoccupied with symbolism rather than pragmatism. Like other human beings, they have been able to rationalize their special perspective and self-interest as a general good. Much of their demand for removing racial barriers was a demand that they be allowed to join the white elite and escape the black masses.

In other words, they have been all too anxious to do what Sowell had spurned doing many years before at Harvard.

In fact, Sowell doesn't have much use for the pretensions of intellectuals of whatever color. Perhaps my favorite quote in Maverick is used by Riley to open his chapter on "Sowell's Wisdom": "Some of the biggest cases of mistaken identity are among intellectuals who have trouble remembering that they are not God."

In this short, well-written book, Jason Riley leads the reader on an enlightening tour of the thought and experiences of one of the most luminous minds this country has produced.

It should cause many readers to explore the works of Thomas Sowell. They will be richly rewarded for doing so.

1 Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell. (Book Review by Jason Riley.)

Basic Books, 304 pages