'The Columnist' Review: Master of the Merry-Go-Round

By: Fergus M. Bordewich (WSJ)

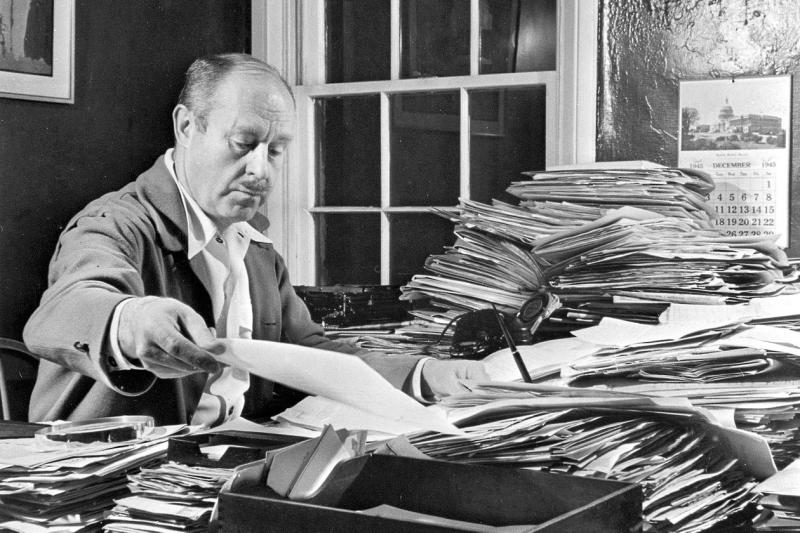

For almost 40 years, there was no more widely read, and perhaps no more widely hated, journalist in America than the ferociously independent syndicated columnist Drew Pearson. In a career that spanned every presidential administration from Hoover to Nixon, Pearson prowled the corridors of government, embarrassed the powerful, savaged the venal, fought secrecy, exposed blunders, and—not least—entertained and offended the public.

In "The Columnist," an engrossing and revealing biography of Pearson, Donald A. Ritchie sums up Pearson's storied career by tracking the acute displeasure he provoked: "Herbert Hoover tried to have him fired. Franklin Roosevelt called him a chronic liar. Harry Truman sent the FBI to investigate him. Dwight Eisenhower ostensibly ignored him while having his press secretary trash him. John Kennedy griped that the powers of the presidency gave him no influence over the columnist. Lyndon Johnson did his best to co-opt him. Richard Nixon put him at the top of his enemies list."

Mr. Ritchie, a former historian of the U.S. Senate, is the author of several previous books, including "Press Gallery," a history of Washington journalism in the Civil War era, and "Electing FDR," a chronicle of the 1932 campaign. As Pearson's biographer, he is judicious if mostly friendly. Along with delivering a richly anecdotal account of the life, he offers up a crowded playbill of insider Washington dramas. Pearson comes vividly alive as an opinionated man of intense moral force, entrepreneurial energy and sometimes questionable judgment. Mr. Ritchie's research is impressive, drawing on Pearson's private diaries and personal correspondence, copious public writings, and thousands of pages of files collected by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI.

Drew Pearson was born in 1897 into a "thee-ing" and "thy-ing" Quaker family in Illinois. He trapped skunks as a boy and in his teens served as an advance man and tent-pitcher for traveling Chautauqua gatherings. Having acquired a strong sense of moral indignation, an education at Swarthmore, urbane manners and a lust for travel, he established himself as a one-man newspaper syndicate and worked his way across the Pacific as a deckhand in order to freelance in the Far East, where, barely into his 20s, he talked his way into an interview with Mahatma Gandhi. On his way home through Europe, he snagged another with Benito Mussolini. A few years later, he gained entree to Washington society by marrying the daughter of Eleanor "Cissy" Patterson, the city's wealthiest woman and the owner of the influential Washington Times-Herald.

In 1932, Pearson and his then-partner Robert Allen created Washington Merry-Go-Round, the daily column that for generations was every morning's must-read for the capital's movers and shakers. Pearson later added a newsletter, a weekly radio broadcast and eventually a television program. (Allen left the column during World War II but contributed occasionally thereafter.) At its peak, Washington Merry-Go-Round, always Pearson's flagship, appeared in more than 600 papers, while his radio show reached some 20 million listeners on 250 stations. By the early 1940s, Pearson was earning at least $75,000 a year at a time when members of Congress were paid just $10,000.

Pearson’s formula for success was what the Saturday Evening Post called “aggressive indiscretion”: hooking readers with the promise of insider revelations and tales of conflict at the highest levels of government. Pearson told his staff that when people in power betrayed their trust, “then it is your job to be ruthless in exposing that betrayal. You must be their watchdog. You must let them know what the publicity penalty is—if they fail.” Writes Mr. Ritchie: “He had a knack for making enemies, preferably those with big names, who kept him at the center of public controversies. He could also invest trivial matters with urgency and present gossip as established fact.”

In contrast to his contemporary Walter Lippmann, Pearson was less an analyst or pundit than a bulldog reporter. He relied on his own connections as well as on a team of enterprising leg-men, a vast network of sources, and leakers planted in virtually every federal agency, the White House, Congress and the military. Roosevelt’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull once opened a staff meeting by asking: “Are we talking for this room or for Pearson?”

A 1944 poll of the Washington press corps rated Pearson (and not Lippmann) as the columnist who exerted the greatest influence over national opinion. But when it came to reliability and fairness, he received hardly any votes. “Though Pearson aimed for the truth,” Mr. Ritchie writes, “the pressure of daily deadlines meant sometimes settling for less than the whole truth.” Pearson was sued for libel more than any other journalist, and proud of it. He was sometimes compelled to print a retraction because he failed to substantiate a claim. During the Truman administration, in a rare defeat, he was successfully sued by a high-powered lobbyist whom Pearson accused of serving as an agent for the Polish Embassy and assisting the escape of a Communist spy from the United States.

Although a registered Republican for most of his life, Pearson was a staunch supporter of the New Deal and its liberal principles. Roosevelt and his cabinet members, Mr. Ritchie says, “showered” him with leaks to “test the waters for public and congressional reactions before making official announcements.” He nevertheless exposed inept appointees, attacked programs that misspent public funds and incurred FDR’s wrath by referring to the president’s children as “spoiled brats.” During the war, Roosevelt publicly called him a liar for jeopardizing the wartime alliance by—accurately—reporting on anti-Russian sentiments in the State Department.

Pearson’s relationships with public figures often resembled a pas de deux of mutual exploitation. J. Edgar Hoover was a case in point. In the 1930s, Pearson helped craft Hoover’s reputation by lavishing praise on the FBI chief, whom he dubbed “Super-G-Man.” In return, he received a generous flow of tips from the agency. Later, as Hoover’s power swelled unchecked, Pearson regretted that he had helped to “create a monster,” as he put it. Hoover put agents on his trail and tapped his phones in an effort to expose his sources.

Pearson’s relationship with Sen. Joe McCarthy was similarly symbiotic. The columnist initially found McCarthy smart and likable and admired his work on behalf of slum clearance and humanitarian relief in postwar Europe, and the junior senator from Wisconsin proved to be a helpful source on Capitol Hill. But Pearson became disgusted by McCarthy’s wild attacks on innocent public officials and systematically refuted them in his column, inadvertently contributing to the senator’s emergence as the nation’s leading anticommunist by calling attention to McCarthy’s demagogic crusade.

When leg-man Jack Anderson protested that McCarthy had been useful to the column, Pearson replied: “He may be a good source, Jack, but he’s a bad man.” McCarthy retaliated by branding Pearson “a sugar-coated voice of Russia” and a “Moscow-directed character assassin” and even physically assaulted him at a Washington club. Although Pearson had been the first journalist to expose a major Soviet spy ring based in Canada, and had tipped off the State Department about Alger Hiss’s Russian connections before anyone else, McCarthy’s smears caused him the loss of his main radio and TV sponsors, and a significant number of newspapers dropped his column.

Pearson was willing to withhold stories when he felt they truly jeopardized national security, and he almost never even hinted at a politician’s sexual improprieties. Virtually everything else was fair game. He chastised Douglas MacArthur for driving impoverished Bonus Marchers out of Washington at bayonet point in the early 1930s; flayed Spanish militarist Francisco Franco during that country’s civil war; broke the story of Gen. George S. Patton’s scandalous slapping of shell-shocked soldiers in 1943; and hounded Dwight Eisenhower’s bribe-taking chief of staff, Sherman Adams, until he resigned.

Although never close to the Kennedys, Pearson remained a force to be reckoned with throughout the 1960s. He had long admired Lyndon Johnson, tagging him as early as 1940 as a rising star. When LBJ became president, Pearson applauded his administration’s anti-poverty programs, which promised to carry on the spirit of the New Deal. He occasionally even wrote speeches for the president. He stood with Johnson on the bombing of North Vietnam but finally broke with him over the war in 1968. Pearson’s relations with Richard Nixon had been frosty since Nixon’s Red-baiting days in the early 1950s and didn’t improve when Nixon entered the White House. But by the late 1960s, Pearson had handed over much of the responsibility for Washington Merry-Go-Round to Jack Anderson, his hand-picked successor. Even so, he was still working at a daunting pace when he suddenly died from the effects of a heart attack in September 1969, age 71.

The press has radically changed since Pearson’s day. Today no reporter possesses anything like the personal power or notoriety that Pearson flaunted. Transparency laws and the internet have vastly multiplied the sources of information available to both journalists and ordinary citizens. What was “once available almost exclusively to columnists and commentators,” Mr. Ritchie notes, is now, potentially, available to all.

“The decades after Drew Pearson’s death saw storehouses of government documents, intelligence reports, personal manuscripts, and once-secret recordings opened for research,” Mr. Ritchie writes. It now became possible to assess both the assertions that appeared in Washington Merry-Go-Round and the accusations of dishonesty and bias leveled against Pearson himself. Targets high and low repeatedly denounced Pearson as a liar, “but the subsequent archival evidence more often verified his accusations than the protests of his accusers, and validated Drew Pearson’s sense of smell.”

In the end, Mr. Ritchie persuasively concludes, despite Pearson’s occasional mistakes, “the evidence affirms his claim that he performed a public service by revealing how politicians and government really worked.” It is still a public service that journalists today perform, though few can match Pearson’s astonishing energy and relentless sense of mission.

—Mr. Bordewich’s most recent book is “Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America.”

There is nobody in the media today with such influence.

The Book is:

THE COLUMNIST

By Donald A. Ritchie

Oxford, 367 pages