'The Reason for the Darkness of the Night' Review: Poe's Eureka Moment

By: Jeremy McCarter (WSJ)

Viewers of "The Good Place," the TV comedy series and ersatz philosophy seminar, learned in an early episode that the prophets of the world's major religions have figured out only 5% of the mysteries of the cosmos. But (according to the show) one night in 1972, a visionary thinker offered an explanation that was an astonishing 92% right. The joke is that this all-seeing genius was a Canadian stoner kid named Doug Forcett, who solved the riddles of existence while stupendously high.

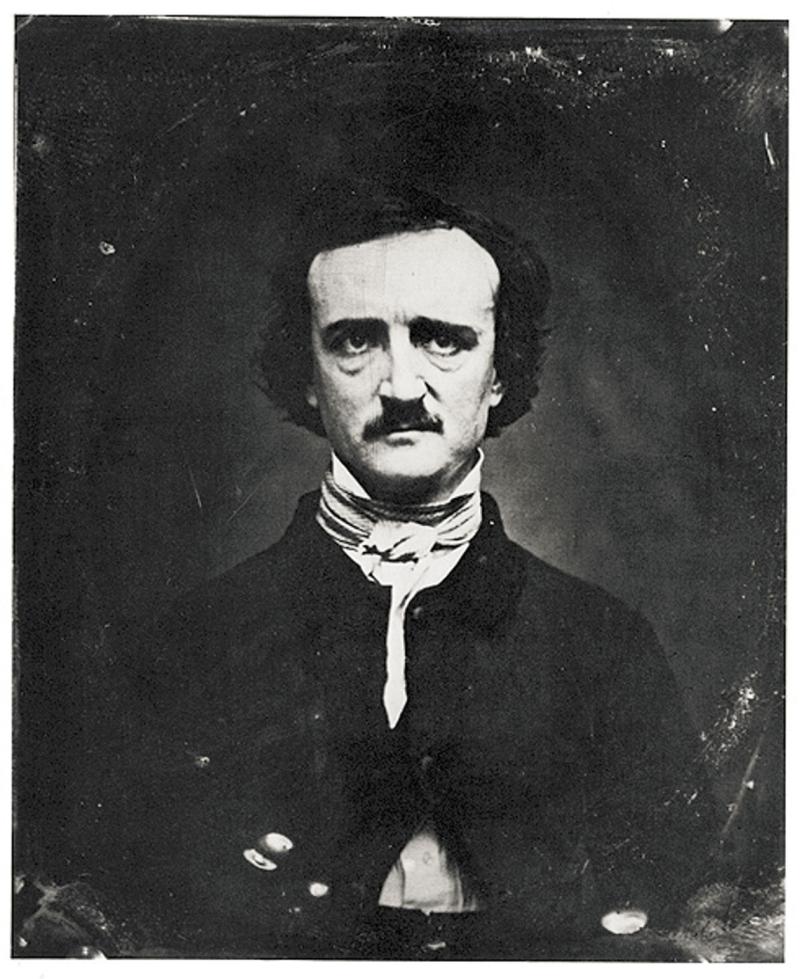

Could the history of science offer a real-world analog for Doug's achievement? In an 1848 lecture, Edgar Allan Poe—the "Raven" guy, the progenitor of detective stories and spooky science fiction, who married his 13-year-old cousin, and died after being found insensibly drunk and wearing (somehow the most unsettling detail of all) another man's clothes—this ink-stained wretch described a startling number of what would turn out to be prominent features of modern cosmology, including the big bang, the big crunch and the unity of space-time. It took scientists decades to catch up to him. And who knows? They might still be catching up even now.

In "The Reason for the Darkness of the Night," John Tresch resists the urge to tell this unlikely story in a fusillade of capital letters and exclamation points. Where Poe sent audiences winging around the universe (or multiverse, another concept he seems to have anticipated), Mr. Tresch keeps to a steady course. He approaches Poe's uncanny lecture—and its published version, the prose poem "Eureka"—not as a crazy fever dream, but as an inspired series of leaps from a firm grounding in fact. T.S. Eliot, speaking for generations of skeptics, dismissed "Eureka" because of Poe's "lack of qualification in philosophy, theology, or natural science." On the contrary, Mr. Tresch argues, Poe "was positioned as well as nearly any of his contemporaries to speak on cosmology." He makes his case by telling Poe's entire life story, endeavoring to show that "Eureka" was the culmination of decades spent engaging with the leading scientific thought of the time. It's like watching Doug Forcett pore over Kierkegaard between bong hits.

To the extent that Poe's cosmic vision made him a prophet, he was one without honor, if "honor" is understood to mean "money." His lecture was intended as the kickoff of a speaking tour, the goal of which was—as ever—to shore up his finances and to line up backing for a new magazine. The buzz was loud, the advance notices prodigious. One newspaper in New York, where the lecture would be held, hailed Poe as "not merely a man of science—not merely a poet—not merely a man of letters. He is all combined; and perhaps he is something more." Poe himself told friends that he was about to "revolutionize the world of Physical & Metaphysical Science." ("I say this calmly," he added, "but I say it.")

Then it snowed on the night of the gig and almost nobody came.

If you were one of the hardy few in the New York Society Library audience, you would have seen a galvanizing performance, which was de rigueur for lectures in those days. Mr. Tresch’s book places Poe in the unruly world of 1840s America, where there was no clear demarcation between the quackery of P.T. Barnum and a serious presentation by a scientist, a term that had been coined only 15 years earlier. Poe himself spent his career zigzagging between respectability and deceit. He’d received engineering training at West Point, and scratched out his living by reviewing new books on science, so he could spot a fraud when he saw one. (Of all the weird bits of Poe trivia, here’s the weirdest: His bestselling book in his lifetime was a textbook on conchology—the classification of shells.) But as a writer of fiction, he wasn’t above a little hoaxing of his own. He added enough scientific gilding to some of his tales to make readers think they might be true.

In his lecture on the universe, Poe turned this method upside down: Here he used fiction in the service of science. He began by citing a letter, purportedly written in 2848, that mocked the primitive methods of 1848, when overconfident scientists believed that deduction and induction were the only paths to knowledge. Intuitive leaps, Poe insisted, could yield insights of their own. One such “soul-reverie” led him to argue that the universe began when “a primordial Particle” erupted outward in every direction. Everything that has happened since then is the result of the interplay of “the two Principles Proper, Attraction and Repulsion.” So far, so reasonable, by the lights of 21st-century cosmology. Still, plenty of what Poe went on to assert is either flatly wrong, ludicrously wrong, or outside the realm of cosmology properly defined, e.g., his suggestion that if there are multiple universes, each might have its own god.

“The Raven,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Pit and the Pendulum”: As far as Poe was concerned, these gloomy triumphs of his imagination—all the poems and short stories that have made him immortal—counted for less than his cosmic speculations, which he considered the pinnacle of his career. “I could accomplish nothing more since I have written Eureka,” he told his mother-in-law/aunt. So imagine his dismay when, after requesting a print run of 50,000 copies, his publisher granted him only 500, and even these didn’t sell. A year later, Poe would spend a calamitous day and night in Baltimore, drinking himself to oblivion. He died at 40.

Had he lived, he would have found it ever more difficult to “revolutionize the world of Physical & Metaphysical Science.” Mr. Tresch, who teaches at the Warburg Institute at the University of London and has previously written about Romanticism and science in 19th-century France, shows that the last years of Poe’s life coincided with increased regimentation in American thought. New organizations such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science began applying rigorous standards to scientific discourse. “Eureka” was “precisely the kind of publicly oriented, freewheeling, generalizing, idiosyncratic, and unlicensed speculation that the AAAS was created to exclude,” he writes.

Mr. Tresch’s attempt to reach beyond biography and enfold the complexity of an era is ambitious, sometimes overly so. The narrative tends to lose its way during side trips to describe Poe’s contemporaries; at times, it seems a reach to interpret Poe’s fiction in light of his interest in science. (It makes you think even more highly of “The Age of Wonder,” Richard Holmes’s dazzling synthesis of science, Romantic poetry and British history.) So it’s surprising to close this book and still feel saddened by the story it tells, about the recurring sorrows of Poe’s often nightmarish existence.

Poe drafted “Eureka” in a year of profound grief: His cousin Virginia was scandalously young when he married her and nearly as young when tuberculosis killed her. Her death at 24 adds to the evidence that the forces of the universe (or multiverse, if you please) conspired against him. Yet Poe himself shares the blame for his misfortunes, giving in again and again to what Mr. Tresch calls his “irrational, seemingly unstoppable impulse to set his life on fire.” If Poe invites an unflattering comparison to a teenaged shroom enthusiast on a TV comedy, it’s not least because he apparently entrusted his literary remains to a bitter rival, Rufus Griswold, who had far more success in soiling his reputation than Poe ever did in building it.

Even now, two centuries after “Eureka,” any judgment of Poe’s visions should be a little tentative: There’s so much we still don’t know about how the cosmos works. (Just last month, a new attempt to map the universe suggested that Einstein’s general theory of relativity might be wrong.) Whatever the ultimate merits of his cosmology turn out to be, you have to admire his epistemology and the dogged way he pursued it. Intuition really did furnish valuable insights. Mr. Tresch derives the title of his book from Poe’s surest basis for scientific acclaim: He is widely acknowledged as the first to solve Olbers’s paradox. (If the heavens are limitless, with stars in every direction, how can the sky be dark at night? Because the universe must be finite in both space and time, Poe surmised.)

In the end, the fictional character Poe most resembles is one of his own creations: the unfailing detective C. Auguste Dupin, who scoffed at the methods of the authorities, trusted his own hunches, and felt certain that if solving a problem required reflection, “we shall examine it to better purpose in the dark.”

—Mr. McCarter is the co-author, with Lin-Manuel Miranda and Quiara Alegría Hudes, of the forthcoming “In the Heights: Finding Home.”

Do we need another Poe biography?

He was one of the greatest prose stylists in the English language.

As far as intuition is concerned, I think we have seen some who have been very good at it in the past 5 years.

The Book is

THE REASON FOR THE DARKNESS OF THE NIGHT

By John Tresch

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 434 pages

12358W