'Ding Dong! Avon Calling!' Review: Opening Doors for Women

By: Ellen Wayland-Smith (WSJ)

In the 1880s, David H. McConnell was working as a door-to-door book salesman when he had a novel idea. He noticed that the housewives he cold-called, while seldom interested in buying his encyclopedias, were thrilled with the complimentary perfume samples he offered. What if he were to jettison books for cosmetics, recruit a nationwide sales corps of housewives, and then capitalize on their local social circles to move his merchandise?

It was a risky proposition. America's once-local economy was undergoing seismic shifts at the dawn of corporate capitalism. As national production and distribution became increasingly centralized, the role of the traveling salesman, and the idea that selling was exclusively a man's job, appeared inefficient relics of the old system. The Victorian ideal of women as domestic "angels in the house," free of the moral taint of a rough-and-tumble masculine marketplace, still held sway. Still, McConnell sensed in the housewives he met both a desire for novelty and a previously untapped part-time labor market. He put his idea to the test, and the Avon corporation was born.

In "Ding Dong! Avon Calling!" Katina Manko offers an in-depth study of the Avon corporation from its founding as the California Perfume Co. in 1892 through Avon's dissolution in 2016. Its conception was unique: in order to sell products, the company had first to "sell" itself as an exciting business opportunity to the women who would single-handedly do its on-the-ground product promotion and distribution. The book explores how McConnell's dependence upon a solely female sales force led to the evolution of a distinctive, woman-centered corporate culture—and illuminates how American business has evolved in response to shifting gender roles.

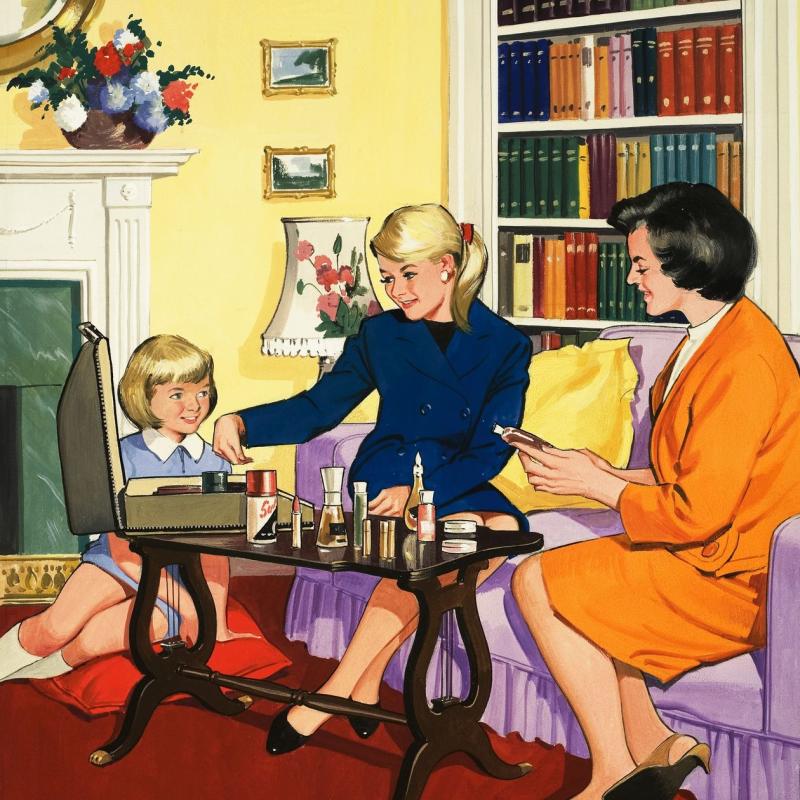

Key to California Perfume's initial success (the New York-based company would re-brand itself Avon in 1939) was convincing women—and their husbands—that sales was a respectable occupation. The stigma of commerce was lifted in part by a sense of intimacy; prospective sellers were encouraged to get their family, friends and even churches involved in the project. Thus framed, selling resembled a feminine "social call" more than a masculine hard sell. Avon recruitment literature walked a fine line between calling on women to become entrepreneurs and assuring them they would still be able to keep up their domestic duties, promising each prospective Avon lady a role designed "neither to interfere with her primary duties (caring for her home and family) nor subordinate them."

To recruit sellers, Avon sent out an all-female corps of traveling agents, each assigned a "territory" of four to six states, who acted as intermediaries between the territory's sales force and New York executives. When the corporation began to branch out into urban areas in 1935, those women who had distinguished themselves as "general agents" were tapped to head regional sales offices. The development of this female managerial class, endowed with then-unusual autonomy, built a ladder that a local contract worker might climb. And this design proved lucrative: Between 1940 and 1953, the firm's sales force grew from 26,000 to 125,000, and its annual sales figures more than quintupled.

A unique feature of Avon’s managerial strategy was its reliance on “motivational” literature to build esprit de corps in a sales force that otherwise had no contact with other agents, or with the home office. Avon ladies were legally defined as contract workers; they bought products directly from the company, and received a commission of 30-40% on each product sold. Company literature advertised this arrangement as bold entrepreneurship. “Now You Are In Business for Yourself” beamed one promotional pamphlet from the 1920s. “Out to Win!” announced a print ad from 1954, featuring a nattily dressed woman standing at the corner of “Prize Avenue” and “Earning Street.”

Avon promised that a career in direct selling would give women the power to create their own wealth, blending what Ms. Manko calls “an individual self-help, ‘Horatia Alger’ celebration with an ironic anti-corporate defense of proprietary capitalism.” Yet the average Avon Lady’s take by the 1950s fell far short of the corporation’s official rhetoric. “In truth,” the author reveals, “an average representative’s annual sales”—approximately $450, or just over $4,500 today—“was barely half of the lowest earnings projection in the recruiting manual.” In this, Avon was in line with standard recruitment strategies of the era, which continued to vaunt the ideal of an “independent,” capital-owning employee long after the economic conditions fostering this ideal had disappeared.

This is a book born in the archives, and Ms. Manko is meticulous in mining the rich trove of Avon material that, as an independent scholar, she helped to catalogue for the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Del. In excavating Avon’s history, the author presents a complex weave of documentary evidence, from executive meeting notes to internal newsletters to saleswomen’s private notebooks. At its best, the candid, day-to-day ordinariness of the material offers an intimate glimpse into a bygone era. At times, though, the pages brim with such a profusion of facts and figures that a larger narrative recedes from view.

Times have changed: Avon executives never expected sales associates to make a living selling their products, for the simple reason that most were already “employed” as unpaid homemakers. Women in the workplace today enjoy a degree of financial independence that Avon’s early saleswomen could only dream of. Yet American women continue to shoulder the bulk of unpaid home labor, 4 hours a day to a man’s 2.5. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the shockingly disproportionate rate at which women lost their jobs or had to leave them when childcare vanished is a grim reminder of how tenuous working women’s “independence” remains. Ms. Manko’s book serves as a timely warning from the past, urging us to do better in the present.

Ms. Wayland-Smith is the author, most recently, of “The Angel in the Marketplace: Adwoman Jean Wade Rindlaub and the Selling of America.”