'Burning Man' Review: Extremely D.H. Lawrence

By: WSJ

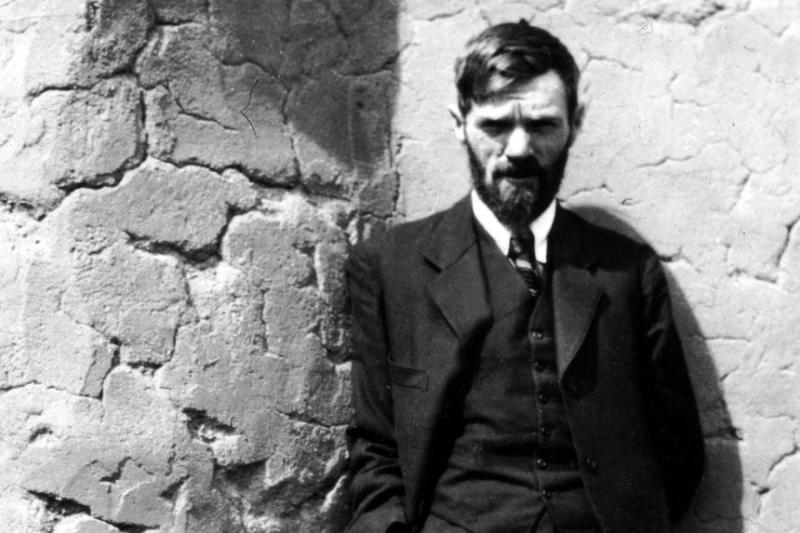

Of all the countless anecdotes told of D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930), my absolute favorite takes in the musician-cum-critic Cecil Gray, Lawrence's neighbor during his World War I-era sojourn in Cornwall. The story goes that Gray, hard at work one morning in his remote cottage, heard a knock at the door. It opened to reveal the author of "The Rainbow"—bearded, beady-eyed and intent—who without preamble demanded: "How long is it, Gray, since you have loved me?" What Gray is supposed to have said in return is not recorded; shortly afterward Lawrence could be seen making his way back over the fields to the house he shared with his recently acquired wife, the former Frieda von Richthofen.

There is, you suspect, quite a lot going on here, not least the question of Lawrence's supposed, or half-suppressed, or perhaps only obliquely acknowledged homosexuality. But the most striking element is the whiff of emotional absolutism.

Lawrence has decided for Gray that Gray is in love with him; what Gray thinks is immaterial; the matter is settled for him on the spot. At the same time, there comes floating over the proceedings a modest hint of determinism—the thought that, at any rate from Lawrence's angle, this had to happen, that powerful natural forces have targeted this particular part of western England with the sole aim of bringing Lawrence and Gray together. Resistance is futile.

One of Frances Wilson's key themes in "Burning Man" (FSG, 488 pages, $35), an ambitious biography, is the extremism that Lawrence brought to every relationship, transaction and even conversation into which he ever entered. Women tended to bear the brunt of this overblown spiritual gigantism—the source of the terrific feminist assault on him that began in the late 1960s—but men were just as vulnerable to attack. To engage with Lawrence, or to be engaged by him, was instantly to be drawn into a game in which he established the rules, more or less as he went along, changed them whenever it suited him, held all the cards and wasn't above cheating if he thought that the situation demanded it.

All this was bound to cause trouble, and one of the most common sights in "Burning Man" is the spectacular falling-out. The devoted acolyte whom Lawrence ends up spurning; the intense, passionate companion who fails to stay the course because he or she is, well, a bit less passionate and intense than the object of their admiration: All this is to Lawrence what daffodils were to Wordsworth, his emotional meat and drink, the force that drove him. In Ms. Wilson's account, the Cornish interlude comes littered with high-grade casualties—the critic John Middleton Murry, the writer Katherine Mansfield, the hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell—who found the going too tough to be borne. In a literary world characterized by warring armies and endless factional fighting, Lawrence was a procession of one, "the sole member of his own party" as his biographer neatly puts it.

It is to the author’s great credit, then, that hardly any of the vast pile of dirt that has accumulated around Lawrence in the 90-odd years since his death is swept under the carpet. Ms. Wilson, who has written biographies of Thomas De Quincey and Dorothy Wordsworth, knows that D.H. Lawrence’s reputation has been in the doldrums for nearly half a century; that feminists loathe his phallocentric view of the world; that his sulks, sneers and general intransigence would disgrace a child of 5; and that to deny any of this would be a calamitous mistake. Significantly, some of the worst put-downs of Lawrence are filed by mild-mannered quietists. E.M. Forster, accused by Lawrence of ignoring his “own basic, primal being,” complained that he liked “the Lawrence who talks to Hilda [the maid] and sees birds and is physically restful and wrote The White Peacock [Lawrence’s first novel, published in 1911] . . . but I do not like the deaf impercipient fanatic who has nosed over his own little sexual round until he believes that there is no other path for others to take.”

If there was faint mitigation, it lay in the social distance traveled. Lawrence was a coal miner’s son from rural Nottinghamshire, which mattered in early-20th-century England. His climb to the literary reviews and the drawing rooms of Bloomsbury left him out on a limb, halfway between one class and another, and liable to be condescended to by both. Nurtured and indulged by his aspirational mother, he looked down on his collier father as a pit-head Caliban, only to reverse the roles in middle age and take refuge in Lawrence senior’s manliness. A bleak little poem called “The Saddest Day” captures the author’s ascent into the artistic middle classes in half-a-dozen horribly wistful lines:

O I was born low and inferior

But shining up beyond

I saw the whole superior

world shine like the promised land.

So up I started climbing

to join the folks on high,

but when at last I got there

I had to sit down and cry.

The religious framing of “promised lands” and “folks on high,” with its hint that the class structure has a spiritual dimension, is important. As for the condescension, the novelist David Garnett, a member of the Bloomsbury group, once declared that Lawrence was “the weedy runt you find in every gang of workmen, the one who keeps the other men laughing all the time, who makes trouble with the boss and is saucy to the foreman, who gets the sack, who is ‘victimised’ . . .”

Lawrence is certainly the victim in “Burning Man,” as well as being its hero and also, you infer, its agent provocateur, setting up situations in which he could appear to advantage, turning his marriage to Frieda—quickly detached from a college professor named Ernest Weekley and her three small children—into a continuous piece of amateur dramatics. Ms. Wilson is good on the self-consciously performative aspects of the Lawrences’ union, the plates flung to and fro across dinner tables for the benefit of their guests and the satisfaction Frieda seems to have derived from being beaten up by her other half. The sense of someone who at all times seemed bent on stage-managing his life for the delectation of an admiring audience is sometimes a bit too strong for comfort.

Far from being a conventional life and times, “Burning Man” is a triptych based on a Dante-esque pattern, full of highly imaginative detours into Lawrentian dualism and Lawrentian paradox. “Hell” is England during World War I, where the authorities suspected the Lawrences of pro-German sympathies (Frieda was related to the Prussian air ace Manfred von Richthofen); “Purgatory” is time spent in postwar Italy with his fellow writers Norman Douglas and Maurice Magnus; “Paradise” is his three-year stint in New Mexico, at which point the creative jag that had seen him through “Aaron’s Rod” (1922), “Fantasia of the Unconscious” (1922) and “Studies in Classic American Literature” (1923) began to be jeopardized by his tubercular lungs.

At this point, rattling around southern America with Frieda, his benefactress Mabel Dodge Luhan and their mutual friend Dorothy Brett, the real impact of Lawrence’s dual nature starts to reveal itself. “The landscapes that Lawrence inhabited always also inhabited him,” Ms. Wilson shrewdly notes, and yet these were short-term fixes: The adult Lawrence was a wanderer, a kind of eternal vagrant, restless wherever he set up camp, who once wrote that he truly wished “I were a fox or a bird—but my ideal now is to have a caravan and a horse, and to move on forever.” To edge even nearer to the world of the novels, “Women in Love” (1920) and “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” (1928) are about physicality, impulse and mighty currents suddenly erupting into dead air, but Lawrence turns out to have had a horror of being touched. Had Cecil Gray reached out to embrace him, you suspect, something much worse than a dinner plate would have been hurled back.

Clearly there were two Lawrences: Forster’s nice man who talked to the maidservant, and the ranting phallocrat; the poet of rootedness and the wandering gypsy. “God save us, what a business it is even to be acquainted with another creature,” the pre-purgatorial Lawrence once declared. And this is part of the problem, both for Lawrence himself and the biographical sleuths bent on capturing his essence. He would have been a happier man if he could have simply calmed down and convinced himself that not all of life consists of struggles to the death on symbol-strewn battlegrounds. On the other hand, denying this would have meant denying a substantial part of who he was.

Much of “Lady Chatterley” now seems faintly hilarious. Yet this is not to gainsay the absolute seriousness with which Lawrence went about writing it or the suspicion that Lawrence’s old-world puritanism would never quite be vanquished by his epic descriptions of physical love.

Meanwhile, the charivari goes on, an endless whirligig of rows and separations, high-energy compositional bouts (the first version of “Lady Chatterley” was written in a few weeks) and mounting evidence of physical decline. Like Lawrence’s homosexuality, his TB was a topic that he shied away from addressing; as late as the mid-1920s, he was still insisting that his troubles were merely “bronchial.” When Frieda, seeing him cough blood into a handkerchief, decided to call a doctor, he threw an iron eggcup at her. Curiously, only at these moments of maximal intensity do you begin to distrust the assembled cast’s habit of taking Lawrence and everyone around him at face value.

Take, for example, a scene from the World War I era, written up many years later by the Imagist poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) in “Bid Me to Love.” She and Lawrence are interrupted by the arrival of Frieda and her friend Dorothy Yorke. Afternoon tea in a country cottage? No indeed, for H.D., as Ms. Wilson puts it, sees “a mask where his face had been.” Lawrence has turned into a satyr, whereas H.D., the author helpfully glosses, has returned to Hades and is back in the role of Eurydice, while also reconstructing the scene in “Women in Love” in which Hermione, pulled by some magnetic force, picks up the lapis lazuli and makes her way over to Birkin. All the same, the willed significance that hangs over so many aspects of Lawrence’s life, the feeling that every half-eaten sandwich has some huge symbolical import and that God, Nietzsche and the devil lurk behind every shop front, is, in the end, what makes him the figure he is.

In this context, there is something rather satisfying about the final conundrum that Frances Wilson sets out to solve. This is the question of what, after his death at Vence in the hills above Nice, happened to his ashes. Ms. Wilson reckons they were taken back to New Mexico and eaten by mesdames Brett, Dodge Luhan and his widow. But, then, Lawrence had spent a lifetime consuming the people around him. They could have been forgiven for getting a little of their own back.

—Mr. Taylor is the author, most recently, of “The Lost Girls: Love and Literature in Wartime London.”

D H Lawrence

English Writer & Poet, who concerned himself with the effects of modern life and industrialisation.

The Book is:

Burning Man: The Trials of D.H. Lawrence