‘Capote’s Women’ Review: Betrayal of the Swans

By: By Moira Hodgson

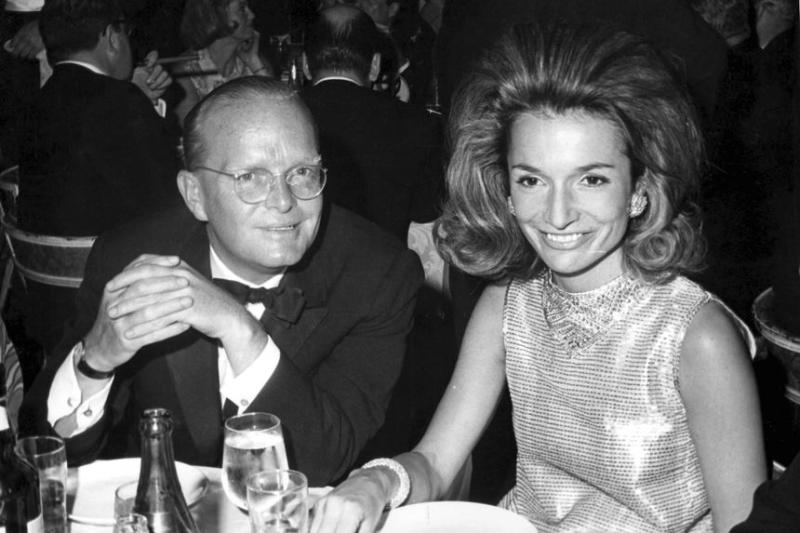

In November 1975, Truman Capote published “La Côte Basque, 1965,” a chapter from a novel he was writing called “Answered Prayers.” The book, acquired by Random House nine years earlier, was to be Capote’s magnum opus, as he put it, an intimate exposé of midcentury New York society that would place him alongside Marcel Proust and Edith Wharton. After the success of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1958) and his masterpiece, “In Cold Blood” (1966), Capote had shown himself to be a virtuoso in both fiction and nonfiction. His eagerly awaited new work would be a combination of the two. The book was so long in coming, however, that people began to wonder if the 51-year-old author was writing it at all.

When “La Côte Basque, 1965” appeared in Esquire magazine it proved to be thinly fictionalized, salacious gossip about the small circle of rich society women who were Capote’s friends. He’d been warned that they’d recognize themselves. “Naaaah, they’re too dumb,” Capote said. “They won’t know who they are.” He could not have been more wrong.

Laurence Leamer, a prolific biographer (“The Kennedy Women,” 1994), deftly tells the stories of the stylish, glamorous women whose trust Capote cultivated and then betrayed. Impish, flamboyantly gay, a good listener and a witty raconteur, Capote shone in their company. He came from a small town in Alabama but with his charm and sharp intelligence managed to ingratiate himself into the highest echelons of New York café society. The tiny, golden-haired writer with a squeaky boy’s voice presented no threat to the men. The women adored him. His intimates included Babe Paley, Nancy “Slim” Keith, Lee Radziwill (sister of Jackie Onassis), Pamela Churchill, the Boston Brahmin C.Z. Guest, Marella Agnelli (a princess married to the head of Fiat) and Gloria Guinness, who was determined, Mr. Leamer tells us, “to sit atop the swirling social world” and spent $1.5 million a year on clothes. Capote called these women his “swans.”

“Truman intended to rip open the lives of [these] people . . . exposing whatever darkness he found,” writes Mr. Leamer. “In the meantime, he would accept their hospitality and, with his almost photographic memory, store away everything he learned.” As he’d done with “In Cold Blood,” he envisioned writing something brilliant, entirely novel and unexpected.

As he talked to the women over the years, exchanging deep confidences, “Truman seemed to be exposing his most private secrets, but he was playing one of his most astute psychological games. These intimacies were valuable commodities that he used to then draw out the secrets of his listener.”

If the swans were horrified by what they read in “La Côte Basque, 1965,” they’d probably have been less than thrilled by the revelations in Mr. Leamer’s profiles. The women, he tells us, were obsessed with the idea of marrying rich, powerful men, but at the same time they had a pretty low opinion of the opposite sex. Not one of them was happy with her husband.

“La Côte Basque, 1965” takes its name from the venerable French restaurant on East 55th Street (now, sadly, closed). At luncheon over flutes of Roederer Cristal champagne, “Lady Ina Coolbirth,” left by her latest husband, a boring English lord, delivers an increasingly sodden litany of outrageous tales about those in the dining room and beyond, some under their real names. When Slim Keith read the story, she realized to her horror that the character was based on her.

The woman who was perhaps the most hurt by Capote’s betrayal was his favorite, the “impenetrably cool” Babe Paley, who was miserably married to William Paley, the chairman of CBS and a shameless serial philanderer. She had told Truman everything. “Here was this woman,” Mr. Leamer observes, “envied beyond measure for her perfect life, when Truman was the only one who saw that her existence was a tragedy.” As a result of a car accident Babe had plastic surgery and wore false teeth. She was a prisoner, spurned by her husband and terrified of him. The Paleys had been remarkably generous to Capote, flying him around the world and introducing him into the most elite circles. But he thought nothing of exposing them in his story. Babe Paley never spoke to him again.

Mr. Leamer reports that Pamela Digby Churchill—the wife of Randolph Churchill, alcoholic son of Winston—“appraised men the way a gemologist evaluated diamonds, making a close examination to determine its precise worth.” She poached Slim Keith’s second husband, the producer Leland Hayward. When Keith, distraught, returned to her house in Manhasset, N.Y., Churchill had already been there, placing red stickers on the furniture she wanted to keep in the divorce. Reading this, I couldn’t help thinking of Alexander Pope’s epigram, “We may see the small value God has for riches by the people he gives them to.”

“As much as Truman was drawn to the beauty, taste, and manners in that world of privilege, he was repulsed by its arrogant sense of superiority and ignorance of life as most people lived it.” Mr. Leamer writes. “Life had a way of intruding and teaching hard lessons. The tension between those two beliefs would create his immortal book.”

Alas, it didn’t. After “La Côte Basque, 1965” appeared, Capote was banished from café society. C.Z. Guest was the only one who stuck by him. His calls to the others were not returned. “Answered Prayers” was never completed; a partial version was published posthumously.

Capote hadn’t understood his position. He was an interloper, welcomed by society only so long as he obeyed its rules. Mr. Leamer has delivered a fast-paced, sensitive tale of the swans, their tumultuous lives and their dismay at Capote’s treachery.

Ms. Hodgson is the author of “It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time: My Adventures in Life and Food.”

There is little doubt that his childhood friend Harper Lee helped him navigate the straight society of 1950's Kansas in order for him to write In Cold Blood. I guess many women percieved him to be harmless and at times "a little bitch."

The Book is

Capote’s Women : A True Story of Love and Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era

By Laurence Leamer