‘Boomers’ Review: Eminent Aquarians

By: By Barton Swaim

It is the commonest pattern in politics and society: Peace and prosperity, though good in themselves and furthering of human flourishing, eventually give place to arrogance, decadence and nihilism. “Beware,” God says to the children of Israel in the book of Deuteronomy, “that thou forget not the Lord thy God . . . Lest when thou hast eaten and art full, and hast built goodly houses, and dwelt therein; And when thy herds and thy flocks multiply, and thy silver and thy gold is multiplied, and all that thou hast is multiplied; then thine heart be lifted up, and thou forget the Lord thy God, which brought thee forth out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage.”

That, in a broad and secular sense, is the story of the baby boom generation. Americans born in the 20 years or so after the end of World War II were given quite a country. The destruction of Europe and Japan assured exceptional economic growth, social cohesion had been growing for decades, patriotism pervaded mass culture, and flush economies allowed white Americans to turn their attentions to the injustice of segregation. Yet by the end of the 20th century—the height of the boomers’ influence—the parties were at each other’s throat, popular culture had coarsened beyond recognition, racial tensions seemed to have worsened, and anti-Americanism had become the orthodox stance of the country’s educated elite.

It’s not fair to blame a generation for its own failures. The boomers worked with the material they were given, and part of what they were given was a lifeless religious establishmentarianism and an unthinking faith in the power of government. They rightly reacted against the first and embraced the second, but the point is: The baby boom generation didn’t invent themselves and can’t be blamed exclusively for their idiocies.

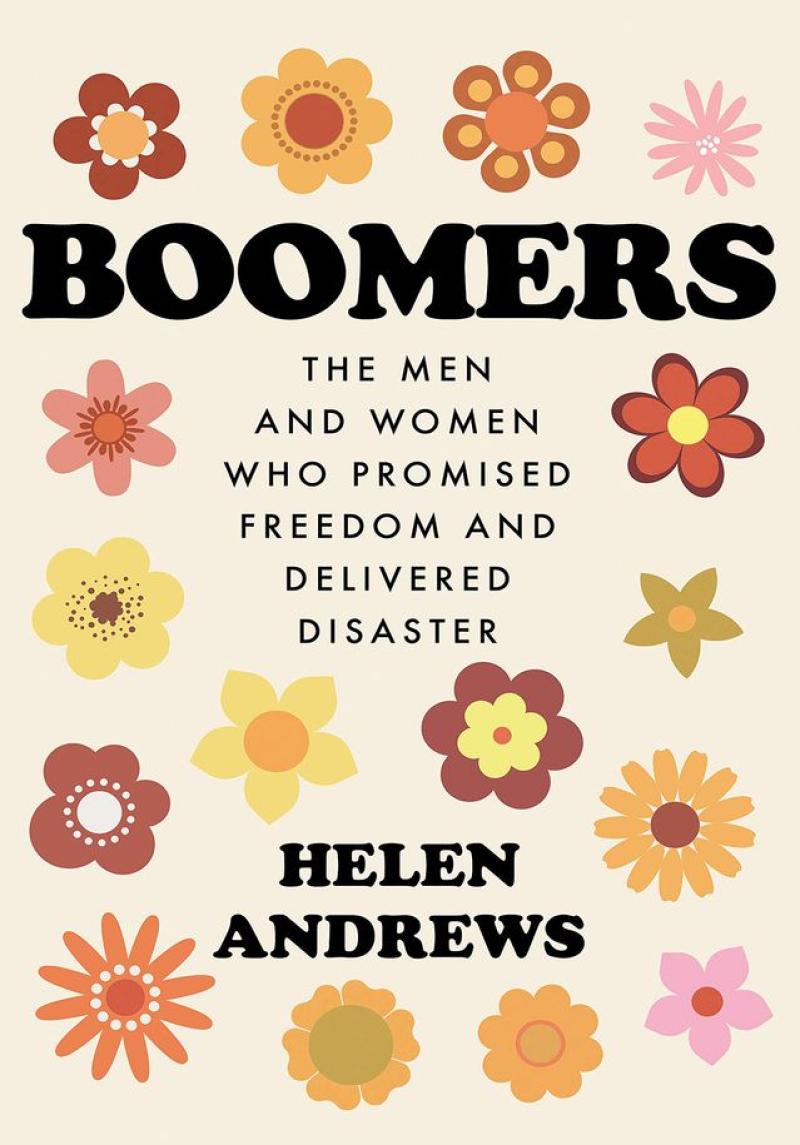

Still, it is a useful exercise to consider the attitudes and presuppositions that impelled members of a generational cohort to act as they did. That is more or less what Helen Andrews does in “Boomers: The Men and Women Who Promised Freedom and Delivered Disaster.” Ms. Andrews, an editor at the American Conservative magazine, is a gifted essayist with a delightful penchant for subversive and tersely worded insights. She has modeled her book on “Eminent Victorians,” Lytton Strachey’s series of mostly disparaging portraits of 19th-century luminaries. “Boomers” appraises six notables: Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, TV and film producer Aaron Sorkin, economist Jeffrey Sachs, feminist academic theorist Camille Paglia, racial rabble-rouser Al Sharpton, and Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor.

The chapters in “Boomers” aren’t portraits in the way Strachey’s were. They are essays, and often they stray pretty far from the subject. “The theme that connects all these seeming digressions,” Ms. Andrews writes, “is . . . the essence of boomerness, which sometimes manifests itself as hypocrisy and other times just as irony: they tried to liberate us, and instead of freedom they left behind chaos.” I’m not convinced that this theme, if that’s what it is, sufficiently connects all the discursive wanderings in these essays; you sometimes get the sense that Ms. Andrews wants to bring up a few points of irritation before she takes leave of the subject. But I don’t complain—she’s worth following. In a paragraph about the inflated importance of college degrees, she writes, apropos of not all that much: “In the first hundred days of his presidency Barack Obama proposed spending $12 billion on community colleges, which, if it had passed Congress, would only have resulted in more states deciding that firemen and state troopers must learn how to put their footnotes in MLA format before we give them permission to save our lives.”

Four of these essays hit their targets, two do not.

Jeffrey Sachs, the Harvard-trained economist who purports to tell developing nations how to develop, was an inspired choice. There is something fundamentally bogus about the whole enterprise of international economic development, and everybody knows it, not least the small-time autocrats and their hangers-on who profit from its largesse. Ms. Andrews is merciless. On the revelation that Mr. Sachs had delivered an impassioned speech about capitalism and greed to an Occupy Wall Street crowd: “Object to his endorsement of Occupy Wall Street if you must, but don’t call it hypocrisy. Occupy was exactly the sort of rebel movement that the United States would pour money into if this were a foreign country.”

Ms. Andrews’s scorching of Camille Paglia is similarly entertaining. Ms. Paglia, whose famous book “Sexual Personae” (1990) valorized pornography and sexual aggression in Western art, deserves some credit for spurning the dictates of political correctness. But she is, as Ms. Andrews rightly contends, a perfect symbol of the boomers’ project of counting their vices as virtues and expressing mild regret when the world follows their example. “While Paglia was busy descanting on the erotic qualities of the Pietà, men under forty were developing erectile dysfunction at unprecedented rates from watching too much Pornhub.”

Al Sharpton, for Ms. Andrews, epitomizes the boomers’ idealization of transformational, as distinct from transactional, justice: The former attempts to coerce society and threatens to destroy those parts of it that will not comply; the latter is content to negotiate small changes over time. Ms. Andrews’s chapter on Sonia Sotomayor portrays the associate justice as basically a bully—interrupting even fellow justices during oral arguments, using emotional blackmail in her opinions—and includes some wonderful asides about the notoriously dim midcentury chief justice, Earl Warren (“In a way, being dumb was Warren’s superpower. He was able to demolish long-standing precedents by pretending not to understand the reasoning behind them”).

These four essays exhibit the worst predilections of boomerness, but I couldn’t make out the point of her chapters on Steve Jobs and Aaron Sorkin. I am no fan of either—I look forward to the smartphone’s demise, and I find Mr. Sorkin’s hit TV series “The West Wing” risible. Ms. Andrews scores some nice lines against both men. But I did not discern a clear line of argument in these two essays.

Say what you will about Jobs, he spent his life creating and marketing things people found useful and worth paying for. Mr. Sorkin, too, whatever Ms. Andrews or I might say about his artistic productions, is wealthy because he has created things people enjoy.

All of which leads me to wonder if the essence of boomerness, the trait that disintegrated an earlier accord in American society, is a tendency to equate personal self-advancement with the creation of value. “Lest when thou hast eaten and art full . . . then thine heart be lifted up.”

—Mr. Swaim is an editorial page writer for the Journal.

Something tells me that Helen Andrews hits the target like one of Sherwood Forest's best archers. She was the managing editor of the Washington Examiner magazine and a 2017–18 Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

This is a story of a huge generation spoiled by those who survived the Great Depression and World War II.

Helen Andrews

The Book is:

BOOMERS

By Helen Andrews

Sentinel, 256 pages

Yeah, the counter culture didn't turn out as expected. But compartmentalizing the Boomers into post-World War II affluence ignores the times and is a disservice to the Boomer generation.

In the twenty years following World War II, kids had to become accustomed to living in the now. The Greatest Generation gave the Boomers a legacy of the BOMB. Everything could be wiped away in 30 mins. And the Korean War and Vietnam was not assuring. The Boomers never had control over anything. Barack Obama has been the only real Boomer President the country has elected.

Yes, it's fair to say the Boomer generation was self-centered and selfish. But the Boomer generation wasn't spoiled. The Boomer generations was raised in fear. You only live once and you must live in the now because tomorrow it could all be gone.

Did you ever fear "the bomb" growing up?

I never did. I always knew we had nuclear superiority......until now, that is.