'The Man From the Future' Review: The Genius of John von Neumann

By: Stephen Budiansky (WSJ)

Indiscriminately applied these days to everything from Elon Musk to tips for cooking chicken in your dishwasher, the word "genius" has arguably lost whatever meaning it might have had. But if anyone ever merited the label, it was surely the Hungarian-born mathematician John von Neumann. His unworldly insights into everything his wide-ranging intellect touched led colleagues to joke that he must be a superintelligent visitor from another planet, who had adopted the cover story of being Hungarian to explain away his heavily accented English.

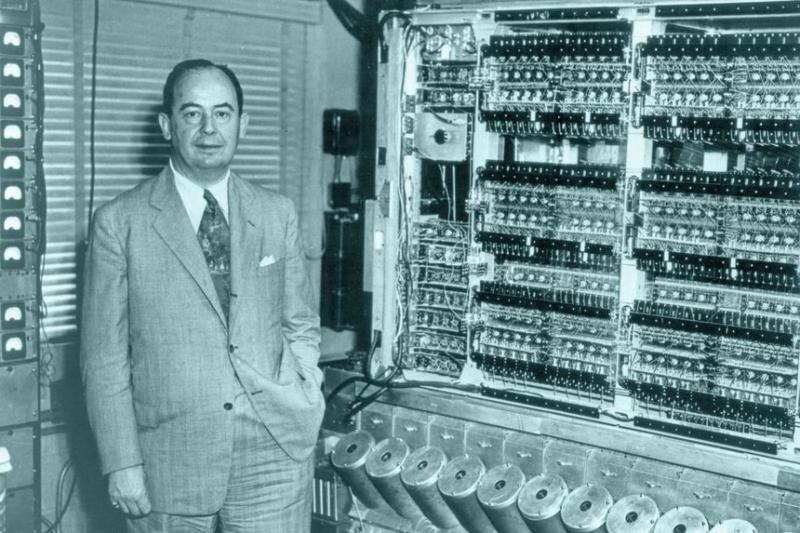

During his 53 years on Planet Earth—he died of metastatic prostate cancer in 1957—von Neumann, beginning at age 19, pioneered new areas of pure mathematics that today bear his name; revolutionized the foundations of quantum mechanics in the 1920s (among other things by demonstrating the deep mathematical equivalence of Heisenberg's matrix mechanics and Schrodinger's wave mechanics that had mystified everyone else); solved the crucial problem of employing high explosives to precisely and symmetrically compress a sphere of plutonium in the first atomic bomb; co-authored the bestselling book that launched the field of game theory; developed key concepts of nuclear deterrence and (before the first stored-program digital computer even existed) conceived the fundamental architecture used in every computer since.

“The Man From the Future” is an apt title for Ananyo Bhattacharya’s brisk exploration of the products of this astonishingly fruitful mind, and where his glittering array of contributions to such diverse fields have taken us since. “Look around you,” Mr. Bhattacharya writes with only slight hyperbole, “and you will see Johnny’s fingerprints everywhere.”

Mr. Bhattacharya, a physicist who previously worked as a science correspondent for the Economist and a staff editor at Nature, is a first-rate guide to the dauntingly complex nuts and bolts of these abstruse subjects. Although I am skeptical that any attempts at popular explanations of quantum mechanics can succeed, the author’s crystal-clear prose and his keen ability to relate the essence of mathematical and physical problems in understandable terms work just about everywhere else, making for a tour de force of enjoyable science writing. His elucidation of Kurt Gödel’s famous incompleteness theorem, which demonstrated that no axiomatization of a mathematical system which includes arithmetic can be both consistent (free of contradictions) and complete (every true statement can be proved) is the best I have ever seen, sacrificing none of the subtlety of the original argument while making Gödel’s ideas, and von Neumann’s related mathematical contributions, luminously clear.

A pair of chapters on game theory, the mathematics that underpins cooperation and competition, deftly explains what it is all about, tracing the revolutionary impact that von Neumann’s innovation had on everything from economics and nuclear targeting to evolutionary biology and bluffing strategies in poker, employing vivid examples ranging from Sherlock Holmes’s struggle with the evil Professor Moriarty to government auctions of the electromagnetic spectrum to illustrate the essential ideas.

As striking as von Neumann’s scientific intellect were his bon vivant’s zest for life and acute perception of human nature. These are not qualities typically associated with genius, much less with a child prodigy, which von Neumann undeniably was. As a boy he taught himself calculus; fluently mastered English, French, Latin, and classical Greek; and memorized entire stretches of a 40-plus-volume history of the world, which he was able to recite verbatim decades later.

Many prodigies go off the rails, but von Neumann did not. He loved company, excelled at both making money and spending it—on tailored clothes, Cadillac convertibles, first-class travel—and was famous for the endless flow of powerful martinis at unbuttoned cocktail parties at his luxurious home in otherwise stuffy Princeton. He was a master of smoothing over professional or political frictions among colleagues with a well-timed diversion into Byzantine history or, more often, a dirty joke or limerick, of which he maintained an endless store alongside the mathematical visions that filled his mind.

He also had a deep grasp of political realities exceptional for a scientist, or for that matter anyone. Mr. Bhattacharya quotes a remarkable letter von Neumann wrote a Hungarian colleague in 1935 predicting that there would be a war in Europe within a decade, that America would come to Britain’s aid, and that the Jews would face a genocide like the Armenians suffered under the Ottomans.

Beyond a selection of anecdotes that will likely be familiar to anyone who has heard of von Neumann, however, “The Man From the Future” has remarkably little to say about the man behind the ideas that Mr. Bhattacharya so ably brings to life. Much less does the author try to connect the ideas to the man, or explain how one person could influence so many aspects of modern life. Largely absent, too, is an account or explanation of what has often struck me as one of von Neumann’s rarest and most admirable traits, the lengths he would go to help colleagues. Notably, he put to use his keen understanding of institutional dynamics and the levers of power to untangle bureaucratic obstacles and locate jobs for fellow scientists fleeing Nazi Germany.

Norman Macrae’s 1992 “John von Neumann: The Scientific Genius who Pioneered the Modern Computer, Game Theory, Nuclear Deterrence, and Much More” sensitively and astutely explored this biographical territory; Macrae put his finger on the essential aspect of von Neumann’s personality when he described him as “an exceptionally well-balanced man” who “much preferred to give advice to those who asked for it, not to quarrel with those who did not,” an equanimity and self-assurance that was the secret to his getting so much done.

Perhaps Mr. Bhattacharya felt there was little point in replowing this well-tilled ground. He relies entirely on secondary sources, not even consulting the von Neumann papers at the Library of Congress, which include letters and telegrams to his two wives, financial records, day-by-day calendars of his activities and meetings—a lode of insight into his personal and professional life that has yet to be fully mined. Nor, except for quoting from a few passages that have appeared in print, does he make use of the voluminous and richly revealing diaries of von Neumann’s collaborator in game theory (and close friend in Princeton) Oskar Morgenstern, which have become available since Macrae’s book was published.

This necessarily narrows Mr. Bhattacharya’s portrait of his subject; it also leads him into some inaccuracy and injustice to von Neumann and others. He repeatedly claims that von Neumann advocated a preemptive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union, but nothing in von Neumann’s actual writings, public or private, support this often-made assertion, which I believe is based on a fundamental misinterpretation of his views. He glibly describes Oskar Morgenstern as an “oddball” because in Princeton he would go horseback riding wearing a suit and tie (actually not that unusual at the time); but Morgenstern’s diaries and letters show him, like his much beloved colleague von Neumann, to be an exceptionally balanced man, full of life, friendships and interests.

In other words, the one thing “The Man From the Future” is not is a biography of John von Neumann. It is, however, a marvelously bracing biography of the ideas of John von Neumann, ideas that continue to grow and flourish with a life of their own.

—Mr. Budiansky is the author of “Journey to the Edge of Reason: The Life of Kurt Gödel.”