'True' Review: Brooklyn and Beyond

By: David M. Shribman (WSJ)

Travel back three-quarters of a century, cross a border, imagine a world of fedoras and streetcars. There are smoked-meat sandwiches on warm plates and shivering commuters on cold corners. It is Montreal in 1946. Mobsters rule the street, the Catholic Church rules the soul. The mayor, who had encouraged Quebeckers not to register for the World War II draft, has won back his office after being sent to an internment camp for sedition. French and English mingle in the patisseries; furriers and longshoremen mingle by the river.

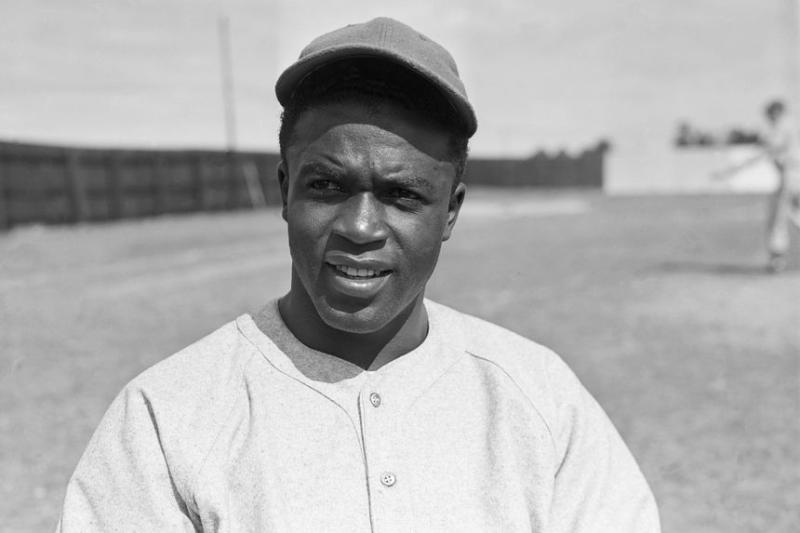

It was in postwar Montreal that the man who would break baseball's "colour barrier"—that is how the word was spelled in Montreal's morning Gazette and afternoon Star—began his star turn. Jackie and Rachel Robinson, known as the couple noir, lived on Avenue de Gaspe in the francophone neighborhood of Villeray. He took public transportation to the ballpark.

Montreal is at the center of one of the episodes that Kostya Kennedy presents in “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson,” a fresh and refreshing look at a twice-told (or more) tale. Certainly much of the Robinson story is familiar—the hotels (and ballparks) where he was locked out, the travails that he and Rachel experienced on the road, the taunts he heard on the field, along with the courage of Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers general manager who signed him, and of course the courage of Robinson himself. But it is Robinson’s time in Montreal that pulsates on the page.

“For the Robinsons, there was something sweet and welcome about Montreal,” Mr. Kennedy writes. “The city imparted a freshness and warmth despite the first seasonal chill—and it offered the promise of a respite.” Robinson was there to play on the Dodgers’ minor-league team, the Royals. He performed brilliantly during his season there, Mr. Kennedy tells us, showing outsize talent from the start. He hit .349, knocked in 66 runs and had 40 stolen bases—setting in motion the logic of his moving to the big leagues the next year. (My grandfather, who lived less than eight miles from Delorimier Stadium, was known to have skipped work to watch him play.)

Outside the park, Montreal offered a “respite” indeed. More concerned with how you prayed than how you looked, Montrealers treated Jackie and Rachel with characteristic Quebec nonchalance. Seen from the heights of Mont Royal, American race prejudice was a perverse peculiarity, one of many that prevailed down there, across the border.

The other seasons that Mr. Kennedy sketches have a resonance of their own: The summer of 1949—when Robinson was the first black player to start in an All-Star Game, standing along the

foul line between Ralph Kiner and Gil Hodges, then testifying on Capitol Hill about blacks’ democratic patriotism, offering an All-American counterpoint to the Soviet-admiring public advocacy of Paul Robeson. The autumn of 1956—when Robinson batted cleanup in the World Series at age 37, “his raw speed clipped but his instincts hardly dulled,” as Mr. Kennedy puts it. In that year he also succeeded W.E.B. Du Bois and Thurgood Marshall as a winner of the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal for his “civic consciousness”; and he played his final inning in a game he had changed forever. The summer and autumn of 1972—when the Dodgers retired his uniform number (42) and when the pallbearers at his funeral were a Dream Team of mourners, including Bill Russell, Don Newcombe and Pee Wee Reese.

As illuminating as these seasonal portraits are, what emerges from “True” above all is that Robinson was baseball’s man for all seasons, a mixture of great conscience, great grace and, not least, astonishing physical skill. (The book’s title alludes to an epigraph saying that, whatever the circumstances, Robinson “remained true”—to his convictions, among much else.) Robinson had a batter’s box stance that made him look, in Mr. Kennedy’s characterization, like “a sculpted pillar.” As a former UCLA stand-out on the gridiron, he possessed “a football player’s cruel, purposeful body draped now in the thick, loose-fitting flannel of his Dodger grays.”

At the plate, on the field, on the basepaths, Robinson was elegance personified. “He brought to the National League a dazzle and pluck,” Mr. Kennedy writes. His intelligence allowed him to “make up ground on players who had far more in-game experience.” On the Dodgers, only Robinson and Pee Wee Reese were allowed to decide on their own whether to steal a base. In the 1955 World Series, Robinson audaciously stole home even though the tying run was at the plate with two men out and with Brooklyn down by two runs.

Mr. Kennedy, the author of earlier books about Joe DiMaggio and Pete Rose, notes that Robinson was almost immediately drafted into political and social debate, presented as a symbol of the “nation’s better instincts as well as a reminder of its harshest sin.” But the “proscenium arch” of the ballpark was always the focus of his attention, “every diamond a stage.” Though the stadiums were often segregated, he captivated the whole crowd. Though blacks and whites returned home to different lives and different neighborhoods, “they had all seen Jackie Robinson play for the Dodgers, that much was true.”

Mr. Kennedy’s chronicle is less a biography of a man than a story of a distant time. On a July afternoon at the park, “there was not much more in the world that one could want than a Creamsicle or a Dixie Cup.” Yet Robinson was refused a taxi ride the year he was chosen MVP (1949). Along the way, “True” pays homage to a beautiful game that now—between truculent owners and players, a series of strikes, a surfeit of strikeouts, and an obsession with home runs—seems on the verge of ruin. Where have you gone, Jackie Robinson?

Mr. Shribman, a former Journal political writer, teaches in the Max Bell School of Social Policy at Montreal’s McGill University.

This is an American story that we never get tired of.

The Book is:

True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson