'Worse Than Nothing' Review: What Originalism Is and Isn't

By: Adam J. White (WSJ)

America's most solemn civic ceremony, the presidential inauguration, centers around the oath of office. The president swears to "preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States." But when the Constitution's meaning is the subject of heated disputes, what exactly is the president committing himself to?

The same question might occur to newly enlisted soldiers, when they swear their oath to "support and defend the Constitution" against "all enemies, foreign and domestic." Or to newly naturalized citizens, who do the same. Many of the Constitution's provisions are plain and precise, but others are "majestic generalities," as Justice Robert Jackson put it eight decades ago; they need to be interpreted by elected leaders, by civil servants and by citizens.

And by the Supreme Court, of course, which tends to be the final arbiter of it all. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes put the point bluntly a few years before his first appointment to the Court: “We are under a Constitution,” he said in 1907, “but the Constitution is what the judges say it is.” It’s not exactly true, but it’s true enough; look no further than our annual obsession with justices’ year-end blockbuster decisions. So on Inauguration Day, is the president pledging himself to preserve, protect and defend the musings of nine black-robed, life-tenured lawyers?

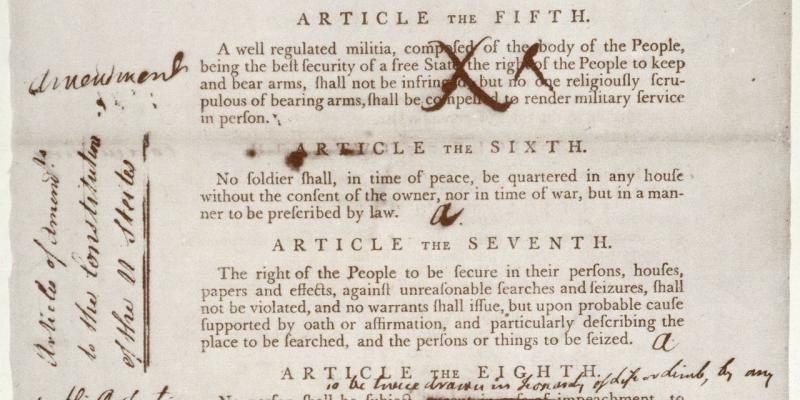

Forty years ago, conservative lawyers began to offer an alternative. They urged the Supreme Court to read the Constitution in accordance with the Founding Fathers’ original intent. “Originalism,” as it came to be known, emerged in the wake of decisions like Roe v. Wade , but also in the echoes of the nation’s bicentennial celebration, when Americans rediscovered their interest in—and affection for—the men who declared the states’ independence and who framed the nation’s republican Constitution.

The conservative legal movement began with law professors such as Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia, and a generation of law students who would found the Federalist Society and energize the Reagan Justice Department. Then came a wave of federal judges, including Bork and Scalia themselves, who applied constitutional originalism in actual cases. Their ideas gained weight in the courts of law and, crucially, in the court of public opinion.

Early on, originalists reframed their general notions of the Founders’ original “intent” into somewhat more objective considerations of the Constitution’s original public “meaning”—that is, of what a constitutional provision’s particular words meant to the public at the time of their ratification. Law professors published countless books and law-review articles analyzing the Constitution’s words, providing intellectual building blocks for Supreme Court lawyers’ briefs and justices’ opinions. In the Court, oral arguments re-centered around close analyses of the original meaning of statutory and constitutional texts, an approach known as “textualism.”

The first originalists and textualists were confident dissenters, in both academia and the judiciary. But after decades of research and argument, they now find themselves in the majority at the Supreme Court, even overturning Roe v. Wade itself.

Perhaps the best sign of the originalists’ success is the fact that so many progressive legal scholars and litigators now attempt to frame their own arguments in originalist (or at least “originalish”) terms, such as Yale law professor Jack Balkin’s Living Originalism. In 2015, one of President Obama’s own appointees to the Court, Justice Elena Kagan, told a Harvard Law School audience that “we’re all textualists now, in a way that just was not remotely true when Justice Scalia join[ed] the bench.”

But this summer Justice Kagan revisited her widely quoted quip. In West Virginia v. EPA , the Court ruled that climate regulators had exceeded the limits of the Clean Air Act, and she dissented from the majority’s reading of the law. “It seems I was wrong,” she wrote. “The current court is textualist only when being so suits it.”

Days later, at a judicial conference in Montana, she told the audience that inconsistency would undermine originalist judges’ credibility: “You have to apply methods that in fact discipline and constrain you, and you have to apply those methods consistently over cases, whether you like the outcomes they produce or whether you don’t like the outcomes they produce.” She was challenging originalists to be the best version of themselves.

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the Berkeley Law School, goes further. In “Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism,” he argues that constitutional originalism could never credibly constrain judicial discretion. “Originalism is not an interpretive theory at all,” he writes. “It is just the rhetoric that conservative justices use to make it seem that they are not imposing their own values, when they are doing exactly that.” His goal, then, is to “expose” originalism as not just a “fallacy” but a “dangerous” one.

Mr. Chemerinsky has long been one of the most pointed critics of originalism—and of originalist justices. When Chief Justice Roberts told his Senate confirmation hearing that judges should strive to be umpires who merely apply the rules instead of making them up, Mr. Chemerinsky blasted him in a law-review article: “Why did Chief Justice Roberts, who obviously knows better, use such a disingenuous analogy?”

His book continues in the same spirit. Originalism, he contends, suffers from five basic problems: It looks for fixed meaning in constitutional provisions that have none; it was not what the founders themselves intended; it produces abhorrent results; it cannot keep pace with the changes of modern life and governance; and originalism’s own practitioners abandon it when it produces results they don’t like.

Some of these criticisms contain a grain of truth. Take Mr. Chemerinsky’s contention that “the Framers likely did not want their views to control constitutional interpretation.” They surely understood that the Constitution, like all written laws, would be the subject of debate. James Madison, for example, warned in Federalist 37 that “all new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill,” contain obscurities and equivocations that need to be “liquidated and ascertained” through their application. And Madison, late in life, told a correspondent that the Framers’ own private debates at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia “can have no authoritative character.”

But when Mr. Chemerinsky quotes that warning, he neglects Madison’s punchline, from the very same 1821 letter: “the legitimate meaning of the Instrument must be derived from the text itself,” as informed by “the sense attached to it by the people in their respective State Conventions.” One can scarcely imagine a starker endorsement of at least some version of originalism and textualism.

Elsewhere, Mr. Chemerinsky’s brief against originalism suffers from blunt mischaracterizations of the cases and justices he criticizes. In his discussion of the challenges of modernity, for example, he notes the difficulty of applying the Fourth Amendment’s protection against “unreasonable searches and seizures” in an era of ubiquitous high-tech surveillance. It’s true, as he says, that the Fourth Amendment is among the Constitution’s most ambiguous provisions; its meaning isn’t clarified by asking what, say, Madison would think of modern police-surveillance technology. But Mr. Chemerinsky is completely wrong when he writes that “the originalist Justices—Scalia, Thomas and Gorsuch—have . . . adhered to the view that the Fourth Amendment applies only when there is a physical trespass.”

Mr. Chemerinsky’s criticism of the newest originalist justice, Amy Coney Barrett, is possibly the most misguided. He asserts that she has “told us that precedent and stare decisis should not matter in constitutional law.” That is astonishing, to say the least, given that Justice Barrett dedicated much of her academic career to studying the role of precedent in constitutional law. Those writings are nuanced, careful and much more even-handed than Mr. Chemerinsky suggests. In 2013 she lauded “constitutional stare decisis” as a useful tool for moderating disagreement among justices, enabling “a reasoned conversation over time between justices—and others—who subscribe to competing methodologies of constitutional interpretation.” In 2017 she wrote an entire article on productive relationships between originalism and stare decisis. With the title “Originalism and Stare Decisis,” it is hard to miss.

Mr. Chemerinsky’s fundamental criticism of originalism is that it’s unworkable. When vague constitutional provisions are susceptible to more than one possible interpretation, and historical evidence can point in different directions, originalism, he reasons, can’t “be applied to determinate results that are not the product of the ideology of the justices.” It is, he concludes, an “impossible” task.

Portrait of Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia (1936-2016). PHOTO: BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

As it happens, Justice Scalia himself recognized the practical challenge of originalism. “Its greatest defect, in my view, is the difficulty of applying it correctly,” he warned in a seminal 1989 essay. “Properly done, the task requires the consideration of an enormous mass of material” and an immersion in “the political and intellectual atmosphere of the time.”

For Scalia, however, this challenge paled in comparison to the problem faced by non-originalism: the lack of standards that can meaningfully constrain a judge’s own discretion. Scalia gave his essay a telling title: “Originalism: The Lesser Evil.” Mr. Chemerinsky’s brief against originalism, by contrast, makes no serious effort to weigh the alternative. He briefly discusses some things a justice might consider in deciding constitutional cases: historical practice, tradition (though never to “limit the meaning of the Constitution”), judicial precedent and foreign practices. These are laudable and useful—at least the first three—but he never attempts to explain how these would actually constrain judges in their interpretation of the Constitution.

In that respect, his book’s title is unintentionally revealing. For a constraint on judges, his alternative to originalism is, effectively, “nothing.”

Still, conservative judges and lawyers should not shrug off the criticism at the heart of this book. Mr. Chemerinsky argues that originalism does not actually constrain judges, either. With so much historical material available, “it is easy for originalists, or anyone, to pick and choose the sources that support the conclusion they want, and then declare that that is a constitutional provision’s original meaning.”

It calls to mind another line from Scalia, in another 1989 essay about the Court’s work. “As one cynic has said, with five votes anything is possible.” (The unnamed cynic was his liberal colleague, Justice William Brennan.) Originalism’s merits as a judicial methodology ultimately depend on judges’ willingness to recognize and heed their own limits: the limits of knowing the original meaning of some legal provisions, and, in cases in which the original meaning is reasonably in doubt, the limits of imposing an originalist interpretation to negate the laws of Congress or state legislatures.

In Federalist 78’s famous defense of the Supreme Court, Alexander Hamilton warned that judges would need to give a benefit of the doubt to the legislatures—it was, after all, a republican government. And judges would need to be “bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them.”

What truly “binds down” a judge, then, is the judge’s own self-restraint—his obedience to the oath that he, too, swore to the Constitution. Judicial power tempted generations of liberal judges to overstep the Supreme Court’s constitutional bounds. Conservatives will now be tested in the same way. Will they prove Hamilton and Madison right, or Erwin Chemerinsky?

Mr. White is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and co-director of George Mason University’s Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State.

I thought I owed our readers a fair review of the book we heard about here recently.

The book is:

Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism

By Erwin Chemerinsky

Yale University Press

264 pages

It doesnt really matter what rationale lawyers or judges use for defending , or attacking originalism, the obvious truth is that its claim to be the best and only way to interpret the constitution is totally subject to dispute and disagreement that cannot be just dismissed. In other words conservatives love it and the rest of us dont. .

There is no other way without violating the separation of powers.

The people alive in 1790 were inherently conservative when compared to many people living in 2022. That is just a fact . Many of the social trends and arrangements we take for granted today were not part of 1790. Women's rights and minorities rights are two most glaring examples. If we decide that originalism is the ONLY way to interpret the constitution we are saying that only conservative views can prevail in the courts. That view might prevail in a short run but there is no way it prevails in a long run.

LMAO! They were clearly different, but I wouldn't call them "Conservative."

That is just a fact . Many of the social trends and arrangements we take for granted today were not part of 1790.

That's true, John.

Women's rights and minorities rights are two most glaring examples.

Both were granted legally via legislation under the Constitution.

If we decide that originalism is the ONLY way to interpret the constitution we are saying that only conservative views can prevail in the courts.

No, John. There are things that are very ambiguous in the Constitution. That is what Congress is for! What is clearly written in the Constitution must be upheld by the Court until/unless the Congress amends it. It is actually a great system.

Very little is "clearly written" in the constitution, as Chemerinsky and many others have pointed out.

To take a line from Mr White: "Many of the Constitution's provisions are plain and precise."

Let's take the 2nd Amendment. It's very clear. It is also clear that it was written by our founders who feared Kings and dictators. They wanted the people to be able to keep and bear arms. Now if you think the 2nd Amendment is antiquated, then I agree. That means the Congress must follow the procedures listed under the Constitution to change it.

Do you think the founders intended regular citizens to have guns that can fire 100 rounds per minute? I dont.

They had no concept of such weapons.

To put it in the words of Marcus Aurelius, they had no idea of what Rome was to become.

Nonetheless, the Court must do it's duty and defend the 2nd Amendment. The Congress must amend the Amendment. I agree with Hamilton: "judges would need to be “bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them.”

It is up to an elected Congress to change what we both agree should be changed.

Sorry the second amendment isnt that clear. Anton Scalia, who wrote the Heller decision, said later that the second amendment rights were subject to reasonable restrictions. I think banning high speed weapons for everyday use is very reasonable.

Which doesn't mean the Amendment isn't clear. It means that types of weapons are not specifically mentioned and thus restrictions are possible.

Given the only weapon remotely capable at the time was the original Gatling Gun. I don't recall any kind of ban on that. But that's then. With that, firearms with that capability are banned from the general public from possessing. Although there are special permits available.

Now, if a change is needed to the amendment or the constitution, then there is a process for that. Remember that this process is not designed to be easy but must be followed.

What legal weapon has that as a sustained rate of fire?

Please define high speed weapons.

More in line with the time frame would be the older puckle gun . breach loading rifles were also at the time of the adoption a thing they knew about . The british used them with one regiment , they were delicate and expensive though .

What's better? There's a lot of talk about all the faults of originalism and rarely an offered alternative.

So rather than giving the words at issue their meaning, what's a better method of interpreting laws? What's the perfect method of interpretation that is always correct and never subject to disagreement?

There is probably nothing that wont be subject to disagreement. I think there is a fatal flaw to originalism , but one that is not really based on law, just overwhelming common sense.

It isnt possible for people in 2022 to know what the Founders intended in ways that were unexpressed at the time. It is ALL interpretation.

The originalist says "we're going to interpret the constitution according to the original text". It just cannot be done. They have to do so from 230 years later, which inevitably makes it a current day interpretation.

The alternative is to trash the Constitution.

We won't allow it.

No kidding. Pointing out that a school of interpretation is, in fact, a method of interpretation is pretty obvious. Scalia literally wrote a book about it called "A Matter of Interpretation" That is literally what judges do.

The issue, which you avoid, is what interpretative theory is better than believing that words mean what they say and interpretating them accordingly?

The alternative that no one wants to mention is the 'ends justify the means' rationalization of the Constitution. If the desired end (or outcome) is popular (endorsed by a plurality of the electorate) then the Constitution must be interpreted to justify that desired end. That's a tenet of the constructivist argument that the Constitution is a 'living document'.

e alternative that no one wants to mention is the 'ends justify the means' rationalization of the Constitution

100%. They don't want judges, they want the Supreme Court to consist of legislators and polling analysts.

“That's a tenet of the constructivist argument that the Constitution is a 'living document'.”

But to say ‘the ends justify the means’ is applying a misnomer…we have the means at any point in time to amend the Constitution, the ends are always available for reconsideration, at least for now.

Then amend the Constitution. Don't try to replace amendments with judicial decisions.

Stop conservatives from saying a law cannot exist unless is is written in the original (which would make most laws in the country null and void).

A ploy to get rid of only laws they don't like by using the judicial system.

That's not how our government or Constitution works. We have tens of thousands of laws that aren't mentioned in the Constitution, and no one believes they need be.

Yet on some laws like abortion, why does that need to be? Why are people picking and choosing which laws fall under that definition.

et on some laws like abortion, why does that need to be? W

I don't understand your point. The Supreme Court said the Constitution is silent on abortion and states can pass or not pass whatever laws their citizens want, or don't want to. It's the exact opposite of claiming a law cannot exist unless its written in the Constitution.

Why does that have to be a state law and not a federal one. It was a federal law for half a century.

Abortion access was never due to a federal law. The Supreme Court just invalidated state laws that restricted it.

What? They set abortion limits.

There was no federal law. If you think there was, please post it.

So if it was not considered a law it was considered a right?

But that's not what happens. SCOTUS does not have the Constitutional authority to replace the legislative process or to amend the Constitution by judicial decision.

SCOTUS exceeded its Constitutional authority with the Roe v. Wade decision (which became a woman's right to choose). SCOTUS unilaterally established a right by ignoring Constitutional checks and balances and assuming a governing authority that the Constitution does provide.

Roe v. Wade broke the Constitution and, in reality, created a Constitutional crisis.

“…(which became a woman's right to choose). SCOTUS unilaterally established a right by ignoring Constitutional checks and balances and assuming a governing authority that the Constitution does provide.”

It is your contention the Constitution does not allow a woman autonomy over her own body? If so, and so be it if that be the case, do you allow the courts a remedy to right an obvious wrong?

Yeah, that's what the Court said. It created a right and then used it to strike down laws passed by legislatures.

It is my contention that legislatures write law; courts do not write law. It is my contention that rights are added to the Constitution by amending the Constitution and not by judges making decrees.

Democracy ain't as easy as obtaining political power. And the means to achieve a political end cannot be rationalized away. The Constitution delineates the means, so defending the Constitution is really about following the processes, procedures, and means set forward by the Constitution. There aren't any shortcuts that can be justified by rationalizing away the intent of shared governing authority spelled out in the Constitution.

Legislatures can establish a woman's freedom to choose by writing law. But the woman's freedom to choose cannot become a right without amending the Constitution.

I honestly don’t believe that a lot of judges are saying “I know that the Founders/Congress/Legislature meant to say X and wrote it down that way, but since circumstances/word usage has changed, I’m going to rule that the law says the exact opposite of what I know they meant. I really don’t think anyone is doing that. I think for the most part, judges respect the plain language of the law within the context of what they reasonably believe was intended.

People can believe a wild spectrum of things. Judges are no different Imo.

The Supreme Court has taken crystal clear statutory language outlawing racial discrimination in employment and ruled that the unambiguous language means the opposite of it what it says.

It happens.

In their opinion. That’s different than the situation I was describing. The fact is reasonable people disagree about what a thing means all the time. It’s doesn’t mean they’re deliberately ignoring what they think the law is.

It’s doesn’t mean they’re deliberately ignoring what they think the law is

There's no other way to explain claiming this language justifies racial discrimination.

There's no good faith argument to be made.

A lot of people say that whenever someone disagrees with them.

Then make one.

Explain how this sentence permits racial discrimination by an employer:

You want me to support an argument someone else made? Based on one sentence? That’s not rational.

You want me to support an argument someone else made?

since you claimed there's a good faith argument to be made, I want you to make it. Given your dismissive response, it should be easy.

It's a simple exercise in reading comprehension. Explain how the statutory language I quoted can be used by a Court to justify racial discrimination in employment. Or simply admit that the Court will in fact ignore unambiguous language to issue rulings that contradict the plain meaning of statutes.

I made no such claim. You produced your quote and you made the claim,

All I said was,

Which is true, in my opinion. I made no particular claims as to your specific quote. And I am not going to go to the trouble of analyzing a single statement from a much larger argument with no context just so you can get a thrill up your leg over an internet debate only you care about.

Is it simple? I very much doubt that. How many pages in total is the document you are quoting from? How many levels of litigation did it go through? How many briefs were filed and how long were they? How about amicus letters? How about oral arguments? There’s nothing “simple” about what you think you want.

lot of people say that whenever someone disagrees with them.

Then Explain how this sentence permits racial discrimination by an employer:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for any employer, labor organization, or joint labor-management committee controlling apprenticeship or other training or retraining, including on-the-job training programs to discriminate against any individual because of his race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in admission to, or employment in, any program established to provide apprenticeship or other training."

Everybody is an originalist/textualist at some point. But just because something is printed in black white, that doesn't make the law "clear." Cases go all the way to the SCOTUS just to settle the meaning of one word. As Bill Clinton well knew, it all depends on what the meaning of the word 'is' is.

One of the other problems with originalists/textualists is this tendency to say that this or that right or power isn't in the Constitution. They're right, of course, but even the most strident textualists have been willing to carve out exceptions. And too often, in my opinion, they forget that per the text of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments, not everything needs to be in the Constitution.

I believe that one of the obvious intentions of the Framers was that the Constitution be vague and open to interpretation. Its sheer brevity makes plain that they weren't trying to cover every eventuality. (The US Constitution is actually one of the shortest in the world.)

I totally agree. It was left to be updated with the times...within limits.

Originalism is a relatively new concept, supposedly somehow tied to the Federalist Papers, which I find amusing since the Federalist Papers were written anonymously by 3 different men, who also didn't agree with each other, to a NY paper, to get NY delegates of the Constitutionalist Convention to vote for the Constitution as it stood. They were never meant as a tenant for SCOTUS.

If the Constitution was not meant to be changed, it wouldn't have given us room for amendments.

Exactly. That's how it's changed. If it was meant to simply change at the whims of judges, there would be no need for an amendment process.

Correct. We change it with our elected officials passing an amendment, not by judges finding rights in the sky.