'Life of a Klansman' Review: A Hood in the Closet

By: W. Ralph Eubanks (WSJ)

If there is a lesson to be learned from the first 20 years of this century, it is that the force and impact of history are inescapable. In the spotlight cast by Black Lives Matter, Americans have witnessed how certain elements of our cultural memory cry out to be recognized and cannot continue to be ignored or disguised by mythology. Yet in spite of hard evidence, it is difficult for Americans to come to terms with the burdens and wrongs of the past. The demons lurking in family chronicles and stories—transgressions shrouded in silence, euphemism or willed amnesia—are often the most difficult to exorcise; they inevitably bring up questions of legacy and inheritance.

Edward Ball’s tangled family history has long preoccupied him as writer of narrative nonfiction. More than 20 years ago, Mr. Ball examined the lives of his South Carolina ancestors in his National Book Award-winning book “Slaves in the Family,” which focused on black and white Americans’ shared history of slavery. Digging into his family’s slaveholding past—between 1698 and 1865, close to 4,000 blacks were either purchased by the Balls or born on of their 20-odd plantations—was, the author wrote, “a bit like doing psychoanalysis on myself,” because it made him come face-to-face with how the ways of the plantation system may have shaped his own identity and the very path of his life.

In the opening pages of “Slaves,” Mr. Ball mentioned that “someday I may look into my Louisiana family” because, like his Carolina family, they too were slaveholders. That is exactly what he does in “Life of a Klansman,” though this time he digs deeper by examining how white supremacy is as much a part of his family history as the institution of slavery. The result is brave, revealing and intimate, an exploration of how one family’s morally complicated past echoes down to the present. This is a story for our cultural moment, as Americans begin to engage with and acknowledge the ways white supremacy endures in our society. Needless to say, this is not a sweet and tidy tale.

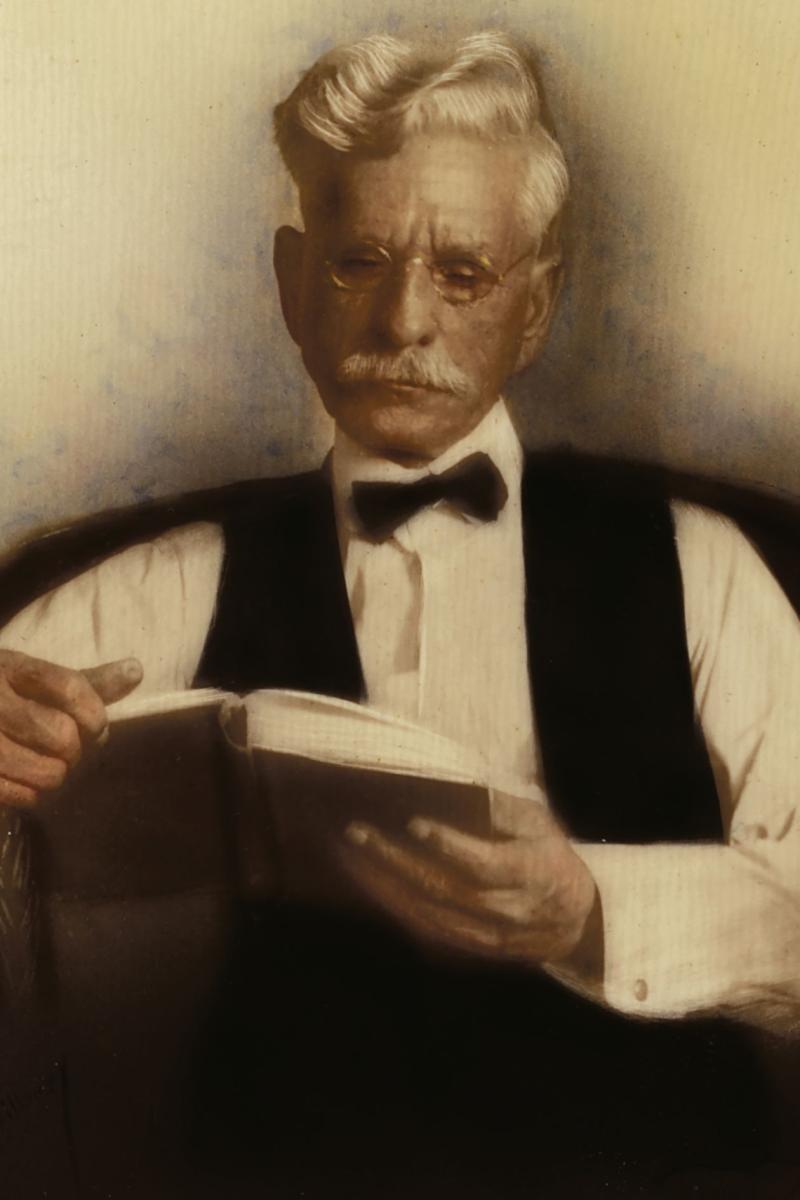

In “Life of a Klansman,” Mr. Ball reconstructs the life of his great-great-grandfather Polycarp Constant Lecorgne (1832-86), a white French Creole working-class carpenter who lived in New Orleans. Born to a mother from a plantation-owning family and a father who had deserted from the French navy, Lecorgne watched his parents’ fortune wax and wane on the back of the slave trade. Unlike the story of Mr. Ball’s South Carolina family, which was based on their extensive, well-kept records and ledgers, the story of the Lecorgnes was difficult for the author to piece together. Using public records, Mr. Ball traced the family’s many changes of residence as well as the black men and women they bought and sold. He tells how Constant Lecorgne moved down New Orleans’s social ladder—from the white moneyed class to the working class—and, in his late 20s, joined the Confederate Army when the Civil War erupted in 1861. Summarily kicked out for taking part in an alcohol-fueled riot, he later rejoined but found himself adrift after the war’s end.

In the early 1870s Lecorgne found a new purpose: He became part of New Orleans’s White League, a white-supremacist paramilitary outfit. The League was part of a network of organizations in Reconstruction-era Louisiana, including the Ku Klux Klan and the valiantly named Knights of the White Camellia, whose collective purpose was, in the words of the Knights’ founder, to protect the white race “from amalgamation and miscegenation and other degradations.” Chapters of the League emerged all across the Reconstruction-era South, with the avowed purpose of overthrowing Republican governments and restoring white supremacy. “The only difference between the White League and the Ku-klux was the League was not secret,” Mr. Ball writes. By night-riding and committing acts of terror against people of color, the League won back the rule of white people and helped end Reconstruction in Louisiana.

Although he was not a leader in the League, Lecorgne was a devoted foot soldier. Mr. Ball traces Lecorgne’s involvement with racial violence, beginning with anecdotes from family folklore and then moving into concrete court records that reveal how Lecorgne and some of his associates were indicted for treason against the U.S. government and for breaching the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. In the end, all charges were suspended and the violence against black residents of New Orleans continued. He tracks Lecorgne’s subsequent involvement in fighting for white supremacy by following clues in period newspapers and accounts left behind by the leaders who would have directed him. He finds strong circumstantial evidence linking his ancestor to continued uprisings against Reconstruction, including the climactic 1874 Battle of Canal Street, in which some 5,000 white supremacists confronted the Louisiana militia and the New Orleans police in an unsuccessful attempt to unseat the state’s Republican governor, William Pitt Kellogg.

While the life of Mr. Ball’s great-great-grandfather is the focus of “Life of a Klansman,” the culture and particulars of 19th-century New Orleans function as a kind of composite supporting character, illuminating local issues of racial caste and social hierarchy as well as larger regional trends. Mr. Ball artfully reanimates ideas that attempted to justify slavery and, later, black subjugation. “The names Samuel Morton and Josiah Nott,” he writes, were “murmured and admired in New Orleans.” Both of these influential figures—Morton a Philadelphia Quaker, Nott a Southern academic—were physicians who believed the races were created separately and endowed with unequal aptitudes from the start. Morton was a great influence on the Swiss-born biologist and polymath Louis Agassiz, a Harvard professor whose ideas took hold nationally. In 1863 Agassiz wrote that blacks were “incapable of living on a footing of social equality with the whites, in one and the same community, without becoming an element of social disorder.”

Mr. Ball also connects historical New Orleans with the present moment, as when he interviews the descendants of black and Creole families who were victimized by White League violence, showing how past trauma lives on in the stories of many of the city’s current residents. Instead of taking the testimony of these families and braiding it together with that of his own, Mr. Ball sets this section of the book apart. It’s a risky but effective narrative gambit, revealing that while Mr. Ball may share the history of the people he is interviewing, the impact of that shared history is both infinitely varied and painfully particular.

“I am trying to open a small window into U.S. history,” Mr. Ball writes toward the end of “Life of a Klansman.” “I am trying to bring whiteness up from its unconscious storage place into nascence, which is that feeling just short of consciousness.” “Life of a Klansman” does just that; it helps the reader to understand that uncomfortable historical legacies must be faced and confronted. Though Mr. Ball shies away from prescriptiveness, the tensions in the stories he tells make it clear that he wishes to throw off the “straitjacket of whiteness” that was tightly wrapped around his ancestors. His prose is almost never cloying or superficial; this is not a handwringing apology of the sort one sometimes reads in social-media confessionals. Mr. Ball is movingly philosophical about what responsibility his generation holds for the sins of its fathers. He veers away from sentimentality and bluntly admits that “we can never make out our personal links to the felonies of history.” But he also understands that the folkways and traditions of past generations weigh heavily upon the souls of the living. While he admits feeling guilt about his family’s history, he also recognizes that his “guilt is something like a stage of grief.”

In “Life of a Klansman” Edward Ball reveals how American culture has been built on generation after generation of unresolved grief connected with racial violence. Rather than seeking ways to harness the transformative power of confronting the history of racial oppression and white supremacy, Americans have chosen to ignore it or normalize it. That is what Mr. Ball’s family did for years by benignly referring to Polycarp Constant Lecorgne as “our Klansman” without acknowledging the gravity of his actions. Similarly, when the city of New Orleans placed the White League’s memorial to the Battle of Canal Street on public land, it also glossed over the past. After its installation in November 1891—during a time when Louisiana was busy disenfranchising African-American voters—an inscription was added to the base of the memorial: “The national election in November 1876 recognized white supremacy and gave us our state.”

In the spring of 2017, the city of New Orleans removed the monument to the White League. The base of the obelisk on Canal Street today stands empty, no longer an intimidating presence on the landscape. Now that other such statues are coming down and American society is beginning to reckon with its history of racial violence, Mr. Ball’s examination of the life of his family’s Klansman reminds us that there’s much more work to be done. “Racial identity, deeply embedded, cannot be removed and replaced, like computer memory,” he writes. “What is possible is to acquire some awareness of racial formations inside the self and to place that awareness with other sentience possessed by ‘knowing man.’ ” Bearing witness to the historical impact of white supremacy, as Mr. Ball does in this book, is a step toward achieving that awareness.

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Tags

Who is online

54 visitors

Definition of masochist

1 : a person who derives sexual gratification from being subjected to physical pain or humiliation : an individual given to masochism

I'm sure some of our friends here on NT would enjoy reading this one. Speaking for all those who have no connection to the long remembered institution of slavery, I say enjoy it in silence.