'Countdown 1945' Review: Checkmate in the Pacific

By: James D. Hornfischer (WSJ)

On the night of Aug. 9, 1945, with the Japanese war effort in full collapse, Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu, a member of Emperor Hirohito’s all-important Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, told his colleagues in the presence of the emperor: “We cannot promise victory, but we are not yet defeated. We are aware that the war situation is difficult, but with the determination of one hundred million people and with further preparations, it might be possible to find life in death.”

In “Countdown 1945: The Extraordinary Story of the Atomic Bomb and the 116 Days That Changed the World,” Chris Wallace, the anchor of Fox News Sunday, has made a taut nonfiction thriller out of the dramatic days between Harry S. Truman’s succession to the presidency, following Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945, and the dropping of the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki less than four months later. Structured as a series of datelined vignettes and fashioned as a countdown, the narrative lopes through its well-chosen selection of historical moments. This is a deeply absorbing reading experience about the fateful final months of a conflict that deserves to be known in detail to all Americans. It is what a popular history book should be: propulsively paced; well researched in primary sources; and written with sympathetic imagination, bringing people to life in their important moments. It will encourage and enrich many conversations on its subject.

Mr. Wallace and his collaborating writer, the journalist Mitch Weiss, give us a rich cast of characters, foremost President Truman, who was deeply shaken when he first learned of the existence of the atomic bomb shortly after Roosevelt’s death. “He was shocked,” the authors write, “that a project of this size and expense, with plants across the nation, had remained a secret.” The president was also concerned “with its short-term implications for international relations, especially with the Russians.” Coaxing Stalin to join the war effort against Japan was a top agenda item for Truman. But most of all, the president feared the “long-term consequences for the planet.” As Gen. Leslie Groves, the military commander of the Manhattan Project, wrote in his presidential briefing: “Atomic energy, if controlled by the major peace-loving nations, should ensure the peace of the world for decades to come. If misused it can lead our civilization to annihilation.”

As U.S. victories over Japan piled up, from the fall of Saipan in July 1944 to Okinawa in June 1945—Hirohito and his war council seemed impervious to the logic of defeat. In war, as they understood it, the victor does not determine when the war ends. Only a defeated power has the privilege of deciding when the fighting will stop. But Umezu and his fellow bitter-enders—Gen. Korechika Anami and Adm. Soemu Toyoda—held to a number of surrender demands that went well beyond the retention of Hirohito on the throne. They insisted upon no occupation of Japan by U.S. forces, and war-crimes tribunals and a disarmament process run by Japanese authorities alone.

It required two atomic-bomb attacks to shake the Japanese leadership from this self-destructive madness. Only after Nagasaki was struck by the second bomb on Aug. 9 did Hirohito finally speak his mind on the question of ending the war. Surrender without conditions, he told the war council, was “the only way to restore world peace and to relieve the nation from the terrible distress with which it is burdened.” Among these hard men, tears flowed.

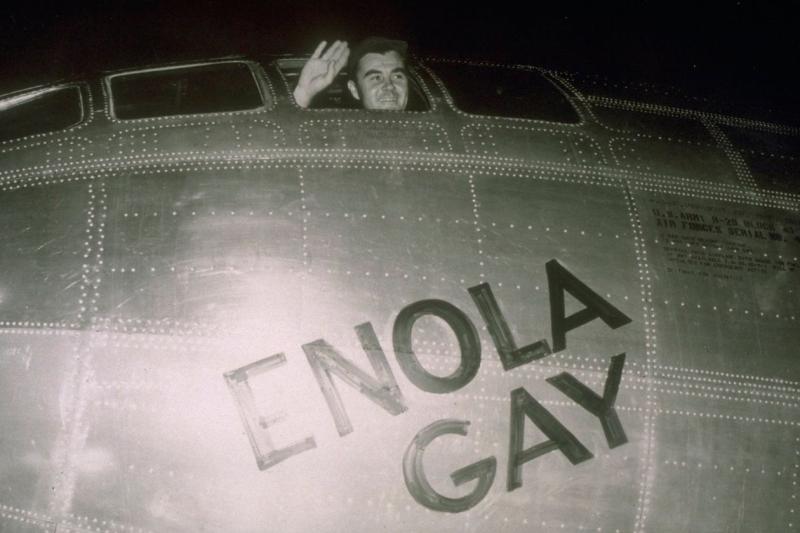

Messrs. Wallace and Weiss give us vivid and engaging portraits of Col. Paul Tibbets Jr., who 75 years ago today flew the B-29 bomber known as Enola Gay on its mission to Hiroshima; Tibbets’s air crew, notably his navigator, Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk, and his bombardier, Tom Ferebee; Robert Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists at Los Alamos; and a number of individuals whose lives would be irrevocably altered if an invasion of Japan went forward.

Truman’s Pacific commanders were marshalling three-quarters of a million troops for Operation Downfall, as the planned ground invasion of Japan was known. The president knew it was to these troops that he owed the greatest consideration. As many as a third of the invasion force would not survive or come back whole. “A quarter of a million of the flower of our young manhood were worth a couple of Japanese cities,” Truman would later say. The bomb was “the most terrible thing ever discovered,” the president wrote in his diary, “but it can be made the most useful.” The “chilling cost of failing to use it,” the authors write, outweighed the president’s desire to avoid it.

On the Pacific island of Tinian, near Guam, as Tibbets and his crew prepared to take flight on Aug. 6, the day began with a prayer. The Lutheran chaplain attached to Tibbets’s group intoned: “Almighty Father, Who wilt hear the prayer of them that love Thee, we pray Thee to be with those who brave the heights of Thy heaven and who carry the battle to our enemies.”

Those enemies, Truman finally judged, were “savages, ruthless, merciless, and fanatic.” Without the atomic bombs, the Pacific war almost certainly would not have ended in 1945. Truman’s fateful decision saved innumerable lives on all sides by compelling a war-mad Japanese leadership, at last, to reckon with reality.

Hirohito’s dramatic conference with his war council is unaccountably not part of the book’s sequence of dramatic vignettes. Nonetheless, for its vividly drawn coverage of the American side of these pivotal events, the book is deservedly the nonfiction blockbuster of the season.

Mr. Hornfischer is the author, most recently, of “The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944-1945.”