'Leave It as It Is' Review: 'Man Can Only Mar It'

By: Gerard Helferich (WSJ)

More than a century after his death, Theodore Roosevelt still inspires with his ferocious energy, consummate intelligence and manifold achievements. But perhaps most fascinating is his complex, even paradoxical, personality. A man with genuine empathy for the disadvantaged, he embraced the racial and cultural prejudices of his time; an avowed trustbuster, he accepted the patronage of banks and corporations; a steadfast conservationist, he slaughtered hundreds of wild animals. Today, when the legacies of many American heroes are being re-examined, what are we to make of Teddy Roosevelt?

The Grand Canyon from the South Rim in Arizona at dawn.

PHOTO: PATRICK GORSKI/NURPHOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES

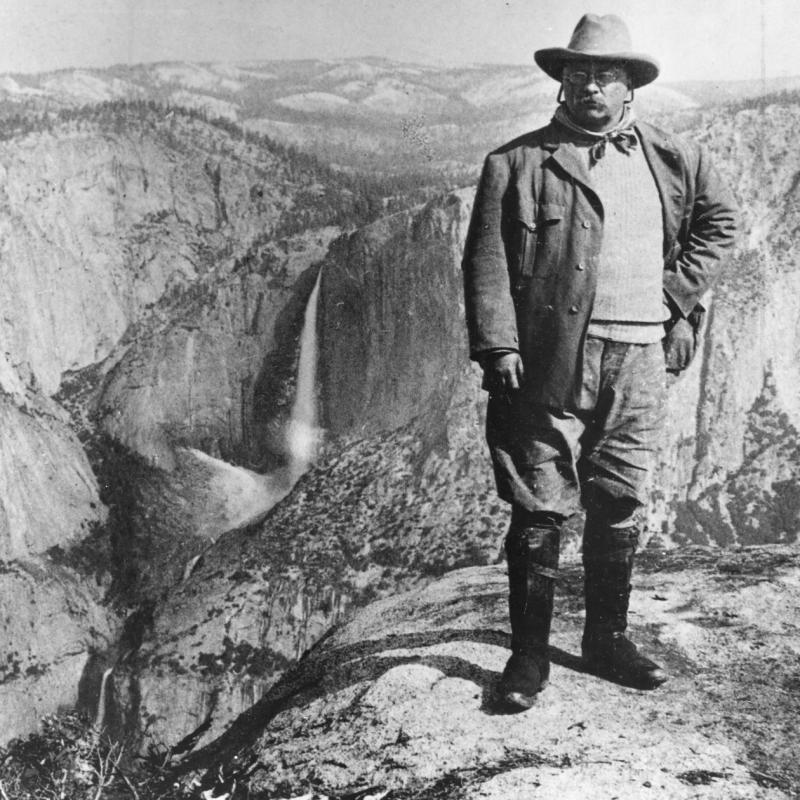

David Gessner considers Roosevelt's environmental record in his thoughtful "Leave It as It Is." The title comes from a speech that TR gave at the Grand Canyon in 1903, exhorting his fellow citizens: "Leave it as it is. You can not improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it."

The phrase was the watchword of Roosevelt's conservationist ethos. As president, he set aside 230 million federal acres for posterity, creating five national parks, 51 federal bird preserves, four national game preserves and 150 national forests. He also designated 18 national monuments, including the Grand Canyon, later named a national park. In establishing these monuments he invoked the Antiquities Act, which he had signed in 1906; it gave presidents the authority to protect federally owned "historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest." Taken as a whole, Roosevelt's record is unparalleled, and Mr. Gessner is right to call TR "our first and greatest environmental president."

In shielding federal land from unbridled development (as in many other matters), Roosevelt was often opposed by powerful commercial interests and a reluctant Congress. Today conserving wilderness areas is still unpopular among those who believe, as candidate Donald Trump declared in 2016: "We'll be fine with the environment. We can leave a little bit, but you can't destroy businesses." In 2017, to free up more public land for mining and oil and gas drilling, Mr. Trump drastically reduced the size of two scientifically and culturally important national monuments, Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, both located in Utah. (The former was designated a national monument in 2016, by President Obama; the later by President Clinton in 1996.) Removing nearly two million acres from protection, it was the greatest rollback of its kind in history.

The action inspired Mr. Gessner, a writing professor and environmental author, to make a cross-country drive to the threatened monuments, as well as to several sites that had inspired Theodore Roosevelt, including the Badlands of North Dakota, Muir Woods in California, and the Yellowstone, Yosemite and Grand Canyon national parks. En route, the author was hoping to reconnect with his hero and to find a relevance for TR in our own era. Not least, he was looking for reasons to hope.

The road trip forms the backbone of his book, but Mr. Gessner fleshes it out with succinct sections on Roosevelt’s life, especially the periods that helped to shape his environmentalism, such as his boyhood, when he became enamored with natural history, and his stint as a rancher in North Dakota. He especially delves into Roosevelt’s presidency, where TR’s environmental legacy includes, most tangibly, all those national parks, preserves, monuments and forests. But through his bully pulpit, his books, articles and speeches, Roosevelt also inspired his fellow Americans to care about the environment and to see it in a new way. “One of Theodore Roosevelt’s great legacies,” Mr. Gessner writes, “was giving us a story to tell ourselves about this country and its land.” TR believed, he adds, that the land “was part of us, and we were part of it. It defined us, and our love for it was one of the best things about us. These ideas may now sound like platitudes; to him they were felt truths.”

Yet on the environment, Roosevelt’s record is not pristine, especially as it concerns Native Americans. An ardent advocate of Manifest Destiny, he published a four-volume history, “The Winning of the West,” whose title aptly captures his point of view. He could never accept what happened to Native Americans as genocide, and when the presence of Native peoples stood in the way of perceived progress, including the creation of national parks and monuments, his solution was to remove them from the land and to urge assimilation into the dominant culture.

Mr. Gessner doesn’t excuse Roosevelt’s limitations and hypocrisies, but neither does he want them to cancel his signal achievements. “We are all hypocrites,” he writes, quoting his friend the environmental planner Dan Driscoll. “But we need more hypocrites who fight.” And there’s no question that Roosevelt was a fighter for what he believed in, including the natural world. Perhaps his greatest environmental contribution was to promote a wider vision, beyond the anthropocentrism that Mr. Gessner warns is destroying the planet. “For all his self-centeredness and egotism,” the author writes, “he seemed to understand this primary insight: that the world is more important than we are.”

As we face environmental dangers unimagined in Roosevelt’s day, Mr. Gessner asks what TR would do with our surviving wilderness. The impassioned response: Leave it as it is. Although protecting public lands, in itself, won’t reverse global warming, it could play a key role in counterbalancing carbon emissions and preserving imperiled species. And maybe he is naive, the author admits of himself, but he believes that “wild, beautiful land is the greatest thing about our country. It is the single best reason for hope. . . . A physical statement of our belief in the future.” Or as Theodore Roosevelt put it more than a century ago: “There is nothing more practical than the preservation of beauty.”

Mr. Helferich’s most recent book is “An Unlikely Trust: Theodore Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan, and the Improbable Partnership That Remade American Business.”

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

Article is LOCKED by author/seeder

"As we face environmental dangers unimagined in Roosevelt’s day, Mr. Gessner asks what TR would do with our surviving wilderness. The impassioned response: Leave it as it is. Although protecting public lands, in itself, won’t reverse global warming, it could play a key role in counterbalancing carbon emissions and preserving imperiled species. And maybe he is naive, the author admits of himself, but he believes that “wild, beautiful land is the greatest thing about our country."