'Levon' Review: The Beating Heart of the Band

By: David Kirby (WSJ)

It came from somewhere in the woods, rising like a mist off a clearing. Nobody knew what it was, just that it was different. It began with a child plucking a length of baling wire nailed to a porch rail. It began with a choir in a little clapboard church with a leaky roof, and it began with a handful of farmers and mechanics making music after hours with a washtub bass and a guitar and a seed box instead of a drum. It was homemade and handmade. The blues flowed into it, as did gospel and country. At some point somebody plugged it in, amped it up, and started selling it to a new breed of American—young people with their own cars and hairstyles and a desire for this music that was akin to a junkie's addiction, a lover's lust.

Rock 'n' roll has been made in high-tech studios ever since, but it started in and around towns that nobody knew the name of unless they lived there. Like Turkey Scratch, Ark., where Levon Helm moved as an infant and spent his earliest years. His father was a sharecropper, and Helm, born in 1940, went to work in the fields as a waterboy and then a regular farmhand. ("I was a pretty good tractor driver," he remembered, "but I just didn't have the heart for it.") The boy made it through high school—barely—and started his show-biz education almost accidentally.

In the 1940s and '50s, traveling shows would crisscross the country, setting up a tent or turning a truck bed into an improvised stage. Helm's favorite was F.S. Walcott's Rabbit's Foot Minstrels, which featured an emcee, blackface comedians and chorines doing "the hoochie-coochie" if you stayed for the late show. In high school he formed a band called the Jungle Bush Beaters, and soon came to the attention of a journeyman rocker named Ronnie Hawkins, front man of a band called the Hawks, who just happened to need a drummer. The Hawks would eventually become the band known as The Band, and Helm its most important member—although he wouldn't have said that about himself.

The death of John Prine earlier this year sparked a renewal of interest in Americana, a musical melange that not only borrows from artists as different as Howlin' Wolf and Hank Williams but harkens back to the old, weird America of Walt Whitman and Johnny Appleseed. Over time the fabric of Americana unraveled some—into the blues, country, rockabilly, rock 'n' roll—but the threads weave back together whenever a group of young musicians steps back a century or so and plays a music that may be hard to classify but sounds both hauntingly familiar and strangely new. The Band embodied every aspect of that music, and in "Levon Helm" Sandra B. Tooze (who has also written a book on Muddy Waters) brings a man and a musical era to life.

Ronnie Hawkins was not exactly a shrinking violet. He routinely did front flips off the stage; if there was a wall to the side, he'd run at it and do a back flip while still holding the mic. The venues the Hawks performed in weren't Carnegie Hall, either, and when 17-year-old Levon Helm joined, they played the kinds of places where, in Ronnie Hawkins's words, "You had to show a razor and puke twice before they'd let you in." They toured Arkansas and its environs unceasingly, sometimes making as little as $10 a night and, when they ran out of gas, resorting to what Mr. Hawkins called "the Arkansas credit card," a length of hose used to siphon fuel from a car in a roadhouse parking lot.

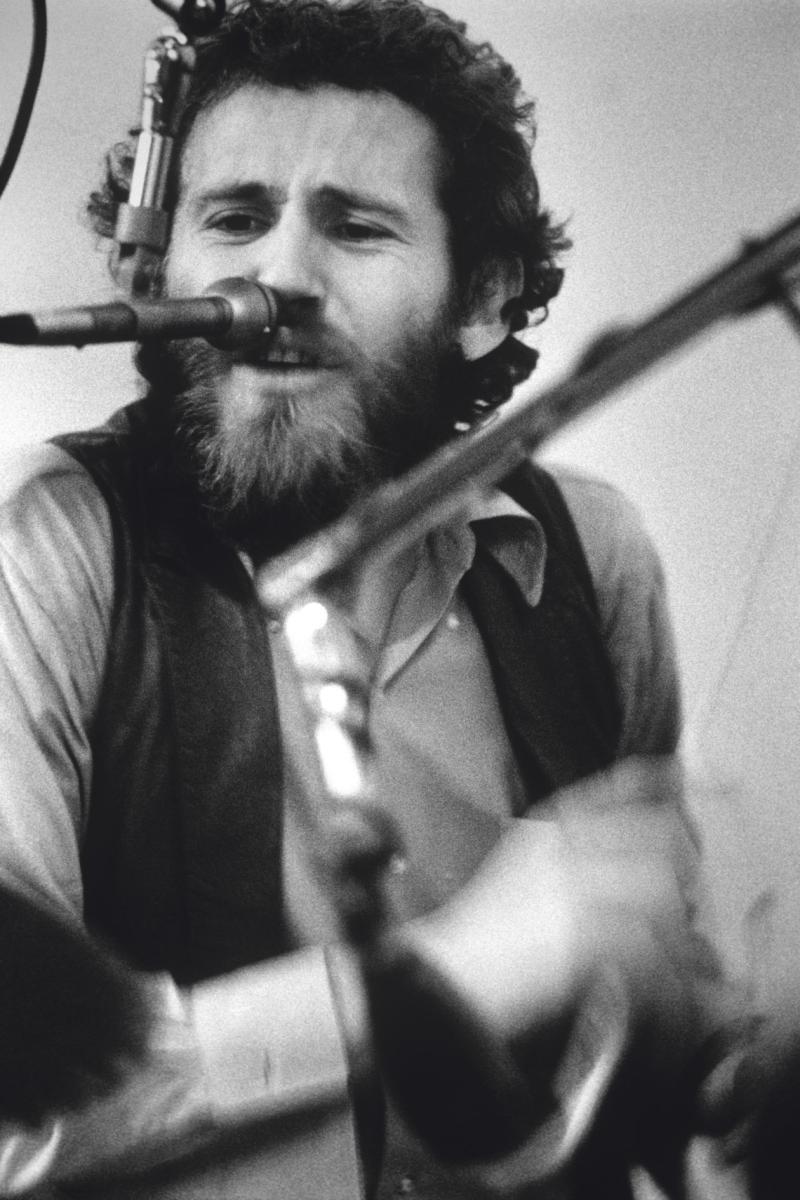

Musicians came and went in the Hawks, and by the time they were in Canada, where the nucleus formed of what would be The Band, they left their leader, who had seen it coming. "They were too musical for me," Ms. Tooze cites Mr. Hawkins as saying. "They got too good." Helm, who was never flamboyant, played his entire kit as though it were any other instrument in the band, muffling his snare with cloth or tape, striking the cymbal sparingly. He liked to vary the tempo within a song; he thought different aspects of a song might call for different tempos. Some people think of a drummer as a sort of metronome, but, he said, "I don't think that's what music should do." He was unassuming about his place in the group as well. If another member's turn at the drums sounded better than his, says Ms. Tooze, "Levon cheerfully picked up a guitar or mandolin."

Ronnie Hawkins had been a stickler for discipline, fining band members for using alcohol or drugs or having girlfriends around, and he made sure they rehearsed constantly, often in the early morning. ("He worked your ass off," Helm said.) The group had learned to work blues and jazz techniques into their playing, so it's hardly surprising that the players eventually came to the attention of another musician who wanted to change his sound and was on the lookout for just the right group to back him.

In 1965, Bob Dylan was ready to electrify. As an acoustic soloist, he didn't really know how to play with a band, but he and the Hawks worked the kinks out and started to tour, only to be met with widespread fury. Except in the South, where Mr. Dylan hadn't been enshrined as a folk purist, his fans booed and threw pennies. Mr. Dylan's response was to turn up the volume, but the band wasn't used to such abuse. When Helm had had enough, he packed his bag one night and took the next bus back to Arkansas.

The drummer eventually rejoined what had become simply The Band and settled into a long, fruitful period of woodshedding that yielded many recordings, including "The Weight" and "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," the two songs that assured the group's fame. The rest of his journey was one of resurrection and triumph, punctuated by the usual snares strewn in a rocker's path: drugs, infighting among band members, the illness and premature decline that seem to stem from the abuses of the road.

There was a bitter and never-to-be-resolved dispute over songwriting credits. Robbie Robertson, The Band's most businesslike member, brought to the table the two elements for which credit is assigned by publishing houses, a song's music and its lyrics. Once in the studio, however, Helm and the other abundantly gifted members (Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson) would make significant contributions to a given song's arrangement. Arrangements aren't credited, though, and as a result most of the songs the Band recorded are attributed to Robertson, meaning most of the money the group made went to one person. After a point, Levon and Robbie never spoke to each other again, though Mr. Robertson visited his former friend in the hospital as Helm lay unconscious just before he died of cancer on April 19, 2012.

Ms. Tooze, a drummer herself, interviewed Helm in 1996 for her Muddy Waters biography. She draws on that material as well as on rigorous research and numerous other interviews with key figures to depict Levon Helm both as a consummate musician and somebody it'd be a lot of fun to have a beer or three with. Helm co-wrote (with Stephen Davis) his own memoir, "This Wheel's on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of The Band" (1993). It, too, is a top read, but Ms. Tooze relates two things the drummer wouldn't, or couldn't, easily convey: the cradle-to-grave sweetness of his personality (with the occasional flare of red-hot anger, to be sure) and the subtle, understated nature of a technique that influences drummers to this day.

Levon Helm's music sprang from a world where often people didn't have shoes or enough to eat at night. But thanks in part to him and the talented gents who played with him, when you say, "Alexa, play Americana," you can still hear echoes of that music's origins, of folks singing on a cabin porch, perched next to a kid beating out a hambone on thighs and chest or tapping on a makeshift drum or, if they didn't have that, on no drum at all.

—Mr. Kirby is the author of "Little Richard: The Birth of Rock 'n' Roll."