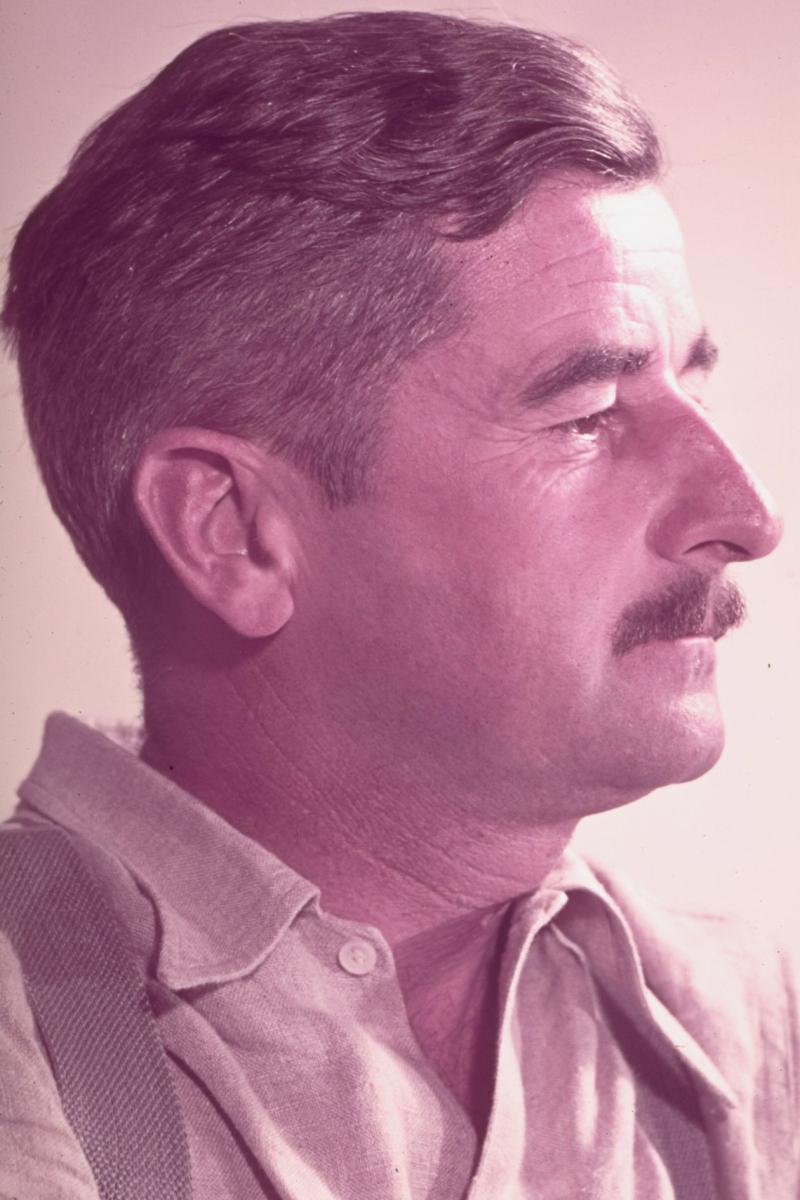

'The Saddest Words' Review: William Faulkner in Black & White

By: Randall Fuller (WSJ)

I became an English professor because once, when I was 17, I opened a battered copy of William Faulkner’s “Absalom, Absalom!” and read the first sentence over and over: “From a little after two oclock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Coldfield still called the office because her father had called it that,” it begins, but then goes on in sinuous and majestic fashion. I thought of that moment recently as I read Michael Gorra’s powerful book, “The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War,” a work animated by an urgent, if irresolvable, question: Should we consider the novelist in our current period of racial reckoning through the lens of his sometimes repulsive racial attitudes, or should we study solely the fiction he created, fiction in which characters both black and white illuminate race relations in this country, fiction that portrays these relations with more nuance than almost any comparable work from the first half of the 20th century?

As the question suggests, Mr. Gorra, a professor at Smith College, is not interested in the Civil War in the same ways that (say) military or political historians might be. While he provides portraits of key figures (Ulysses S. Grant, Frederick Douglass, Nathan Bedford Forrest) and synopses of notable battles (Antietam, Gettysburg), the author is more concerned with what he calls the “forever war over the place of black people in American society, and of slavery in American history”—a “forever war” that continues to roil our nation through its recent debates over Confederate statues and its protests over systemic inequality.

With the exception of a single novel, “The Unvanquished” (1938), William Faulkner wrote surprisingly little about the war. References to the conflict are scattered throughout the novels and stories that depict his fictional Yoknapatawpha County—the “postage stamp of native soil” that he cultivated and tilled for three decades—but these references are vague and often as not inaccurate, representing perhaps folk knowledge rather than established fact.

From another vantage point, however, the Civil War is all-pervasive in Faulkner’s work—a haunting presence that shapes the world he writes about and the very themes, style, and structure of his most memorable work. The war’s root causes of race and slavery, as well as the traumatic defeat that desolated so much of the white South, are determinative forces that shape his characters’ actions and thought. (Quentin Compson in “The Sound and the Fury” and Joe Christmas in “Light in August” are only two of the more prominent examples of protagonists whose lives might be understood as formed, decades after the war, by the conflict and its aftermath.) The experience of traumatic defeat structures nearly every aspect of Faulkner’s narratives, with their recursive, circularly obsessive plots, and their insistence, as he put it in his most resonant phrase, that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Mr. Gorra demonstrates convincingly that this unshakable past for Faulkner came increasingly to involve race. Throughout the 1930s and into the early ’40s, his novels and stories grapple more and more with the legacy of slavery and the reality of Jim Crow. Slavery is typically portrayed in Faulkner’s fiction as a Greek tragedy, an agonized drama in which rape, incest and illegitimate offspring end up deforming or destroying a family. Written during the same period when that supremely romanticized portrait of the antebellum South, “Gone with the Wind,” was one of the most popular books and films in the nation, Faulkner’s work provides unflinching testimony about the corrosive effects slavery had on all strata of his society.

But the novelist’s portrait of his contemporary society gives Mr. Gorra pause. Faulkner was never comfortable as a public figure, and his begrudging interviews, which usually included questions about race relations, reveal why. Although he genuinely detested racial inequality and spoke out against the mob violence that marred his native state (Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi in 1955), Faulkner was also a moderate who worried that desegregation, if enacted too quickly, would lead to social chaos.

Faulkner’s gradualism, representative of his time and place, nevertheless strikes contemporary readers as appallingly shortsighted. And that is not the worst of it. In a Depression-era interview, he asserted that African-Americans had been materially better off in their former condition of enslavement. And in an especially egregious—and drunken—interview the year after the Till lynching, he made an unconscionable statement when asked about the possibility of federal troops returning once again to the South to ensure the integration of its public schools: “If it came to fighting I’d fight for Mississippi against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes.”

Mr. Gorra does not try to defend the indefensible. But he also refuses to reflexively “cancel” Faulkner—to jettison Faulkner from the American canon because of his attitudes. Instead, the critic offers a reason to continue reading the novelist that will strike readers as either generous or misguided. Faulkner the private citizen was, like most of us, a reflection of his society; but once he began to write, Mr. Gorra suggests, something surprising happened. In order to create convincing fiction, it was necessary for him to imaginatively become each of his characters, to enact what Henry James once called the novelist’s imperative of “trying to see the other side as well as his own, to feel what his adversary feels, and to present his view of the case.”

Mr. Gorra believes that when writing, Faulkner was able to suspend his prejudices and even to dramatize and to feel those prejudices as they impinged upon others. “He could stand outside . . . ideology only by first assigning it to a character,” Mr. Gorra writes. “He inhabited those beliefs by inhabiting another person. Then he saw them clearly, and in that act he became better than he was.” This faith in the power of fiction raises some other questions, however. If writing enabled Faulkner to become a better person, at least while writing, why did this process fail to affect the rest of his life? And to what extent should we make claims for literature as a transformative force in a world in which systemic injustice can continue unabated?

But Mr. Gorra is after something different here. “Stories become legacies,” he writes, referring to the way the South consoled itself with the fiction of a “Lost Cause” after its defeat. Faulkner’s corpus may not always counter this dishonest story. But if we read Faulkner’s fiction in the context of his life, we may better understand our own possibilities and our limits, the way the present is always burdened by the past, and ultimately just how difficult it is to become better than we are. For Mr. Gorra, Faulkner’s fiction should be read these days for “the drama and struggle and paradox and power of his attempt to work through our history, to wrestle or rescue it into meaning.” Reading Faulkner today we discover just how much imagination and courage can be required to face the past.