The billion-dollar question: How does the Clipper mission get to Europa?

ars technica : At one end of the conference room, four large window panes framed a view of the San Gabriel Mountains. Outside, ribbons of greenery snaked across the hills, a vestige of spring before the dry summer season descends upon Los Angeles.

Inside, deep in discussion, a dozen men and women sat around a long, oval-shaped wooden conference table. They were debating how best to send a daring mission, known as Europa Clipper, to Jupiter’s mysterious, icy moon Europa. Although hundreds of scientists and engineers were already planning and designing this spacecraft, the key decisions were being made in this room on the top floor of the administrative building at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The politics of getting to Europa are anything but straightforward.

The politics of getting to Europa are anything but straightforward.

NASA

It will not be cheap or easy to reach Europa, which lies within the complicated gravitational tangle of Jupiter and its dozens of moons, 600 million kilometers from Earth. But the payoff, scientists feel, is potentially incalculable. Beneath Europa’s ice, perhaps just a few kilometers down in some areas, lies the most vast ocean known to humans. With abundant energy emanating from the moon’s interior into the ocean, scientists speculate life might exist—probably just microbes, but why not something krill-like, too?

In recent years, scientists have locked down a set of nine scientific instruments to fly on the Europa Clipper probe, which will look, search, and sniff for signs of life during 47 flybys that will skim to within 25 kilometers of the moon's surface. But one big question remains, and it will probably determine whether the mission costs in the range of $2 billion or $3 billion dollars: how best to get the six-ton probe from Earth to the Jupiter system?

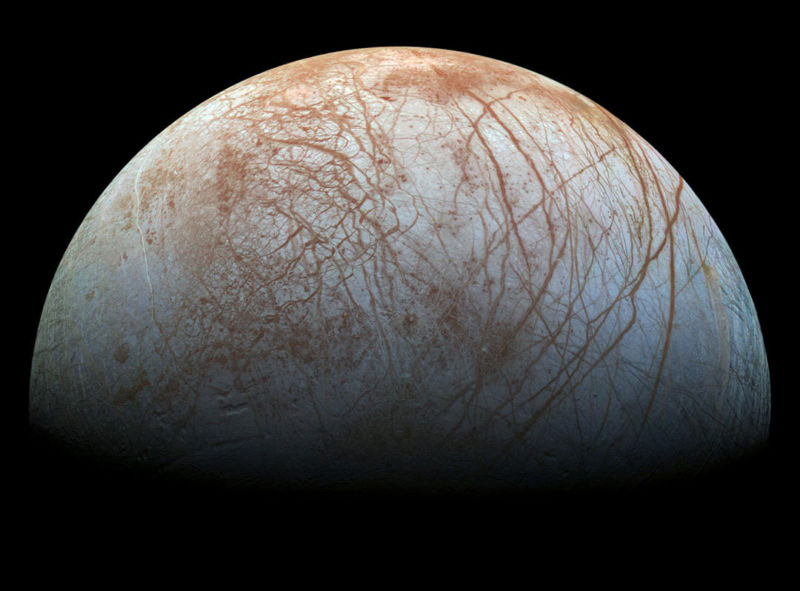

Why send the Clipper, shown here, to Europa? Because the Galileo mission to Jupiter

Why send the Clipper, shown here, to Europa? Because the Galileo mission to Jupiter

in the 1990s and early 2000s raised a host of questions about this moon.

NASA

This was a key reason for the meeting held in early April outside the San Gabriel Mountains. Barry Goldstein, who is managing the ambitious Europa Clipper mission at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, stood at the head of the conference table. “There’s been a lot of discussion about launch vehicles,” he said. “So we’ve prepared a chart.”

The physics of that chart displayed the capability of commercially available, lower-cost rockets to throw the Clipper to Jupiter; it also highlighted the capability of NASA’s more expensive Space Launch System. The latter rocket is more powerful than any booster flying today, but it has never launched, and when the titanic rocket will be ready for the launchpad is not certain.

Reaching Europa relies on more than physics, and invariably politics matter more when it comes to missions bound for the outer planets. This kind of exploration requires years of planning and development, as well as years of flight. In addition to costing billions of dollars, such missions must be managed across multiple presidential administrations and the comings and goings of Congress.

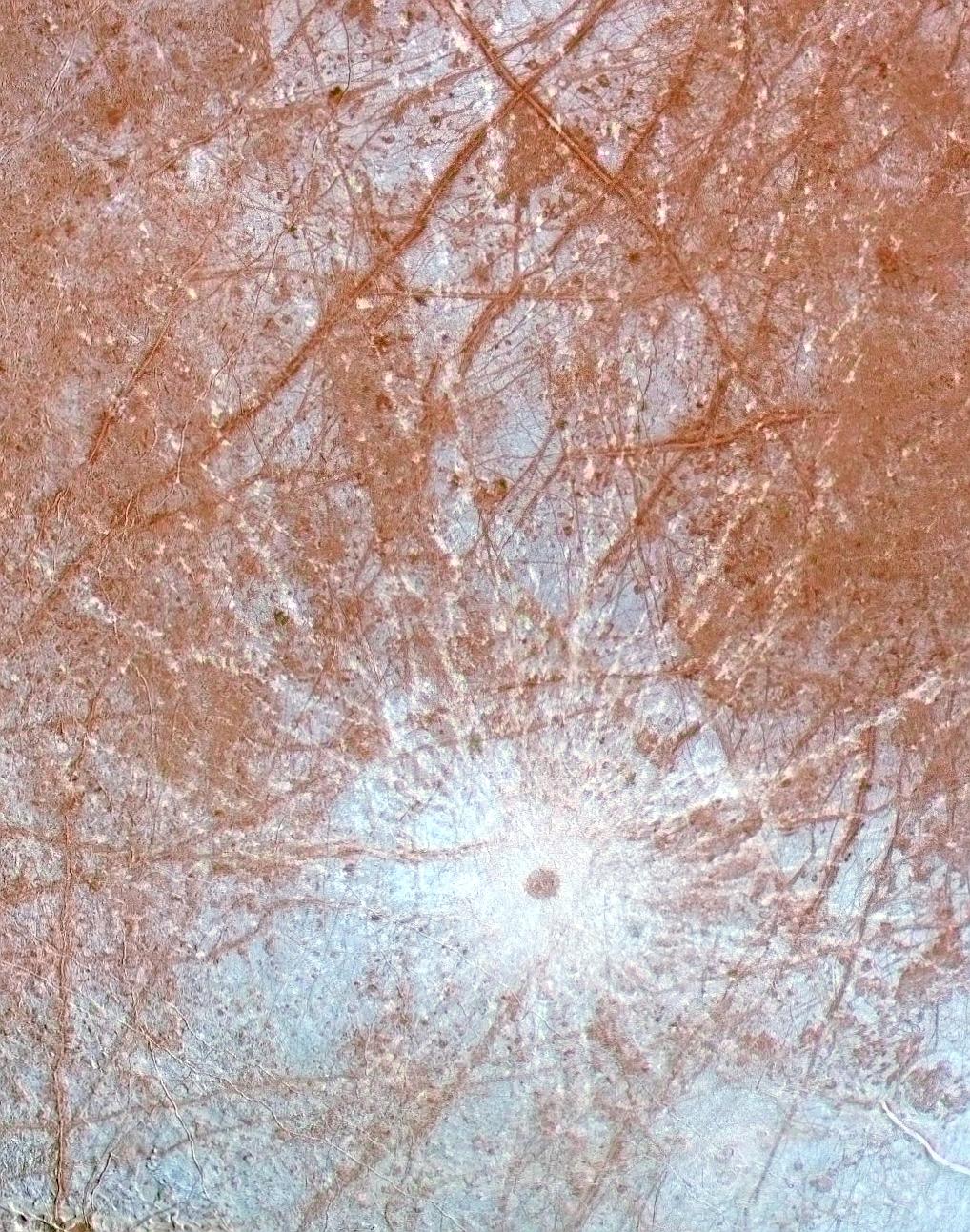

This enhanced color image shows the region surrounding the young impact crater Pwyll,

This enhanced color image shows the region surrounding the young impact crater Pwyll,

a 26km diameter impact crater thought to be one of the youngest features on the surface of Europa.

The diameter of the central dark spot, ejecta blasted from beneath Europa's surface,

is approximately 40km, and bright white rays extend for over a thousand kilometers

in all directions from the impact site. These rays cross over many different terrain types,

indicating that they are younger than anything they cross.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

For Europa, one Congressman matters more than all the rest. Since 2004, John Culberson has been on a quest to make a Europa mission happen. In the just-completed budget for fiscal year 2018, the Texas Republican pushed funding for planetary science missions to its highest-ever level, more than $2 billion. And of that, he had funneled $495 million to this NASA facility for Europa exploration.

So before the discussion of launch vehicles began, Goldstein had something he wanted to tell the politician who had flown in from Houston. “On behalf of the entire project, let me start with this,” Goldstein said. “Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you. And I could go on for what, 60 minutes? We are in really good shape.”

Is Block 1 ready?

In a white dress shirt, sans tie, Culberson shook off the compliment. First elected to Congress in 2001, he started agitating for a Europa mission only a few years later during the presidency of George W. Bush. The White House wasn’t having it. At the time, an already cash-strapped NASA was shoveling every spare dollar into the Constellation Program for human exploration, which would ultimately go nowhere.

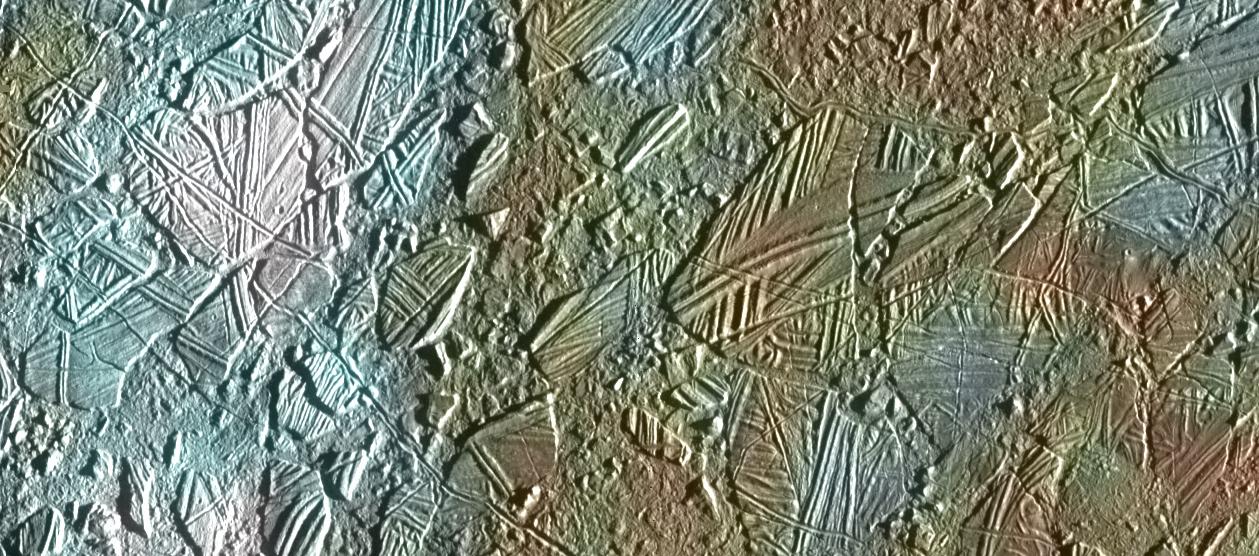

View of a small region of the thin, disrupted ice crust in the Conamara region

View of a small region of the thin, disrupted ice crust in the Conamara region

showing the interplay of surface color with ice structures.

The white and blue colors outline areas that have been blanketed by a fine dust of ice particles

ejected at the time of formation of the large crater Pwyll some 1,000km to the south.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

By the time Barack Obama won his second term in the White House, Culberson’s seniority and membership on the House Committee on Appropriations allowed him to begin providing limited funding for a Europa mission. (Scientists have long had Europa atop their wish-list, but NASA leadership had been hesitant to take on such an ambitious, costly program). At the end of Obama’s presidency, Culberson had risen to chair of the Appropriations subcommittee that sets NASA’s budget, and the Europa Clipper had become an official NASA program.

Culberson loves space. He views planetary exploration and the potential for finding life elsewhere in the Solar System as the most enduring legacy he can leave behind for humanity. Since last summer, however, Culberson has focused on securing funding for victims of Hurricane Harvey, which dropped four feet of rain on Houston and ranks with Hurricane Katrina as the costliest storm to ever hit the United States. Some of his own family members had only just moved out of a trailer back into renovated housing. But on this Friday, he had come to California to see how the Clipper mission was doing, as well as a follow-on mission to land on Europa.

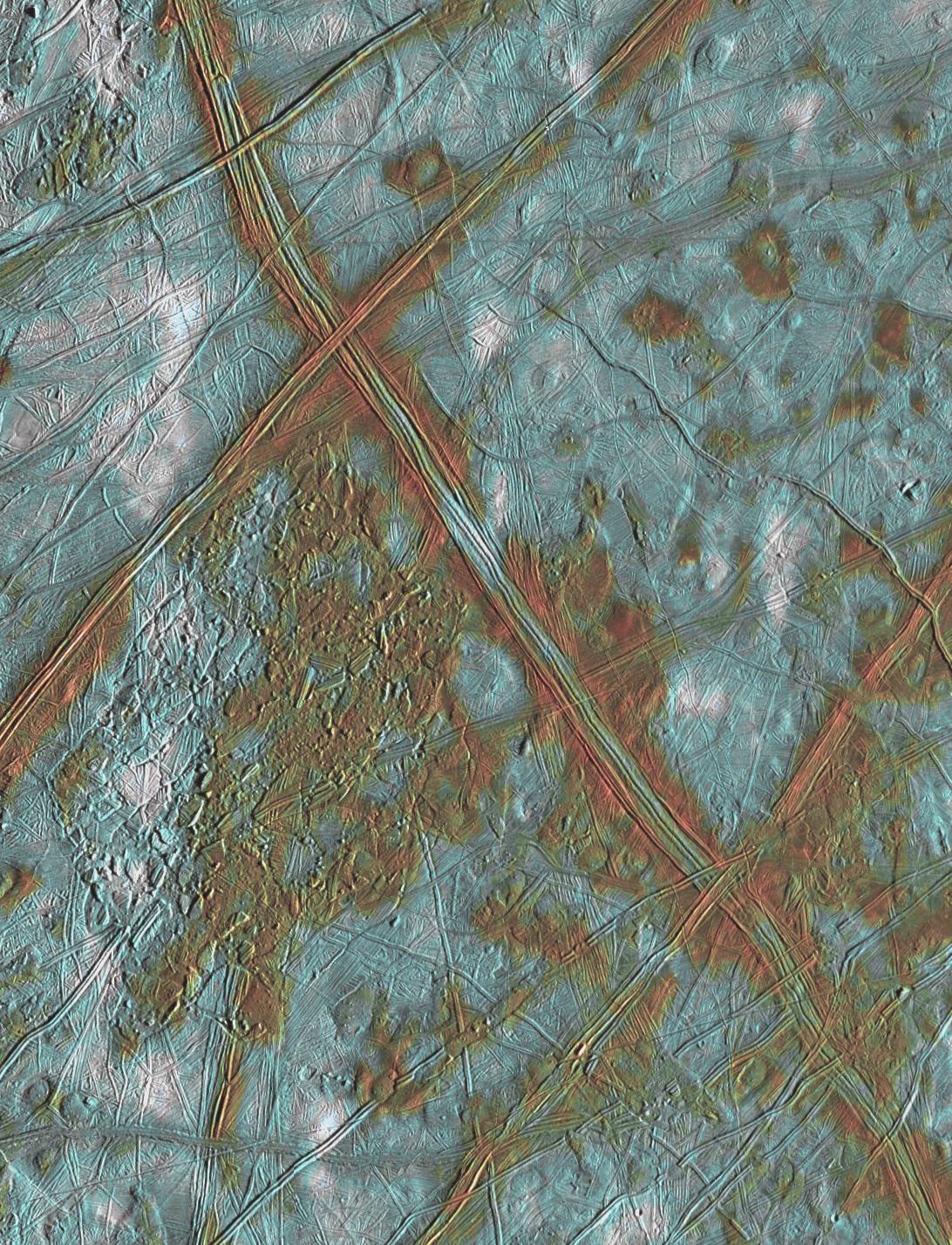

This synthetic color image shows three distinct spectral units. The bright white areas are ejecta rays

This synthetic color image shows three distinct spectral units. The bright white areas are ejecta rays

from the relatively young crater Pwyll, located about 1,000km to the south.

Also visible are reddish areas that can be seen along the ridges in the region of disrupted terrain

in the center of the image and near the dome-like features where the surface may have been thermally altered.

Thus, areas associated with internal geologic activity appear reddish.

The third distinct color unit is bright blue and corresponds to the relatively old icy plains.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

The missions are coming along nicely, but soon critical decisions about how to get Clipper to Jupiter must be made. The JPL scientists and engineers want to send the Clipper, which is so big that its solar panels have a wingspan as long as a basketball court from end to end, directly to Jupiter. They prefer this because a quicker trip to Jupiter will require less thermal protection, and, more importantly, they want the Clipper to reach Jupiter before the follow-on mission designed to land on and sample the moon’s icy surface. Ideally, the Clipper will scout Europa for several years and identify the most interesting, safest landing location.

A direct shot of a six-ton satellite to Jupiter requires a rocket with a lot of muscle. During the briefing, Culberson was told no commercial rocket can do this, even SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, which flew for the first time in February. (It is not clear whether NASA specifically asked SpaceX about the Falcon Heavy and Europa, as Goldstein said figures for all the commercial rockets were provided by a competitor to SpaceX, United Launch Alliance.) In the charts shown in the JPL conference room, engineers had modeled a Falcon Heavy with a small “kick stage,” but they had not considered alternatives, such as a Falcon Heavy with a more powerful Centaur upper stage for a direct-to-Jupiter mission.

A close-up of Thera and Thrace, two reddish regions that disrupt the older icy ridged plains.

A close-up of Thera and Thrace, two reddish regions that disrupt the older icy ridged plains.

Thera (left) is about 70km wide by 85km high and appears to lie slightly below the level of the surrounding plains.

Thrace is longer, shows a hummocky texture, and appears to stand at or slightly above the older surrounding bright plains. One model for the formation of these and other chaos regions on Europa is complete melt-through of Europa's icy shell from an ocean below.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Because the existing commercial rockets were not powerful enough, Goldstein said only NASA’s Space Launch System could get Clipper directly to Jupiter. The first version of this rocket, Block 1, can put 70 tons into low Earth orbit, and its Interim Cryogenic Propulsion upper stage has enough oomph to reach Jupiter in about three years. This is half the time of the commercial rockets, which will require more time to slingshot around inner Solar System planets to attain a Jupiter trajectory.

What Culberson really wanted to know is whether the big NASA rocket will be ready for a second launch in June 2022. This is a good question. Congress has patiently funded the SLS rocket’s development since 2011 and now spends more than $2 billion annually to fund work to design and build it. Even so, the SLS remains at least two years away from the launchpad for its maiden test flight. A few lawmakers have begun to ask questions about why it is taking so long.

Meanwhile, the engineers in California have told the Texas congressman that the Europa spacecraft can be ready for launch in just four years, thanks to his generous funding. Especially important, money has been front-loaded to arrive earlier in the project when development costs are highest.

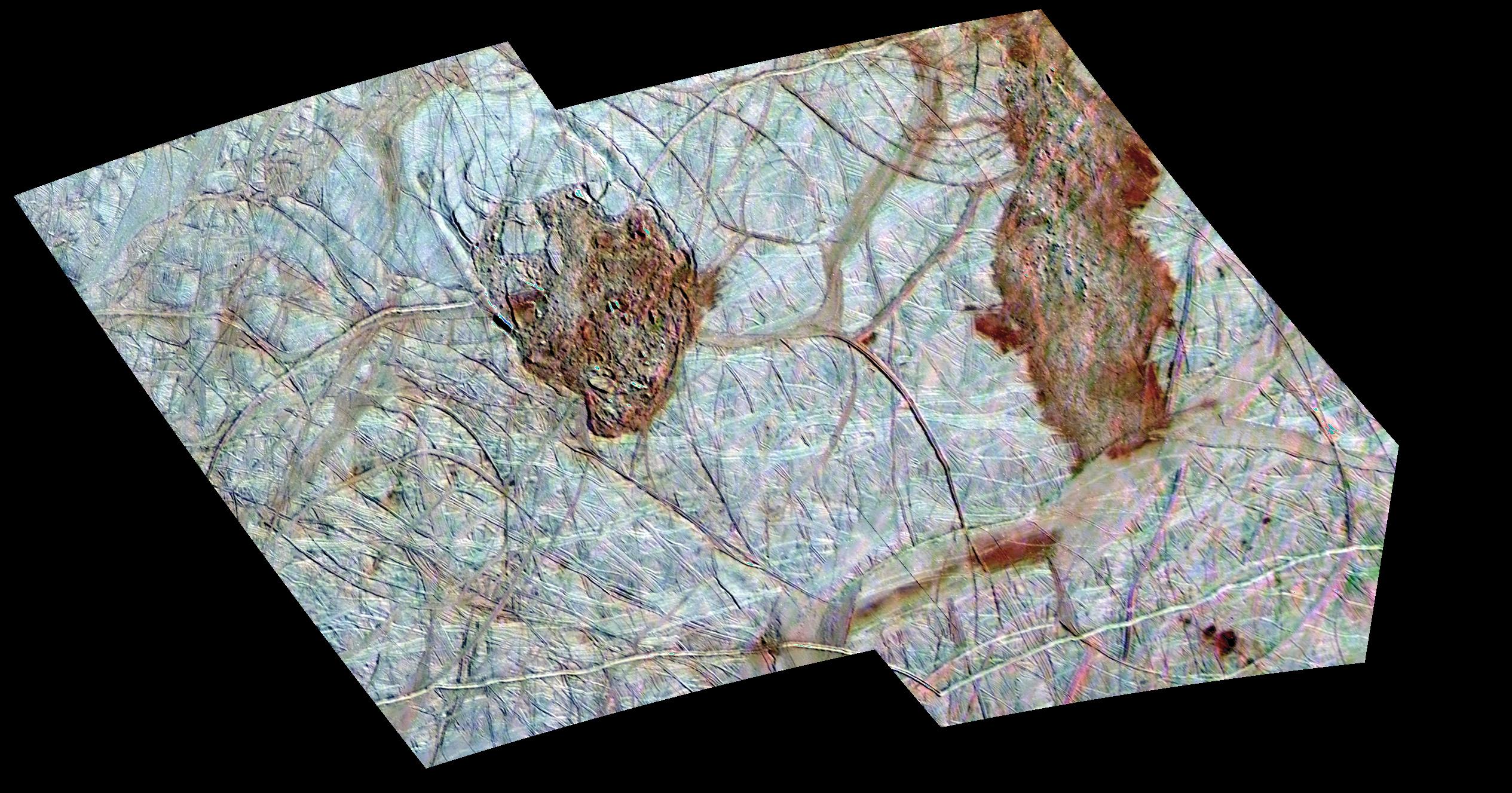

This image compares the size of Europa's ice rafts

This image compares the size of Europa's ice rafts

with a similarly scaled photo of the California Bay Area.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

If the spacecraft will be ready by mid-2022, Culberson wanted to make sure the booster was ready, too. “Block 1 is on time and on target?” he asked. “I want to make sure the SLS Block 1 is the rocket you need, and it’s on time.”

Congress and the White House

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory traces its roots to the 1930s, when students from the California Institute of Technology in nearby Pasadena headed north into the San Gabriel Mountains to experiment with rockets. The US Army later used the area for rocket tests, but the country eventually decided to base its rocket propulsion development at a military base in Northern Alabama where the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and his team ended up after World War II. This would become Marshall Space Flight Center, where NASA designed the Saturn V and space shuttle rockets.

With other NASA centers focused on human spaceflight, JPL became the go-to place for robotic exploration, spearheading famed missions such as the Voyagers, Galileo, and Cassini spacecraft. Because of this, Goldstein deferred on Culberson’s question, saying that he could only relate what the rocket scientists at Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama were telling him.

“From everything we’ve seen, it is on time,” Goldstein said of the SLS rocket. “The big thing that was in the funding bill this year, a second mobile launcher, makes that very viable from the point of view of the SLS manifest.”

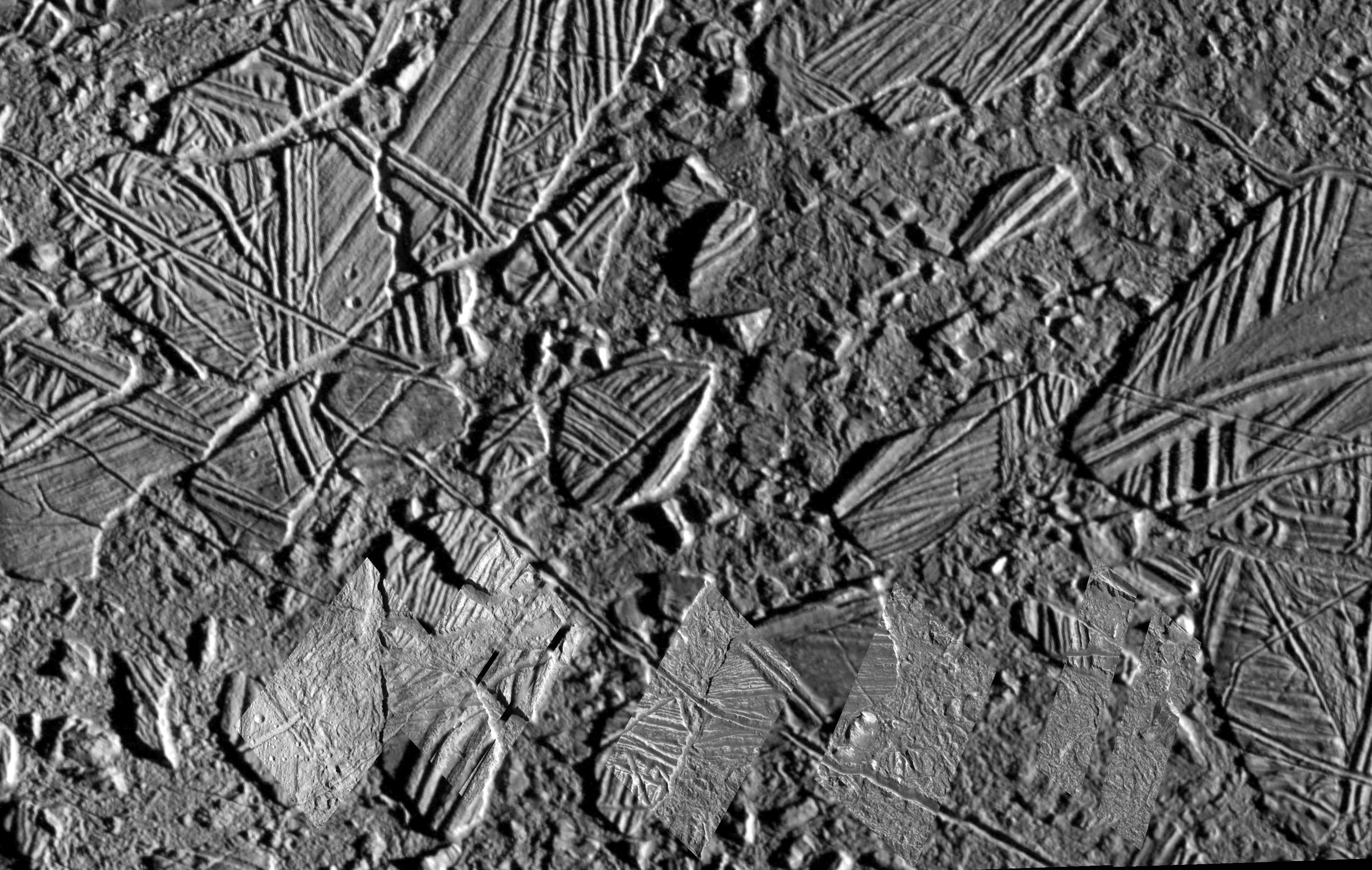

This mosaic of the Conamara Chaos region clearly indicates relatively recent resurfacing of Europa's surface.

This mosaic of the Conamara Chaos region clearly indicates relatively recent resurfacing of Europa's surface.

Irregularly shaped blocks of water ice were formed by the breakup and movement of the existing crust.

The blocks were shifted, rotated, and even tipped and partially submerged within a mobile material

that was either liquid water, warm mobile ice, or an ice-and-water slush.

The presence of young fractures cutting through this region indicates that the surface froze again into solid, brittle ice.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Culberson interjected, “I did that personally.”

Indeed, he had. This large structure had been one of the biggest impediments to getting the Europa Clipper mission off the launchpad in 2022 aboard an SLS rocket. The large “mobile launcher” tower supports the testing and servicing of the massive SLS rocket, as well as moving it to the launchpad and providing a platform from which it will launch. Between the first test flight and second flight of the rocket, NASA intends to upgrade the SLS rocket’s upper stage to give it more kick in sending larger payloads deeper into the Solar System. This larger and longer upper stage, known as the “Exploration Upper Stage,” will necessitate significant changes to the mobile launcher. The agency estimated it would take 33 months to accomplish this work, creating a nearly three-year delay expected between the first and second flights of SLS.

Not only was this lengthy delay embarrassing for NASA, which wants desperately to show that the SLS can be a useful tool in its exploration plans, it was also bad news for the Clipper. The probe would have had to wait for at least the second or even third launch of the SLS rocket to get its ride into space. This would necessarily push the Clipper's launch into the mid-2020s.

NASA had a solution for this problem, but it came at a cost. It could build a second mobile launcher at Kennedy Space Center for the larger version of the SLS rocket while keeping the original tower in its Block 1 configuration for the Clipper launch. Culberson accepted this deal, tucking an additional $350 million into the fiscal year 2018 budget to build a second launch tower.

“I’m very pleased by that,” Goldstein replied to Culberson.

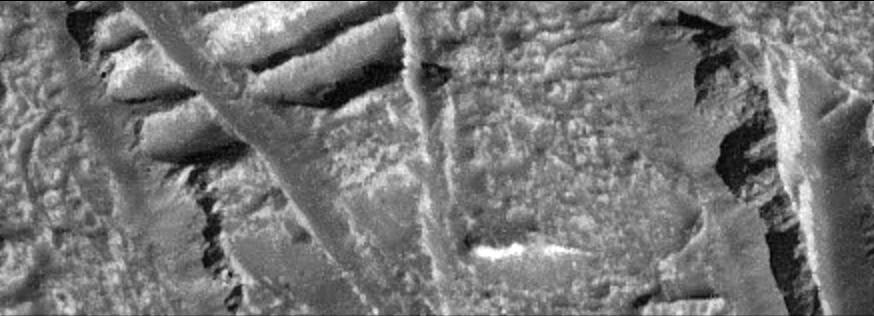

This view of the Conamara Chaos region shows cliffs along the edges of high-standing ice plates.

This view of the Conamara Chaos region shows cliffs along the edges of high-standing ice plates.

The washboard texture of the older terrain has been broken into plates that are separated

by material with a jumbled texture. The cliffs themselves are rough and broadly scalloped,

and smooth debris shed from the cliff faces is piled along the base.

The height of the cliffs and size of the scalloped indentations

are comparable to the famous cliff face of Mount Rushmore.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

At this moment, a tall physicist on the other side of the conference room table joined the conversation. As the long-tenured and widely respected director of NASA’s planetary exploration program, James Green balances a multibillion budget and prioritizes how best to use NASA’s resources to explore the Solar System with robotic probes. As a member of NASA’s administration, he also works for the White House, not Congress. (Days after the California meeting, NASA announced it had promoted Green to a position as the agency’s chief scientist. He will retain considerable oversight of the Europa mission in this role.)

The Trump administration has taken a different view of the Europa mission. While it nominally supports the exploration of Jupiter’s icy moon, the budget-writers in the Office of Management and Budget think Culberson’s plans for the Clipper and follow-on lander mission cost too much.

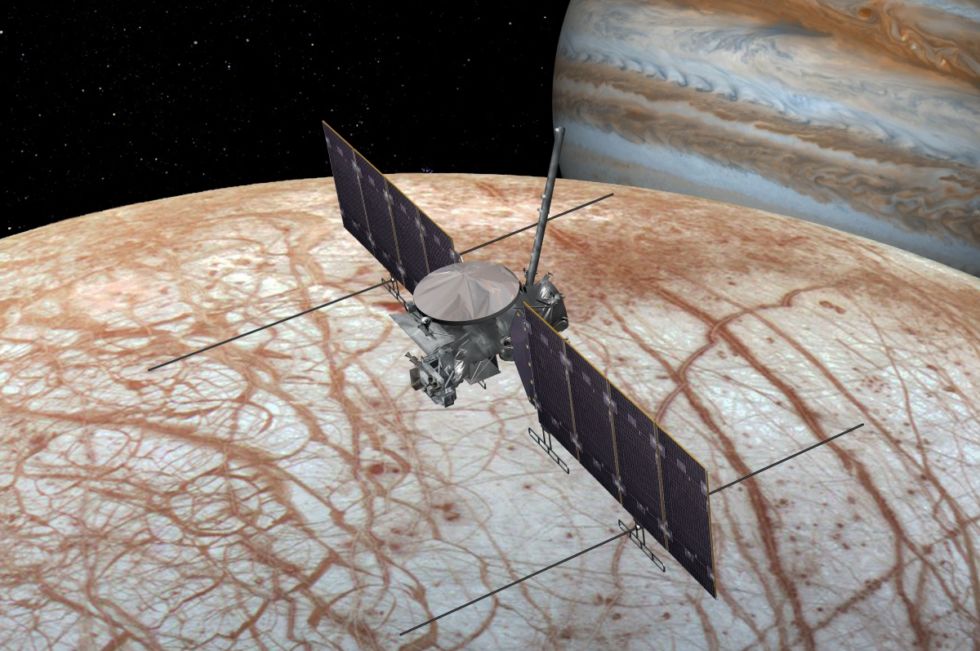

US Rep. John Culberson (R-Tex.) holds a prototype antenna for the Europa landing mission.

US Rep. John Culberson (R-Tex.) holds a prototype antenna for the Europa landing mission.

In the background, at center, is NASA’s Jim Green.

NASA

One way they want to save money is by launching the Clipper on one of the commercial rockets (known as an EELV, or an Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle) dismissed by Goldstein. Such a rocket would cost on the order of $100 to $200 million, compared to the estimated $1 billion cost of an SLS rocket launch. The White House also prefers not to push the schedule.

“This is the reality of my world,” Green said, entering the discussion for the first time. “The administration says that 2025 would be the launch date for Clipper. And, while the budget we received keeps it on a 2022 timescale, the administration says that we must launch on an EELV. We will not be able to use the SLS.”

Culberson cut Green off here. “The chances of that are zero,” he said.

During the Obama administration, from his Appropriations position in the House, Culberson summarily ignored the White House budget requests for NASA. Now, with a Republican in the office, he is less dismissive—but only slightly so. In setting the 2018 budget and in negotiations for the 2019 NASA budget, Culberson had already reached a deal with Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.) for an SLS launch of the Clipper.

“I can guarantee that the full committee chairman in the Senate will be thrilled with what we have discussed,” Culberson said.

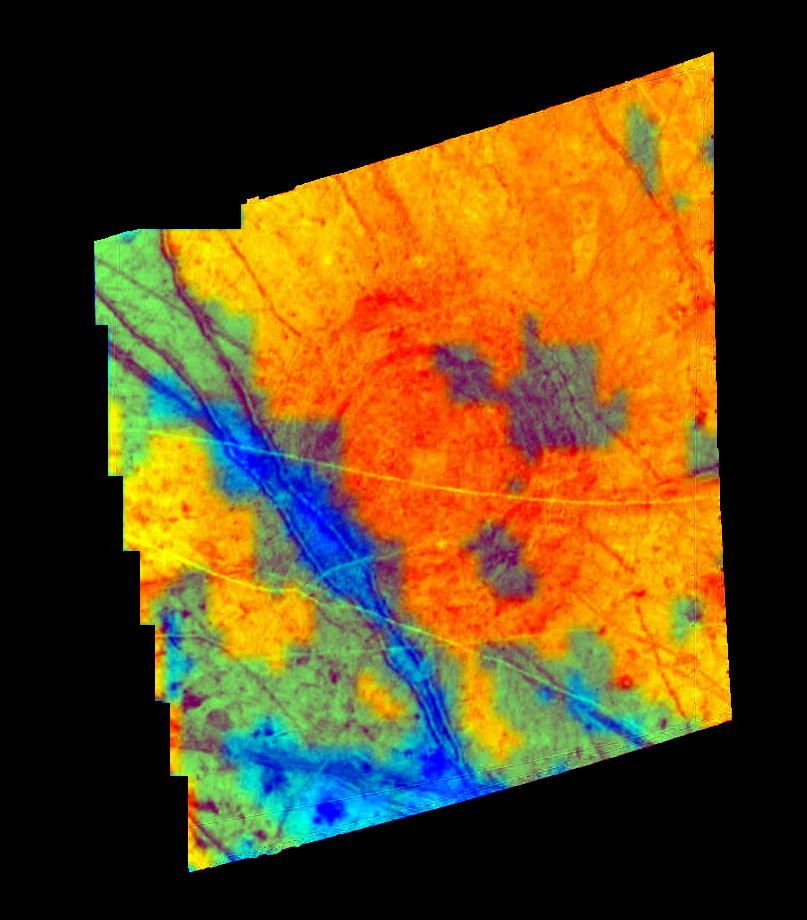

This composite image shows the distribution of ice and minerals for the structure named Tyre,

This composite image shows the distribution of ice and minerals for the structure named Tyre,

the largest and likely one of the oldest on the moon.

Tyre, at 140km diameter, is the size of the Island of Hawaii and thought to be the site

where an asteroid or comet impacted Europa's ice crust.

The blue in this image indicates areas with higher concentrations of mineral salts.

These salts are similar in composition to those found in the bottom of Death Valley, California.

The yellow-orange regions are areas that have a high surface abundance of water ice.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

“Fantastic,” Green said. “But indeed, in my world, in supporting the administration and the administration’s position, I wanted you to know that that was what was delivered to Congress. That’s what I have to plan against.”

Political deals

It is perhaps not much of a stretch to say that one Congressman’s embrace of exploring Europa—which indeed is undiscovered country and as worthy a place to send a probe as any in the Solar System—is profoundly changing much of the country’s civil spaceflight efforts.

To get large planetary science budgets through the Senate, Rep. Culberson needs Sen. Shelby’s support. The Alabama senator is perhaps most well-known nationally for his last-minute opposition in 2017 to Republican Roy Moore’s candidacy in the Senate runoff last year. (Moore lost to Democrat Doug Jones in the deep-red state.) But behind the scenes, Shelby is probably the most important voice for space policy on Capitol Hill. That position only solidified this month after he became chairman of the entire Senate Appropriations Committee.

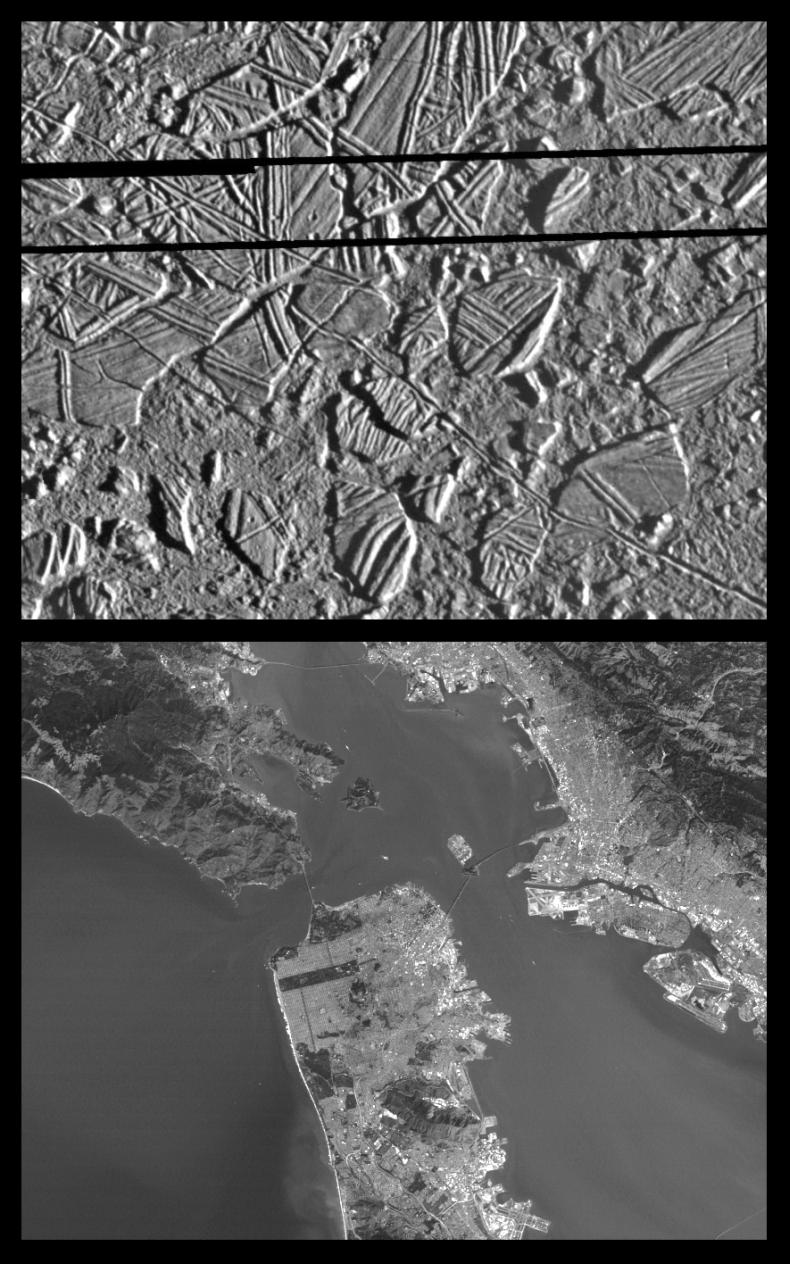

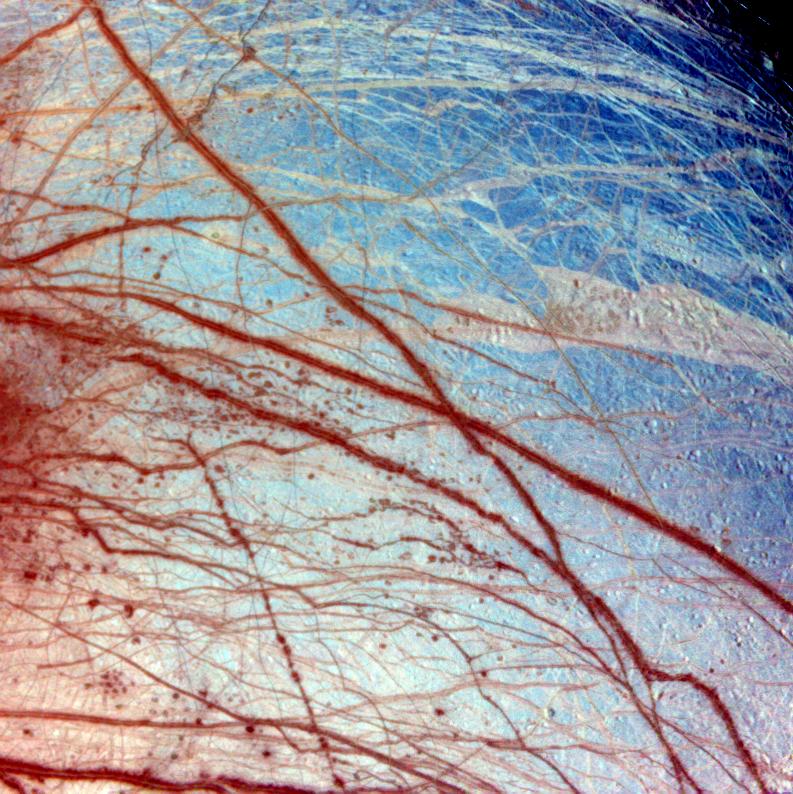

False color has been used here to enhance the visibility of certain features of the Minos Linea region.

False color has been used here to enhance the visibility of certain features of the Minos Linea region.

Triple bands, lineae, and mottled terrains appear in brown and reddish hues,

indicating the presence of contaminants in the ice.

The icy plains, shown here in bluish hues, subdivide into units with different albedos

at infrared wavelengths probably because of differences in the grain size of the ice.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

What Shelby wants, more than anything, is funding—more than $2 billion a year—for SLS development. NASA has been working on this titanic rocket since 2011, and its slow development process suits Shelby fine because his home state’s NASA facility, Marshall Space Flight Center, manages the program. The political deal is pretty transparent: Shelby gets big money for the SLS. Culberson gets big money for planetary science. With the Clipper, the SLS rocket gets a high-profile mission, and the scientists get spacecraft to Jupiter faster. For Congress and the scientists, the extra money for an SLS launch seems of little consequence.

It is not clear whether the Trump administration will upset these carefully laid plans. The president’s budget, notably, did not include funding for a second mobile launcher. But thanks to Culberson, the final Congressional bill did include it, and Trump, however unhappily due to a lack of funding for a border wall, signed the funding measure anyway.

The fight over a launch vehicle, on the other hand, remains in progress. A final decision isn’t absolutely necessary for a year or so, but at some point, NASA will have to pick a commercial rocket or the SLS. If the agency doesn’t pick the SLS rocket, then the handshake agreement between Culberson and Shelby might fall apart.

This is the highest-resolution image of Europa at 6m per picture element.

This is the highest-resolution image of Europa at 6m per picture element.

The image was taken at a highly oblique angle, providing a vantage point similar

to that of someone looking out an airplane window, albeit 500km high.

The features at the bottom of the image are much closer to the viewer than those at the top of the image.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

On top of all that, the 2018 midterm elections could reshuffle this calculus further. Shelby, who turns 84 next month, was reelected in 2016. Culberson’s position is a bit more perilous.

Several times he joked during the meeting in California about the seven Democrats running for his Congressional seat in west Houston, noting that they had painted him as an anti-science candidate. The world-class scientists in the room laughed at this, and justifiably so, as Culberson nerdily debated the finer points of mass spectrometry or magnetometry with them. They appreciate Culberson for his funding but also for his earnest interest in their scientific findings.

The west Houston seat Culberson has held since 2001 has been reliably red, but in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton narrowly won his district. Democrats have therefore marked the 7th District as a pick-up opportunity, and there is a non-trivial chance the incumbent will lose. And even should Culberson win, the House may very well flip into Democratic control.

Outwardly, at least, Culberson shrugged off these concerns. But he must know that seeing the US House flip to the Democrats would, at the very least, probably slow down the Clipper mission. Losing his seat would probably not only slow down the mission into the mid-2020s; it would also certainly imperil the ambitious but expensive lander mission now scheduled for launch in 2025, or later. (On an SLS rocket, of course).

Missions that cost billions of dollars—even those that could potentially find life on another world for the very first time in human history—need passionate champions in Congress. It seems safe to say that more than a few California scientists, who might otherwise vote Democratic, will be closely watching Houston-area election results this fall in hopes that a conservative Republican will emerge as the victor.

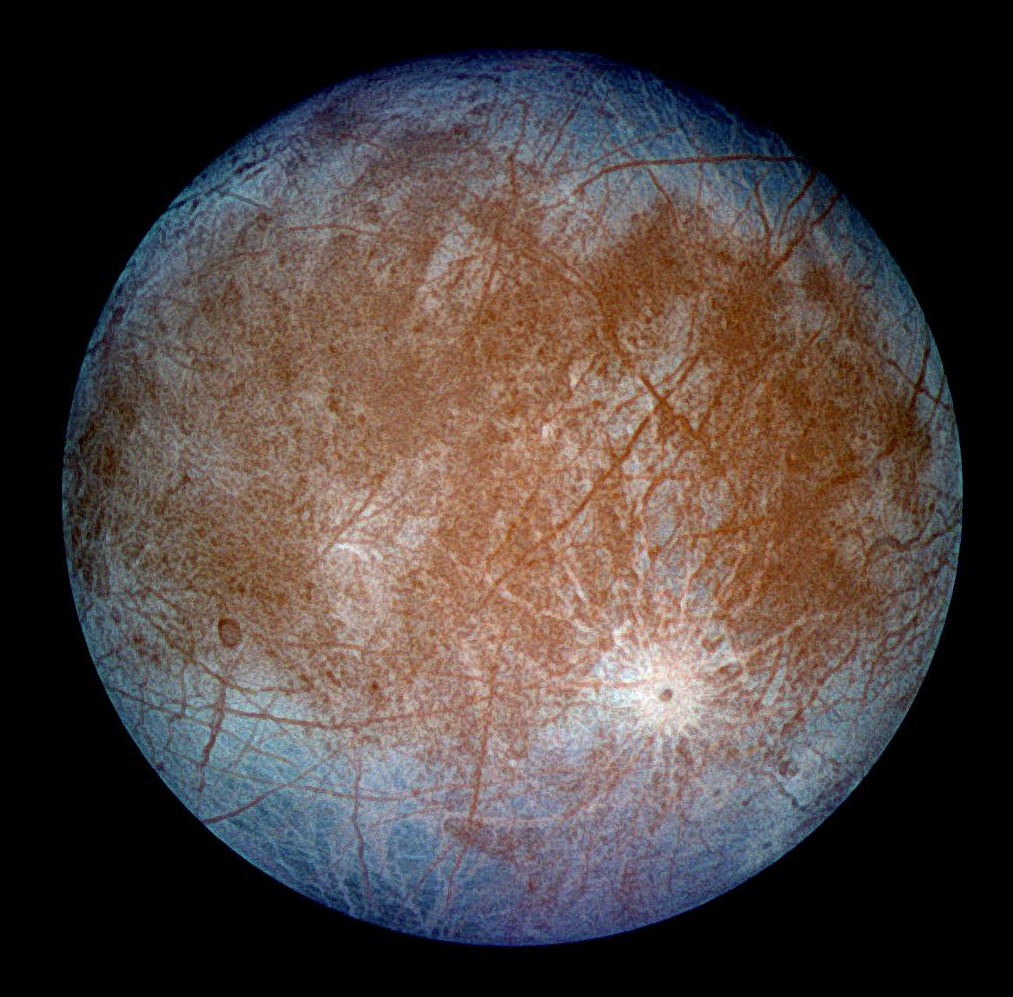

A false-color composite image of Europa.

A false-color composite image of Europa.

NASA/JPL/DLR

=============================

by Eric Berger

There may be links in the Original Article that have not been reproduced here.

A fascinating look at the intersection of science and politics.

And best of all... Europa!!

Dear Friend Bob Nelson: About getting to Europa.

Perhaps a planetary private public series of partnerships will address both the political will and the costs involved in this exciting opportunity.

The payouts to the private sector from space research developed technologies and their commercial applications is well documented.

If seen as an investment primarily in resource discovery and usage, as well as new technological developments and the profit opportunities they bring will get this done.

The win win may be the best way to sell this venture.

No one will argue the value of knowledge for its own sake.

Getting anyone to fund the bills is quite another matter.

The sizzle point that works probably must be based on self interest.

Peace and Abundant Blessings.

Enoch.

Interesting article.

No good guys, no bad guys... differing approaches...

The real world!